In 1701, Copenhagen was a burgeoning city fortress of 60,000, a seaside capital enclosed by canals and high walls with just four gates. The streets were narrow and crowded, lined on each side by cramped, timber-framed buildings, though strewn among the city were architectural jewels. Copenhagen held the Renaissance-style Frederiksborg Palace, symmetrical baroque gardens, and Gothic churches. The University of Copenhagen, the second oldest institute of higher education in Scandinavia, had the Round Tower astronomical observatory where the speed of light was first quantified. The texts held in the university’s library compiled just about everything we knew about the world so far, and somewhere in the bowels of that vast monument to intellectualism was the office of Professor Arni Magnusson.

This particular morning, a letter had arrived for him. From the king.

Arni was a self-made man in Copenhagen, that city of opportunities. He had left his native Iceland at twenty to study divinity. His interest in the gospel stemmed primarily from a love of old scripts rather than religious devotion. He came late to the hobby of manuscript collection. Rival antiquarians had accumulated the largest and most valuable codices, found at churches and official establishments around Europe, and set up workshops where the copying busywork was delegated to assistants. After completing his education, Arni had the edge of knowing Old Norse, the language that had died out everywhere in Scandinavia except isolated Iceland. Denmark, Sweden, and Norway had evolved regional languages over time, influenced by their global position. The Icelandic that Arni learned growing up wasn’t the same dialect as the Icelandic spoken by Snorri Sturluson and the Saga writers, but the versions were closely related enough for the stories to still be readily understood.

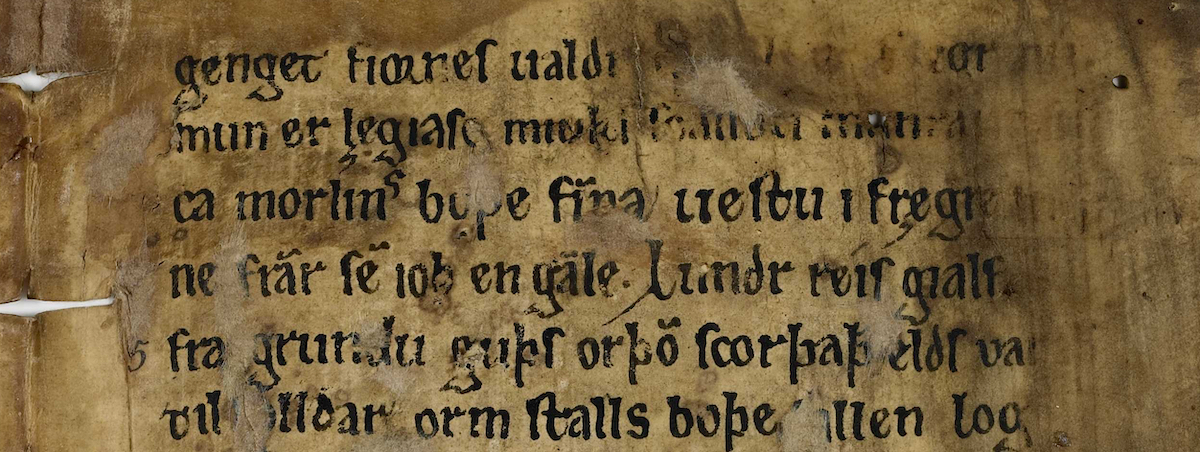

Through his roommate at school, Arni was hired as an assistant to the Danish royal antiquarian to transcribe and translate thousands of pages of Icelandic material; the diligent and detailed work he accomplished in his years of apprenticeship alone would have been enough to demarcate him as a great scholar. His practice of transcribing material word for word, including abbreviations and original spellings, was above and beyond the standards of his times.

“And that is the way of the world,” he wrote early on, confidently explaining his methods. “Some men put erroribus (errors) into circulation, and others afterwards try to eradicate those same erroribus. And from this both sorts of men remain busy.”

