If you had to group pitches into two categories, you would choose “fastball” and “other.” The “other” makes pitching interesting. If the ball went straight every time, pitchers would essentially be functionaries, existing merely to serve the hitters. Long ago, that is just what they were, as the name implies. Think of pitching horseshoes: you’re making an underhand toss to a specific area. That was pitching for much of the 1800s. For 20 years—1867 through 1886—batters could specify whether they wanted the pitch high or low. The poor pitcher was forced to comply.

Baseball might have continued as a test of hitting, running, and fielding skills had pitchers not discovered their potential for overwhelming influence. What if they could make the pitch behave differently? Long before cameras and websites could classify every pitch into a type, many of the offerings intended to deceive a hitter—in-shoots and out-shoots, in- curves and out-curves and drops, in the old parlance—were largely known as curveballs. The “other” was, simply, everything that wasn’t a fastball.

In researching the history of curveballs at the Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, I was struck by how many people claimed to be the inventor. In 1937 The New York Times published an obituary of a man named Billy Dee of Chester, New Jersey, who was said to have invented the curveball in 1881. Dee threw a baseball with frayed seams and, intrigued by its movement, said he practiced and practiced until “I soon was able to loop the old apple without the benefit of the damaged seam.” Sounds impressive—but what’s this? A 1948 Times obituary of one George McConnell of Los Angeles, “an old- time Indian fighter” who “decided that the ‘English’ being put on billiard balls could be used with a baseball.” That was in 1878.

There are many more such stories in the files and the history books at Cooperstown. Fred Goldsmith has a case, like James Creighton and Phonie Martin and Alvah Hovey and more. There’s even a hoary old Ivy League debate from the 1870s: Did Charles Avery of Yale curve first, or Joseph Mann of Princeton?

[Cumming’s] story links the discovery of the curveball to the curiosity of a 14-year-old boy on a beach in Brooklyn. What could be more American than that?Peter Morris untangles it all in A Game of Inches, quoting a letter from Mann to the Times in 1900 that sums it up neatly: “As long as baseball has been played and baseballs have had seams with which to catch the air, curve balls have been thrown.”

Mann goes on to assert that, in spite of this, no one thought to use those curving balls for pitching until he did so in 1874. Then again, Mann admits he was inspired by watching Candy Cummings one day at Princeton. Mann said Cummings’s catcher told him he could make the ball curve, though it did not do so that day.

Confused yet? The plaque in the Hall of Fame gallery for W. A. “Candy” Cummings boldly settles things in seven gilded words: “Pitched first curve ball in baseball history.” The plaque dates this discovery to 1867, when Cummings was the amateur ace of the Brooklyn Stars. History should always be so easy.

The Cummings backstory is so indelible, so rich in imagery, that if it’s not true… well, it should be. It has never been debunked and would be impossible to do so. Cummings is practically a charter member of the Hall, going in with the fourth class of inductees in 1939. His story links the discovery of the curveball to the curiosity of a 14-year-old boy on a beach in Brooklyn. What could be more American than that?

Here is how Cummings described it for Baseball Magazine in 1908:

In the summer of 1863 a number of boys and myself were amusing ourselves by throwing clam shells (the hard shell variety) and watching them sail along through the air, turning now to the right, and now to the left. We became interested in the mechanics of it and experimented for an hour or more. All of a sudden it came to me that it would be a good joke on the boys if I could make a baseball curve the same way.

Cummings was born in 1848 in Ware, Massachusetts, and various accounts say that he played the old Massachusetts game before moving to Brooklyn. Cummings himself did not mention this in his retelling of the curveball’s origin story, but to Morris, it was a significant detail. In the 1850s, pitchers in Massachusetts were permitted to throw overhand, which made curveballs easier to throw.“

He had probably seen rudimentary curves thrown as a youngster in Massachusetts, and when he moved to Brooklyn and began playing the ‘New York game,’ the delivery restrictions made the pitch seem impossible,” Morris wrote. “Yet the example of throwing clamshells made him think that it might be possible, and his arm strength and relentless practice enabled him to realize his ambition.”

