There have been few geniuses throughout history quite as iconic as Sherlock Holmes. After all, Einstein may have come up with two new theories of relativity, but he never came back from the dead a er plunging hundreds of metres in a final fight with his evil arch-nemesis. In fact, it’s unclear whether Einstein even had an evil arch-nemesis, putting him at a disadvantage to Holmes right o the bat.

The detective’s legendary brilliance has inspired countless adaptations over the years, spanning fi lm, TV, comic books, radio and even board games. He’s turned up in songs, in video games; he’s even blessed the English language with new turns of phrase such as “elementary, my dear Watson” and “no shit, Sherlock.” His only real shortcoming is that he is, of course, fictional, and therefore disqualified from true geniushood by virtue of not actually existing.

You’d think, though, that if there were one person capable of matching such a character, it would be his creator. Shouldn’t the person who came up with that mind be even more impressive? Why don’t we use ‘Arthur Conan Doyle’ as a shorthand for mental prowess?

Well, it’s not that complex, honestly: he just wasn’t that smart. Not how Holmes is, at any rate—not cool and calculating and oh-so-sceptical. Because Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle is most famous today for two things: creating one of the greatest logical and scientific thinkers in the history of literature, and publicly claiming that fairies existed after falling for an embarrassingly obvious prank pulled by two random schoolgirls.

Now, despite the image you probably have in your mind of a man with the middle name Ignatius, Doyle came from surprisingly humble beginnings—his childhood was honestly more Shameless than Sherlock. Born into poverty in 1859, and with a cripplingly alcoholic father, Doyle and his eight siblings spent many of their formative years separated out across Edinburgh, relying on friends and family to help them get by.

Nevertheless, Arthur spent seven years at an expensive boarding school, which just goes to show that you don’t need to be born to rich parents to achieve your dreams as long as you have a handful of wealthy uncles willing to pay for you to attend fancy private schools away from your destitute father instead.

It’s fair to say he fucking hated his time there—Victorian English boarding schools have never been known for too much love and kindness—and outside of his twin pursuits of writing to his mum and playing cricket, he spent his time there resenting his bigoted peers and getting regularly beaten up by his teachers as part of a ritual known at the time as “education.”

“Perhaps it was good for me that the times were hard, for I was wild, full blooded and a trifle reckless. But the situation called for energy and application so that one was bound to try to meet it,” he would later write about the experience—and, in any case, he added, “my mother had been so splendid that I could not fail her.”

Now 16, and A Man, he went home to Edinburgh, where his first task was to sign the papers to have his dad sectioned, just in case you thought that traumatic childhood had ended at graduation.

It was finally time for Arthur Doyle to make his own way in the world—so he decided to apply for medical school. It was a decision that must have surprised his family. There are plenty of what’s called “hereditary occupations” out there, even today—fishing is a big one, as are things like joining the military or working in some legal field. Basically, if your parents have one of those jobs, you’re statistically way more likely to go that way yourself.

For the Doyles, it was Art. Arthur’s father had been an artist—and actually, he still was, producing some increasingly bizarre stuff from his cell in Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum—and so had been his father’s father, John Doyle. Neither had been particularly good or successful, if we’re honest, but if there’s one thing the Victorians knew, it was that tradition trumps common sense every day, and so, by rights, Arthur ought to have gone into drawing too.

Instead, he wanted to be a doctor. Inspired not by family, but by a student his mother was renting a room to—once again, I feel like I should point out just how divorced his dad was from the rest of the family—he applied to the University of Edinburgh to study medicine. It was an auspicious decision.

If Arthur had decided anything else—a different university, or a different course, or even just delayed his application by a couple of years—then we likely wouldn’t have one of the most recognizable and successful fictional characters known to literature today. I mean, hell—he might have actually been a doctor for a living, and what a loss that would have been to the world.

See, it was at the University of Edinburgh that Conan Doyle, now newly if subtly renamed, met his muse: a man named Joseph Bell. He was one of Conan Doyle’s lecturers, and a surgeon by profession, but that wasn’t what made him famous. His party trick, if you can use that term for a mid-lecture demonstration, was to visually dissect a patient’s life and circumstances based on their clothing, demeanor, accent and so on, and I’m sure that sounds familiar to anybody who’s read or seen or heard of Sherlock Holmes, because it’s exactly what he does too.