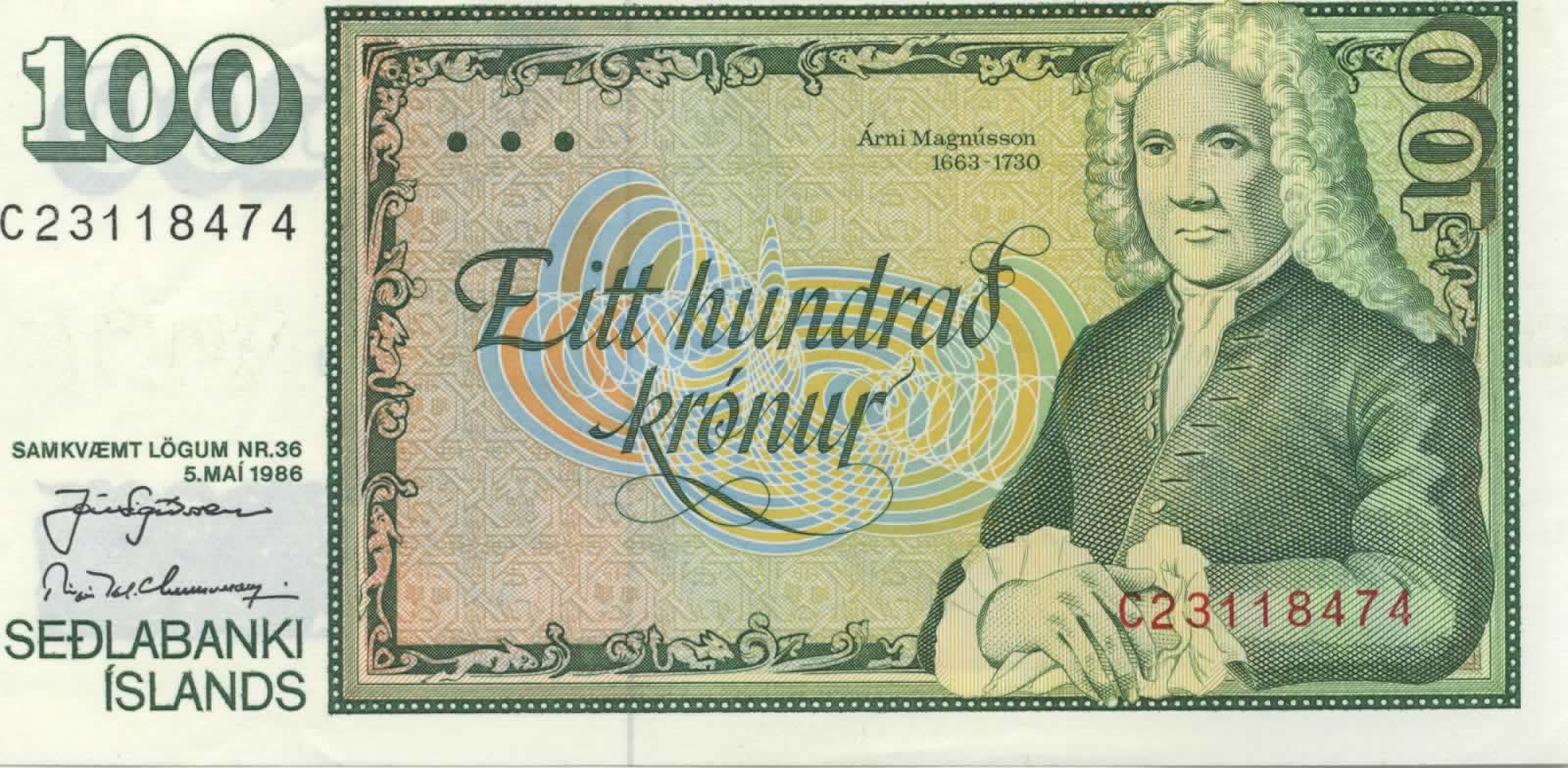

He used multiple copies of the same story to compare them for accuracy, noted where scripts came from, and recorded every peculiar detail about the calligraphy and words written in the margins, whether it was commentary from the writer or notes from previous readers. Two scripts in his collection have child-like stick figures drawn at the bottom by some unknown previous owner, smiling at Árni’s “serious and contemplative” manner and his blue eyes which expressed the “shadow of hidden things in his heart,” as ones colleague later described him. An apparently melancholy and thoughtful man, his sad face is known to every Icelander old enough to have shopped for candy before 1994, as the One-Hundred-Krona-Man. His portrait, which formerly featured on the 100 Krona bill, appeared so sad that he was eventually, after a period of inflation, replaced by a fish.

The royal antiquarian passed away suddenly, at a young age, and Arni was left selling his large collection of vellum and manuscripts. The paper copies had value themselves as text ready for print, and Arni kept most of the Icelandic pieces. He proceeded to work for a Danish statesman, Matthias Moth, whose sister was a mistress to the king. This unconventional proximity to the highest power put Arni in a position to influence Icelandic affairs, including trade deals and political positions. In return for his various favors, he asked to be payed in scripts. He traveled to Germany, Norway, and Sweden to gather scripts form local collectors, some for Danish royal libraries, some for himself. After twenty years of charming the Copenhagen elite, he was finally made professor, with his own chair inside a glorious building, those years of unsteady travel and poor income behind him. What could possibly interrupt such a fine life?

Ah. Right. The letter.

In writing, the king requested Arni to set sail “with the first possible ship” to … Iceland.

No. No, no, no. Arni loved being Icelandic, but he hated Iceland. It was no place for a scholar. Through his political connections, he kept a close eye on Iceland’s current affairs and had only a year earlier described, in a letter to a Norwegian friend, how Iceland had “only the worst of news, sheep widely extinct, people passing away, ravaged by famine, in the immense depth of snow.” That