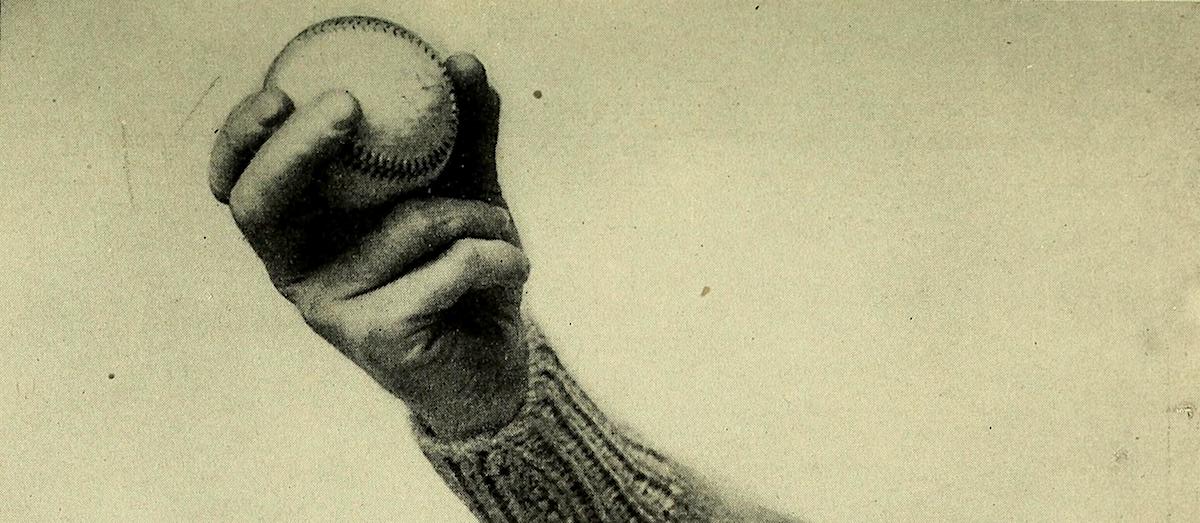

Cummings emphasized two points: his solitary persistence in perfecting the pitch despite ridicule from his friends, and the physical toll imposed by the delivery restrictions of the day. Pitchers then worked in a four-by-six-foot box, and could not lift either foot off the ground until the ball was released.“

The arm also had to be kept near the side and the delivery was made with a perpendicular swing,” Cummings said, in an undated interview published after his career. “By following these instructions it was a hard strain, as the wrist and the second finger had to do all the work. I snapped the ball away from me like a whip and this caused my wrist bone to get out of place quite often. I was compelled to wear a supporter on my wrist all one season on account of this strain.”

Cummings left Brooklyn for a boarding school in Fulton, New York, in 1864. He tinkered with his curveball there—“My boy friends began to laugh at me, and to throw jokes at my theory of making a ball go sideways”—and joined the Star Juniors, an amateur team in Brooklyn. From there he was recruited to the Excelsior Club as a junior member, in both age and size: he would grow to be 5 foot 9, but his weight topped out at 120 pounds.

In the curveball, though, Cummings found an equalizer. He showed that pitchers of all sizes could rely on movement and deception—not simply on power—to succeed. Soon, the notion would be ingrained as baseball fact that a pitcher with dominant stuff could humble even the brawniest hitter. Cummings began to prove this in 1867, with the Excelsiors in a game at Harvard.“

A surge of joy flooded over me that I shall never forget,” he wrote in the Baseball Magazine piece. “I felt like shouting out that I had made a ball curve; I wanted to tell everybody; it was too good to keep to myself. But I said not a word, and saw many a batter at that game throw down his stick in disgust. Every time I was successful I could scarcely keep from dancing from pure joy. The secret was mine.”

The movement could be very erratic, Cummings conceded, but in time he learned to control it, and to manipulate the umpires. When the ball started at a hitter’s body, and caused him to jump before bending into the strike zone, the umpire called it a ball. Cummings adjusted by starting the pitch in the middle so he could get strikes, even though the movement carried it away.“

When it got to the batter it was too far out,” he said. “Then there would be a clash between the umpire and the batter.”

By age 23 Cummings was a pitcher for the New York Mutuals of the National Association. The pitching was done from 45 feet away, in that box, with a sidearm motion—and the numbers were similarly unrecognizable today. Cummings started 55 of the Mutuals’ 56 games, working 497 innings and giving up 604 hits, with a 33-20 record and a 3.01 earned run average. When the National League began in 1876, Cummings pitched for the Hartford Dark Blues and went 16-8. He went 5-14 for the Cincinnati Reds in 1877, his final season.