By the end of his first year as a physician, he had earned so little that his tax return was literally rejected for being suspiciously low—it was returned to him with a note reading “most unsatisfactory.”“Dr Bell would sit in a receiving room, with a face like a [Native American, but in a term that a Victorian English dude would use, if you know what I mean], and diagnose people as they came in, before they even opened their mouths,” Conan Doyle once told an interviewer of his inspirational teacher. “He would tell them their symptoms, and even gave them details of their past life, and hardly ever would make a mistake.”

Compare that with his hero Holmes’s appraisal of a woman who “had plush upon her sleeves, which is a most useful material for showing traces. The double line a little above the wrist, where the typewritist presses against the table, was beautifully defined … observing the dint of a pince-nez at either side of her nose, I ventured a remark upon short sight and typewriting, which seemed to surprise her.”

And: “she had written a note before leaving home but a er being fully dressed … both glove and finger were stained with violet ink. She had written in a hurry and dipped her pen too deep. It must have been this morning, or the mark would not remain clear upon the finger. All this is amusing, though rather elementary, but I must go back to business, Watson.”

In fact, Holmes ended up being such a blatant rip-off of Conan Doyle’s old lecturer that when his old university friend, Robert Louis Stevenson—who was also a novelist rather than a scientific man, which might make a person wonder exactly what was going wrong in the university’s STEM departments at the time—first read the character he felt compelled to write to Conan Doyle to ask “can this be my old friend Joe Bell?”

But, of course, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The Arthur Conan Doyle who was studying medicine under Bell had dipped his toe into the waters of fiction, but he was still only writing short stories for magazines—and he still intended on becoming a doctor in the end.

And so, after graduating from Edinburgh, Conan Doyle didn’t head to a publisher or a literary agent; instead, he moved to the south coast of England with the equivalent of about £1,000 total to his name, and set up a medical practice.

It was here that he began his lifelong habit of failing, hard, at literally almost everything he tried. For weeks he had no patients at all—and when someone eventually did knock at his door, it wasn’t a customer but a debt collector.

‘Through the glass panel I observed that it was a respectable-looking bearded individual with a top-hat,” he later wrote in The Stark Monro Letters, a work of “fiction” that was, in reality, more like a diary that just had all the names and places changed.

“It was a patient. It MUST be a patient!” he wrote. “[I] waved him into the consulting-room … He seated himself at my invitation and gave a husky cough.”

Showing the kind of deductive genius that would eventually make him famous, Conan Doyle immediately diagnosed the visitor with a bronchial problem, and that probably would have been quite impressive had the man not in fact simply been sent by the gas company to collect on a bill—one that wasn’t even Conan Doyle’s to begin with.

“You’ll laugh … but it was no laughing matter to me. He wanted eight and sixpence on account of something that the last tenant either had or had not done. Otherwise the company would remove the gas-meter,” Doyle wrote. “How little he could have guessed that the alternative he was presenting to me was either to pay away more than half my capital, or to give up cooking my food!”

And genuine customers, when they did finally turn up, sometimes couldn’t pay him enough to cover his own costs—as he wryly complained in a letter to a family friend, “if I got more patients I would have to sell the furniture.” By the end of his first year as a physician, he had earned so little that his tax return was literally rejected for being suspiciously low—it was returned to him with a note reading “most unsatisfactory.” Conan Doyle, of course, sent it straight back with his own note attached: “I entirely agree.”

Conan Doyle was a resourceful man, however, and knew he could be more than just an unsuccessful physician. Throughout his life, he tried his hand at many career paths, becoming at various times an unsuccessful soldier (too fat to enlist), an unsuccessful MP (too unpopular to get elected), an unsuccessful ophthalmologist (literally never managed to attract a single patient to his practice), and an unsuccessful celebrity cricketer (his team, the—sigh—the Allahakbarries, was founded by J.M. Barrie, counted among its players Rudyard Kipling, H.G. Wells, P.G. Wodehouse, G.K. Chesterton, Jerome K. Jerome, A.A. Milne, Walter Raleigh, and a whole heap of other dudes responsible for half the Classics section in Waterstones, and was really, really bad at cricket.)