dire situation had only escalated. Europe was under a cold spell, known now as the Little Ice Age, which was felt most acutely at the edge of the continent. Fjords and bays were frozen over, and the coastline facing the Arctic Ocean was blocked by drifting icebergs. Fishing was impossible. Ships carrying food could not navigate the ice. Horses were too skinny for travel. Wool was in short supply.

His portrait, which formerly featured on the 100 Krona bill, appeared so sad that he was eventually, after a period of inflation, replaced by a fish.“Even farmers and their children walk around in the frost with much bare skin,” a man named Sigurdur Bjornsson relayed in a letter to the Danish authorities, before proceeding to handily blame the entire situation on the homeless. God, he explained, had no other option than to punish the country for all the drifters going around, lying and stealing, unable to hold a job.

Bombarded with sentimental accounts of Iceland’s annus horriblis, King Ferdrik IV was either touched or frustrated. He had just taken the crown from his father, and his request to Arni entailed a mission never before undertaken: count how many people live in Iceland, and note everything about them: their name, sex, where they live and what they do (particularly if they don’t do anything). Then, the king commanded, write another book assessing the scale of properties in Iceland, with suggestions on how abandoned land could be put back into use. Assess possible “sulphur mining” areas, and the state of harbors and trends in tax collection. Audit administrative and legal practices. And count the cows and all the sheep.

He was to receive a stipend and an assistant for this task, predicted to take two years. It took thirteen.

Understandably, one of the first things Arni did in Iceland while gearing up for the task ahead was to order more coffee from Denmark. It failed to arrive with the bimonthly ship. In a letter found by historians, one lawmaker at Alþingi, apologizing for the lack of good service, offers to send him a quarter-pound, regretting how little he had and noting his distaste for the drink. Coffee and tea was for Danish officials, if anyone. And so, as a native, Arni may have been “Iceland’s first caffeine addict,” suggests history professor Mar Jonsson, author of Arni’s most extensive biography.

