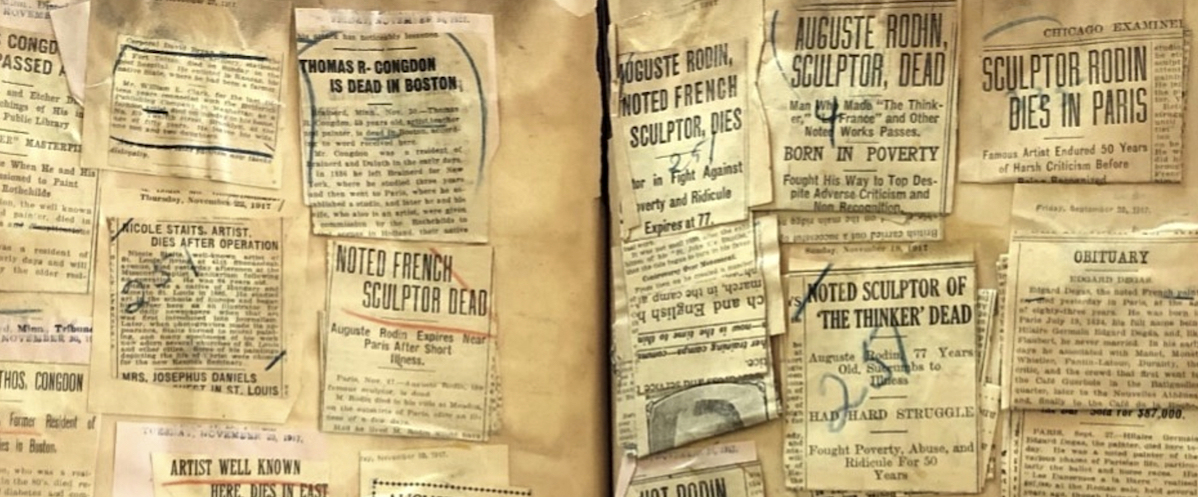

When I open the scrapbooks, tiny flakes of brittle, brown paper fall away from their edges, warning me that my compulsion to read could hasten the demise of these strange old volumes. Stored in my workplace in the archives of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, they are filled with thousands of newspaper clippings that report the deaths of painters, sculptors, and photographers of the early 20th century. I first surveyed them four years ago, while hunting through old books and files for historical images to illustrate Making the Met, an exhibition and catalogue that celebrated the museum’s 150th anniversary in 2020.

The Archives is a treasure trove of unique documents and artifacts of the Met’s founding and early years, and I am fortunate to have spent much of my career preserving and sharing the history of one of the world’s foremost cultural institutions. But I quickly discerned that artist obituaries were irrelevant for Making the Met and was about to reshelve the scrapbooks, when my attention fixed on a headline glued to the page to which I’d randomly turned: FAMOUS ARTIST DIES PENNILESS AND ALL ALONE. Curious, I carefully leafed through the tome and found myself spellbound by a panoply of heartbreaking tales.