A curious contemporary, Bobby Mathews, would go on to have more success. Mathews was even shorter than Cummings—just 5 foot 5—and as their careers overlapped in the National Association, Mathews was one of the few who could mimic Cummings’s sidearm curve. Generations of pitchers would follow Mathews’s example: see something interesting, study it, and make it their own.“

He watched Cummings’ hands carefully, noting how he held the ball and how he let it go, and after a few weeks’ careful practice in the same way could see the curve in his own delivery,” explained an 1883 article from The Philadelphia Press, unearthed by Morris. “Then he began to use it in matches, striking men out in a way that no one but Cummings had ever done before, and in a short time he was known as one of the most effective pitchers in the field.”

That was the first of three consecutive 30-win seasons by Mathews for the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association. He did not make the Hall of Fame, but he followed Cummings as the curveball’s most prominent practitioner, carrying the pitch through the sidearm era and helping to establish it as fundamental to the game.

Assuming that you believed in it at all.

*

For decades after Cummings’s last pitch, many people doubted the very notion that a ball could curve. It was a staple of baseball debate that the curveball just might be an optical illusion. A favorite exercise for skeptics was to challenge a pitcher to prove his powers by bending a ball around a series of poles. This happened a lot.

“The majority of college professors really believe that the curve ball was as impossible as the transmutation of gold from potato skins,” said a man named Ben Dodson, in the Syracuse Herald in 1910.

Dodson said he witnessed a demonstration at Harvard by Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, probably in the 1880s. Radbourn—whose “pitching deity; dapper gent” persona would one day make him a Twitter sensation—was an early hero of the National League. In 1884, for the Providence Grays, he was 59–12 with a 1.38 ERA and 73 complete games. The professors, safe to say, had a lot of misplaced confidence when they arranged their poles and dared Radbourn to throw curves to his catcher, Barney Gilligan.

“Radbourn, standing to the right of the pole arcade, started what appeared to be a perfectly straight delivery,” Dodson said. “It turned with a beautiful inward bend and passed behind the pole just in front of Gilligan—an inshoot, and a corker. He repeated this several times. Then, standing inside the upper part of the pole- zone, he threw out-shoots that went forty feet dead on a line, and swung out of the arcade.”

It was a staple of baseball debate that the curveball just might be an optical illusion.Dodson went on to describe Radbourn’s “drop balls,” though not all of these pitches were curves, as we think of them today. Radbourn threw a wide array of pitches that would now be classified as curveballs, changeups, sinkers, screwballs, and so on. That day at Harvard, his charge was to prove that something besides a fastball really did exist, and Dodson, for one, considered the matter closed.“

It was a wonderful demonstration and settled the argument about curve pitching forever,” he said. “And yet—because they never thought about publicity in those days—not a reporter was at hand, and the story lives only in the memories of those who saw it done.”

What a pity. For some, the matter was still debatable midway into the next century, as Carl Erskine recalls. As a minor leaguer, Erskine had gotten a tip from a rival manager, Jack Onslow, who told him he was telegraphing his curveball by the way he tucked it into his hand. In Cuba before the 1948 season, Erskine taught himself a new grip and trusted it one day to preserve a shutout after a leadoff triple in the ninth. The circumstances mattered, because the team had a standing bonus of $25 for a shutout.

“My inclination was, ‘Oh boy, I gotta go back to my old curve, I gotta get this shutout,’ ” Erskine says. “So I had a little meeting on the mound with myself, tossed the rosin bag: ‘You made a commitment that you weren’t gonna go back to the old curve; stick to it’—and I got the side out without that run scoring. From then on, I had good confidence in that, and the rest is history.

”Erskine’s history included five pennants with the Dodgers and one narrowly missed brush with infamy. On October 3, 1951, he was warming up in the bottom of the ninth inning at the Polo Grounds alongside Ralph Branca, with the pennant at stake against the Giants. Manager Charlie Dressen called to the bullpen and asked a coach, Clyde Sukeforth, which pitcher looked better.

Dressen liked the curveball; he would say of the slider, disdainfully: “They slide in and slide out of the ballpark.” But when Sukeforth reported that Erskine was bouncing his curve, Dressen chose Branca.