But medicine, the army, politics and sport’s loss was literature’s gain, and rather than having to spend his time treating Victorian eyeballs or shooting impertinent foreigners, Conan Doyle was able to devote himself instead to writing stories about an antisocial junkie with a bizarre name and an affinity for deductive reasoning. His name, for some reason, was Sherlock Holmes.

But we’re not here to talk about that. We’re going to concentrate on the other things Conan Doyle spent his time doing. Like trying to talk to ghosts.

Séances, mediums, spirit possession—Conan Doyle believed in it all. He’s even the guy who came up with that whole “Curse of Tutankhamun” thing we were all scared of as kids. In fact, he called spiritualism “the most important thing in the world,” and he spent the equivalent of millions of pounds trying to prove its veracity. He was a member of the Ghost Club and the Society for Psychical Research, and travelled the world to promote his belief in the paranormal—frequently falling out quite publicly with other notable figures of the day.

Take Houdini, for example—probably Conan Doyle’s most famous nemesis in the spiritualist world. The two first met in 1920, both at the height of their respective celebrity, and while they started out as friends, brought together by a shared interest in investigating the supernatural, the relationship soon turned sour.

Kind of ironically, given Conan Doyle’s reputation as the architect of critical thinking and Houdini’s as … well, Houdini, the guy whose name is as tied to superhuman trickery as Holmes’s is to deductive reasoning, it was Houdini who was the rational one of the pair—he clocked that the séances weren’t legit after the pair attended one that claimed to be channeling his mum.

She apparently wrote him a long letter in perfect English, signed with a cross, which was such an odd choice for a Jewish woman who only spoke Hungarian that Houdini figured it must have been fake. But Conan Doyle? He was taken in completely by various people claiming to be able to speak to the dead, over and over again.

Now, we shouldn’t think he was a willing fool in this; he actually spent a reasonable amount of time and energy trying to debunk spiritualism before he was convinced, which honestly just makes it worse. He would frequently declare brazen frauds to be the real magical deal, including some that were specifically designed to show him how easy it was to fake those spiritualist feats he believed in so devoutly.

So, for example, there was William S. Marriott—or, when he was on stage, the magical Dr. Wilmar. When he wasn’t performing stage magic, he was acting as a sort of proto-Derren Brown or James Randi, going around duplicating the claims of so-called psychics and mediums and making damn sure people knew how he—and not some dead rando with too much spare time on their hands—did it.

In December 1921, he invited Conan Doyle and three witnesses to a photo session in which he took a few snaps of the writer. Everyone attested there was no chicanery involved, it was a perfectly normal camera, and everything was above board and extremely not suspicious.

But when the photos were developed, there was a ghostly translucent figure behind Conan Doyle. It was nothing he hadn’t seen before—the only difference was that, this time, the photographer wasn’t pretending the images were kosher. They were published in the Sunday Express, along with witness statements as to the apparently normal photo and development process and an explanation from Marriott as to how fake the images were, which is to say, 100 percent fake.

So Conan Doyle put out a statement of his own, so that everyone would know how totally Not Mad he was. “Mr Marriott has clearly proved a point that a trained conjurer can, under close inspection of three critical pairs of eyes put a false impression upon a plate. We must unreservedly admit it,” he wrote, before claiming that, actually, he had known Marriott was a fake all along because he had the wrong hands to be a real medium.

It’s no wonder Conan Doyle missed the more subtle clues that the photos were fake, such as the fact that the fairies were all obviously two-dimensional, and also fairly blatant copies of illustrations from a popular children’s book of the time, or, lest we forget, mythical creatures.“A conjurer has certain physical characteristics,” he wrote, including “long, nervous artistic fingers.” Real spirit-talkers, he said, had hands that were “short, thick and work stained,” and so even if he might be taken in by Dopey, Doc or Sneezy, he wasn’t going to be fooled by old lady-fingers Marriott over here.