He was also the first man in the world to conduct a complete census of an entire country. Nearly exhausting the nation’s paper supply, district commissioners summoned people for headcounts and completed the assignment within seven months, before the annual Alþingi gathering. Every region sent its officials with the results of the census to Þingvellir for official delivery to Arni and his assistant. Parliament’s agenda that session, as noted in Alþingi-books, began with a trial over a woman accused of killing a baby (found guilty and executed by drowning) and three men accused of theft (found guilty and executed by hanging). Third item: after tallying the census results, Alþingi revealed that the people of Iceland totaled 50,358. Minus, er, the four criminals that parliament just executed. And the 497 that were accidentally counted twice, as discovered two centuries later when historians pored over the files, then collecting dust in Copenhagen, having been totally ignored upon their release. Further frustrating this epic exercise in bureaucracy, the population was hit by a great smallpox epidemic three years later and the population plunged to 30,000 people.

“After the outbreak there was at least enough food to go around,” noted one history book, in the kind of outrageous optimism extreme circumstances can foster.

Arni did not catch the disease, a remarkable stroke of luck given that he spent the deadliest years embarking on the epic “land register,” going from one farm to the next. The prominent scholar of Old Norse clearly did not shake hands with many people. His assistant noted how locals were suspicious of “them questions,” assuming that the king was collecting the data for tax purposes. But the register was meant to reform a stagnant economy based on agricultural methods that had not changed much since the invention of agriculture. Arni was detached from his native rural Iceland—“smelling of perfume instead of alcohol”—but his actions suggest he genuinely cared about the goals of the mission. He stayed years beyond what was expected of him and took a rare stance against administrative and legal corruption, making so many powerful enemies that he eventually had no option but to leave.

“Many of the Icelandic handwritten manuscripts were saved because Arni Magnusson…managed to get the manuscripts out in time.”One of Árni’s greatest achievements as a script collector was his dedication to preserving the small stuff; the single pages and obscure findings that didn’t have immediate value compared with complete skin-books. He was like a hoarder, sniffing about and filling his pockets with tired-looking curios. In the 1943 novel Iceland’s Bell, Nobel Prize-winning author Halldór Laxness depicts Arni Magnússon (re-named Arnas Arnæus) as an obsessive character, discovering vellum leaflets under the bed of an old woman:

“The things our dear old ladies hoard,” the character muses over the priceless find.

The land register was completed in 1712 and remains a remarkable documentation of 18th century Iceland. Without the insights provided by the register, books like Iceland’s Bell would not have had the historical material required. But it did not lead to reform as initially intended. It wasn’t even translated into Danish. Arni left the country during a time of war between Denmark and Sweden. Denmark, with England’s support, had attacked Sweden, who were weak from a war with Peter the Great and the Russian Empire. So Arni packed up the manuscripts he had accumulated, along with the detailed land register, into 55 wooden boxes. He decided to wait to ship them until after the Danes had pushed back the Swedish military ships. Eight years later, a convoy of 30 horses traveled from the Skálholt church (near Geysir) to Hafnarfjörður (near Reykjavík) carrying one of the most precious cargoes in the history of a country that so often struggled to make anything other nations would want.

*

And so the precious cargo sat, tucked away in Árni’s house in Copenhagen, until a day in 1728 that would change the face of the city forever.

On a windy Wednesday evening, October 20th, a seven-year-old boy accidentally knocked over a candle. After a warm, dry summer, in the face of strong gusts, the flames quickly caught and spread from house to neighboring house, raging larger and larger. Firefighters had conducted a drill earlier in the day to test hoses; many of them had topped off the exercise with a few pints and now were drunk. They struggled to bring pumps to the fire through winding streets full of panicked civilians. To make it worse, the water supply in that part of the city was cut off due to construction. When orders came down to fetch water from the canals surrounding the city, the city’s panicked military commander ordered the city gate closed, fearing desertion. The fire raged all night, and by Thursday morning, the fire chief was so exhausted and overwhelmed that he…got drunk. In short, bungled responses turned the accident from a small fire into absolute devastation.