“People say, ‘Carl, what was your best pitch in your 12 major league seasons?’ ” Erskine says with a laugh. “I say it was a curveball I bounced in the bullpen at the Polo Grounds. It could have been me.”

Instead it was Branca who threw the fateful fastball that Bobby Thomson lashed into the left field seats—the celebrated “Shot Heard ’Round the World” that gave the Giants the pennant. We’ll never know how Thomson might have handled Erskine’s curve, but the Giants were stealing signs, so he might have hit that, too.

In any case, it was around this time that Erskine’s pitch all but buried the tired debate about its veracity.

“TV came in around the late ’40s and there was a show early on, Burgess Meredith was the emcee, called Omnibus,” Erskine explains. “They sent a crew to Ebbets Field one day and they asked for me and Preacher Roe, who was a left-hander who threw an overhand curve, to come out early. The purpose was to film us throwing a curveball, and to prove or disprove whether a ball actually curved.

“So we got ready to go out there, and I took a new baseball and scuffed it up a little bit in order to make sure I had good bite on it. So I warmed up and the director of this film stood behind me and said, ‘I’m not a baseball guy, so I don’t know what I’m looking for here. Could you throw me a couple of curveballs so I could see what it is I’m trying to film?’ So with this scuffed-up baseball I threw an overhand curveball and it broke big. And this director says, ‘My God, is there any doubt?’ So he was a novice at seeing pitches, but the first one he saw: ‘Holy cow! There’s no question!’“

So they put that show on, Preacher threw from the left side and I threw of course from the right side, and then they used this dotted line that was superimposed somehow on the film. And you could basically say, well, there is no doubt: yes, a rotating pitch can break out of a straight line and be a curveball.”

As Erskine described the mechanics of the curveball, he spoke of using the middle finger to apply pressure to the ball, lead the wrist, and help generate tight rotation. The index finger is almost in the way, he said, which reminded him of a character he met in the “3- I” League (Iowa, Indiana, Illinois), where he played in 1946 and ’47.

“One of the greatest all- time pitchers that I met when I was in the minor leagues was Mordecai Brown,” Erskine says. “He lived in the Terre Haute House—that was the Phillies’ affiliate—and he would come down and talk to us in the lobby, show us his hand, where he had this farm accident and it took away not only his first finger of his right hand, it even took the knuckle. So he had a hand that had three fingers—naturally, his nickname was ‘Three Finger’ Brown—and it gave him the ultimate best use of that second finger for the curveball, because the first finger was out of the way completely.

“He was a real gentleman, always dressed in a shirt and tie. Naturally, an old gentleman by that time, and we were just kids in the minors. But we were fascinated to talk to him, and he was anxious to show us his hand, tell us how he learned to pitch without the first finger, or even the first knuckle. It gave him the ultimate advantage if you want to throw that curveball with lots of tight rotation. The second finger became his first finger. So he must have had a wicked curveball.”

Indeed he did, and his story captivated fans. Mordecai was five years old, helping his brother cut food for horses at their uncle’s farm in Nyesville, Indiana, when his right hand slipped into the feed chopper. The accident mangled every finger, and a doctor amputated the index finger below the second joint. A few weeks later, his hand still in a splint, Mordecai and his sister were playing with a pet rabbit, trying to make it swim in a tub. Mordecai lost his balance and smashed his hand on the bottom of the tub, breaking six bones.

It was a brutally painful, almost slapstick way to form the perfectly gnarled curveball hand. Nobody could mimic Brown’s curveball.

“When Brown holds the ball in that chicken’s foot of a hand and throws it out over that stump, the sphere is given a peculiar twist,” wrote the Chicago Inter Ocean in 1910, at the height of Brown’s fame with the Cubs. “It behaves something like a spitter. It goes singing up to the plate, straight as a drawn string, then just as the batter strikes at it, it darts down like a snake to its hole.”

On his way to the Hall of Fame, Brown went 49-15 with a 1.44 ERA across the 1907 and 1908 seasons. He won all three of his World Series games in those years, allowing no earned runs over 20 innings to lead the Cubs to consecutive championships. He died in 1948, shortly after he would have met the young Carl Erskine.

![]()

From K: A HISTORY OF BASEBALL IN TEN PITCHES by Tyler Kepner. Used with permission of the publisher, DOUBLEDAY. Copyright © 2019 by Tyler Kepner.