Now, some people may consider such a reaction to be “petty” or “embarrassing,” but it’s actually remarkably sober compared to some of the other times he got caught out. The reason Houdini was such a sceptic towards the whole spiritualism schtick was largely because he’d been in Vaudeville basically his entire life, and he knew only too well how easy it was to fool a willing audience.

When he tried to explain this to Conan Doyle, he was met with denial. And not just like “well, sure you can replicate it, but these guys did it for real” kind of denial—Conan Doyle straight-up told Houdini he was lying about not being a magical being with powers granted to him from beyond the veil. Which, when you’ve spent your whole life putting in the mental and physical effort to perfect your stage act, isn’t actually that nice a thing to hear.

The same was true of the “Masked Medium,” a woman seemingly able to conjure ghostly spirits to tell her the contents of a locked box filled with personal items brought by audience members, which certainly makes the afterlife sound like a pretty boring gig. But she got every single personal item right, in detail, and Conan Doyle was won over.

The problem was, the woman wasn’t a psychic or a medium or a spirit channeler—she was just a tech nerd. That “mask”—a veil, in fact, which the performer never took off—hid not just her face but a small wireless radio, with an assistant on the other end listing o the items in the box. The “ghost” she had summoned had been an extra, waving a gauze sheet around in the dark. So when Conan Doyle heard that the act had come clean, and weren’t psychics at all but psychic debunkers, he had quite the cognitive dissonance going on.

So what did he do? The same thing he had with Houdini: he told everyone that the Masked Medium was psychic, and that her explanation for how the trick had been done was a lie, and that even if it wasn’t a lie that didn’t mean it hadn’t been real when he saw it. “There is nothing to show that the first séance was not genuine,” he protested.

And yet none of this even comes close to Conan Doyle’s greatest claim to credulous fame. That came in 1920, after he first heard about a series of photographs taken by two young girls—cousins, aged 16 and nine, from the village of Cottingley, West Yorkshire. The “Cottingley fairies,” as they’re now known for fairly obvious reasons, is one of the most notorious hoaxes in history—if only because it’s so unbelievably daft. It was essentially a photoshop job: the two girls, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, had produced five photos that they said showed proof of fairies. Yes, as in Tinkerbell.

It was most likely an innocent prank that got out of control. After all, doctoring photos of themselves to include things like fairies, or unicorns, or Transformers, or silly things like that—that’s the kind of thing any kid might do. But, unfortunately, their mum moved in the same kind of circles as Conan Doyle, and that meant she was about as gullible as he was too. She sent the photos to a bunch of spiritualist magazines, saying they were the real deal, and, suddenly, the kids were famous.

But they likely wouldn’t have become so famous, had the creator of the most popular literary character in history not taken up their cause. Conan Doyle took to the national press, writing a long article in The Strand magazine titled “Fairies Photographed—An Epoch Making Event Described by A. Conan Doyle,” in which he called the images “the most astounding photographs ever published.”

“It seems to me that with fuller knowledge and with fresh means of vision, these people”—by which he means fairies, just to be clear—”are destined to become just as solid and real as the Eskimos,” he wrote, Victorianly.

“These little folk who appear to be our neighbors, with only some small difference of vibration to separate us, will become familiar. The thought of them, even when unseen, will add charm to every brook and valley and give romantic interest to every country walk.”

Now to be fair to Conan Doyle, he did carry out what was, in his mind, a thorough investigation into the authenticity of the photos.

Unfortunately, this being a hundred years ago, the definition of “thorough investigation” was somewhat looser, and consisted mostly of Conan Doyle saying things like “two working-class girls wouldn’t be able to fool me!” and “yes, OK, their house is full of paintings they’ve done of fairies but I just don’t think they painted these ones, OK?”

Faced with such compelling evidence, it’s no wonder Conan Doyle missed the more subtle clues that the photos were fake, such as the fact that the fairies were all obviously two-dimensional, and also fairly blatant copies of illustrations from a popular children’s book of the time, or, lest we forget, mythical creatures.

Even at the time, there were people pointing out how odd it was that the fairies all seemed to be dressed in the latest French fashions, and how despite being the creators of what at least one popular mystery novel writer claimed would ‘mark an epoch in human thought’, the girls didn’t seem all that interested by the appearance of fairies in front of their face.