Arni, racing against time, was piling his precious books into a horse-drawn carriage with the help of servants and two friends.By morning, Arni was beginning to see that the fire was not under control. He went to work, trying to rescue his precious library. Elsewhere, the unfortunate fire brigade started firing cannons at already-burning houses to make them collapse; when that didn’t work, they started trying to blow them up with gunpowder. This (perhaps predictably) backfired when the gunpowder exploded early, killing people and igniting more nearby buildings, including a church where people had stored their property to keep it safe. By then it was the largest fire in the history of Copenhagen.

Arni, racing against time, was piling his precious books into a horse-drawn carriage with the help of servants and two friends. The fire was spreading to City Hall, destroying the city archives; at the same time, new fires were breaking out, started by embers carried by the wind. One after another, the buildings of the University of Copenhagen went up in flames: the community building, the head building, the anatomy theatre. At last, the fire reached the university library, housed in the attic of a church. The entirety of the library—35,000 volumes—lay there. They included archival documents from Niels Krag and Tycho Brahe, some of the first printed versions of Aristotle’s works, scientific works dating to the 15th century; precious volumes about medieval history with only a single existing copy. The ceiling gave way. Every single volume tumbled into the flames, gone forever—save a few (illegally lent) works that happened to be checked out. Next were the houses of the university professors: all their notes, their manuscripts, the personal collections, gone.

One can only imagine what Arni was feeling. Imagine the air acrid with smoke; the screams of people fleeing, trying to save their houses; the crash of buildings collapsing in the distance. Surrounded by precious, ancient volumes which he knew could never, ever be replaced, he hurriedly filled the horse carts. In the distance, the Round Tower was engulfed in flames, destroying Tycho Brahe’s celestial globe, made in 1570 and the first in history. Church bells sang out Thomas Kingo’s Turn your anger, Lord, by mercy, before that church too caught fire, sending the bells clanging into the fire below. The fire brigade tried setting off charges again, this time accidentally burning down the vice mayor’s house.

Arni managed to rescue three or four loads of his books, struggling through the crowd to a friend’s house. At last, the fire spread too close for him to rescue any more. His own home burned down at around 4 that afternoon.

The fire raged until October 23rd. In the end, nearly half the medieval section was destroyed, totaling about a third of the city. A full fifth of the residents of Copenhagen had been left homeless. This was awful, but the cultural destruction was truly staggering: virtually all of the books of Copenhagen had been destroyed. The University of Copenhagen had lost everything; at Borchs Kollegium, 3,150 volumes burned; the city archives were lost. Arni had managed to save an impressive amount of his own collection, considering. He rescued most of his books of sagas, including most of the oldest and most valuable core of the collection, the ancient vellum books. But he lost his own work, his notes and writing, and most of the printed books, including the last known copy of the Breviaria of 1534, the first book printed in Iceland.

“Almost all the books in Copenhagen were incinerated. But many of the Icelandic handwritten manuscripts were saved because Arni Magnusson…managed to get the manuscripts out in time,” attests Professor Morten Fink-Jensen, a researcher and University of Copenhagen historian. This did little to console the now-homeless Arni. In the harsh winter that followed the fire, Arni had to move three times, all the while wrestling with his own losses, the extent of which he couldn’t even measure since he’d never taken a full inventory. By the following Christmas Eve, he fell ill. Upon his death, he bequeathed his remaining collection—nearly 1,600 Icelandic manuscripts—to the university. Today, the most important ones are collected in the Arnemagnean Institute, located both in Copenhagen and Reykjavík. There, Icelanders are once again, employed reading, writing, and interpreting old scripts. Like Tolkien babysitters, watching over the country’s most precious cultural contribution.

__________________________________

From How Iceland Changed the World by Egill Bjarnason, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 Egill Bjarnason.