“For the true explanation of these fairy photographs what is wanted is not a knowledge of occult phenomena but a knowledge of children,” read Truth, a newspaper from Sydney, while the novelist Maurice Hewlett wrote that “knowing children, and knowing that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has legs, I decide that [the girls] have pulled one of them,” which is basically just an old-timey way of saying “you’ve been had, Conan Doyle.”

Conan Doyle was undaunted. He had, he pointed out, taken the photos to various technical experts in companies like Kodak and Ilford, and the majority had said they were real. This was a rather optimistic claim on his part, as the experts had mostly said things like ‘these photos are fake’ or “well, they probably weren’t faked in a lab, but that doesn’t mean they’re proof of fairies existing, you get that, right, Arthur?,” but we should give him his dues here: some people were even more credulous. The novelist Henry de Vere Stacpoole, for example, said the photos were real because the girls just, you know, looked honest.

“Look at [Frances’s] face. Look at [Elsie’s] face,” he wrote. “There is an extraordinary thing called Truth which has ten million faces and forms—it is God’s currency and the cleverest coiner or forger can’t imitate it.”

Of course, the trouble with loudly proclaiming to the world that you believe in fairies is that the world may well proclaim right back that you’re an idiot, and that’s exactly what happened to Conan Doyle.

Gradually, the world—or, at least, that part of it that believed in fairies—quietly dropped the topic, and started regarding the man who gave them Sherlock Holmes as a bit, well, embarrassing and unhinged. Not that he would have minded too much. He’d have been upset that so much of the world today rejects the idea that ghosts and fairies and spiritualists are among us, but he made it quite clear throughout his life that, if his reputation had to suffer for his belief in Tinkerbell and Smurfs, then so be it. And to illustrate just how far he’d come from “elementary, my dear Watson,” he explained himself thus:

I have always held that people insist too much upon direct proof. What direct proof have we of most of the great facts of Science? … Only the ignorant and inexperienced are in total opposition, and the humblest witness who has really sought the evidence has more weight than they.

In 1930, Conan Doyle finally got the opportunity to penetrate the veil between the living and the dead for himself, which is to say: he died. Despite his insistence that spirits can pass into our world and effect change or send messages, he appears to have slept through Elsie and Frances admitting, more than half a century later, that the photos were indeed fake.

“It was just Elsie and I having a bit of fun,” Frances told the BBC in a 1985 interview. “But just imagine: you’re 16, and messing around with your cousin, and the world’s most famous writer of the world’s most famous incredibly clever guy comes along and publishes your photos for the whole world to see and writes a long tract about how your fun camera experiment is proof positive that fairies exist and the whole world rests on these photos … well, what are you going to do?”

“Two village kids and a brilliant man like Conan Doyle—well, we could only keep quiet,’” explained Elsie. “I can’t understand to this day why they were taken in,” said Frances. “People often say to me, “Don’t you feel ashamed that you have made all these poor people look like fools? They believed in you.’ But I do not, because they wanted to believe.”

Of course, perhaps it wouldn’t have made any difference if Conan Doyle had found out the photos were a fake. After all, he’d probably say, just because those ones were frauds, doesn’t mean fairies don’t exist. The girls probably had the wrong shaped hands to take real photos of fairies.

But you would have to think he’d be disappointed. When he looked at those photos, he didn’t just see two girls sitting next to what are clearly paper cut-outs of fairies—he saw the dawning of a new age.

“When Columbus knelt in prayer upon the edge of America, what prophetic eye saw all that a new continent might do to a effect the destinies of the world?” he wrote in The Strand. “We also seem to be on the edge of a new continent, separated not by oceans but by subtle and surmountable psychic conditions. I look at the prospect with awe … there is a guiding hand in the a airs of man, and we can but trust and follow.”

__________________________________

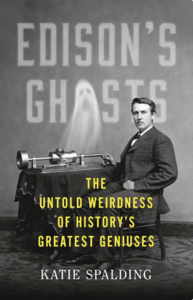

Excerpted from EDISON’S GHOSTS by Katie Spalding. Copyright © 2023 Katie Spalding. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.