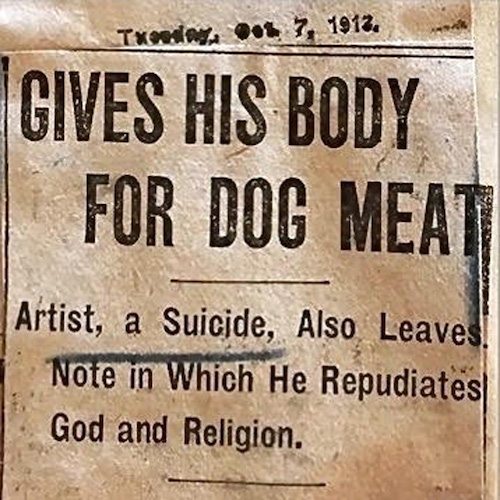

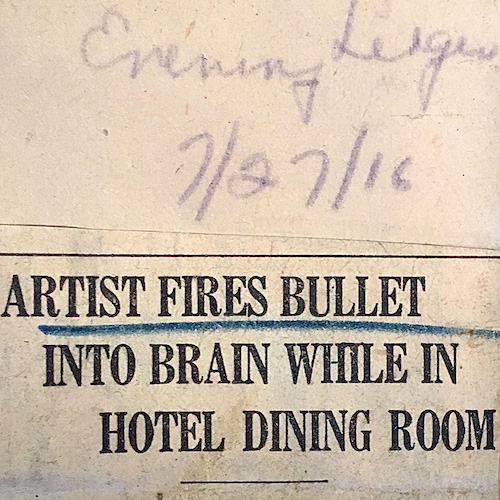

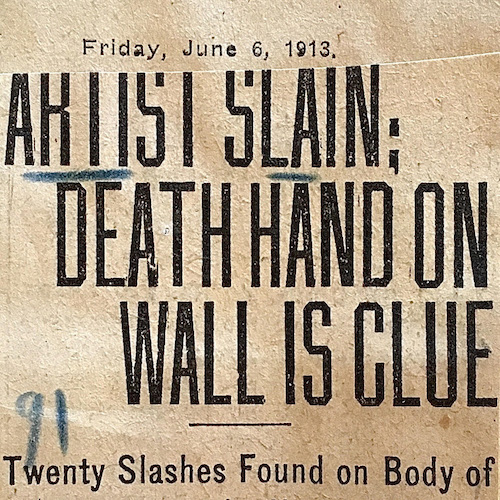

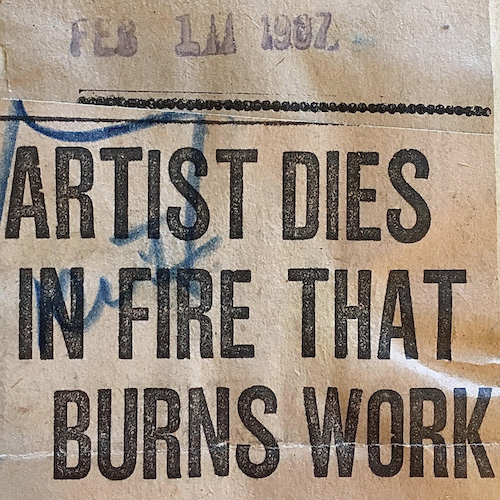

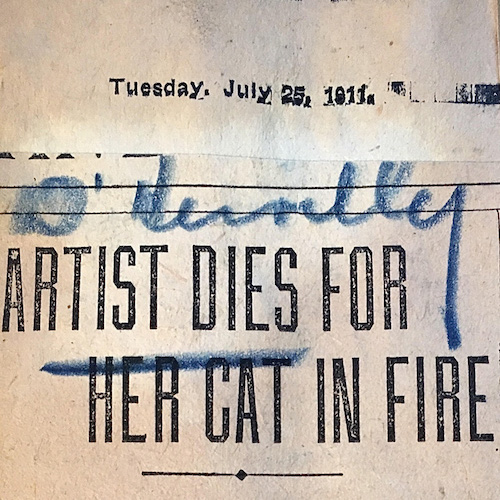

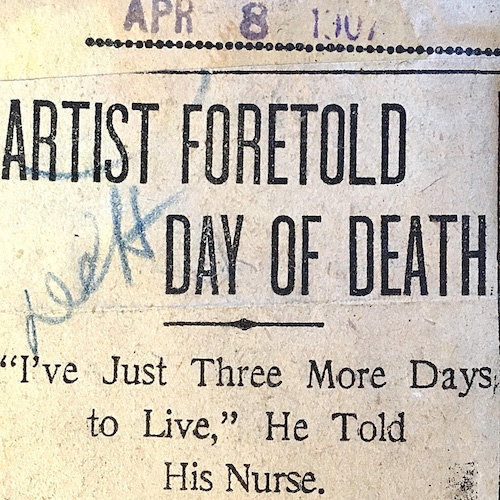

Artist obituary scrapbook, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. All photographs by the author unless otherwise noted.

Artist obituary scrapbook, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. All photographs by the author unless otherwise noted.

Some are formal obituaries of art world luminaries whose names remain familiar today, such as Auguste Rodin. Others describe the passing away of artists revered in their own time, but whose work has since fallen from fashion and is today little known. Hundreds more of the clippings, though, recount more gruesome stories: the demise of artists obscure at the time and now utterly forgotten, many of them suicides, or victims of bizarre accidents, murders, or disease. These grim fragments retrieved from the past reveal disturbing themes and motifs once prevalent in mass media portrayals of creative people.

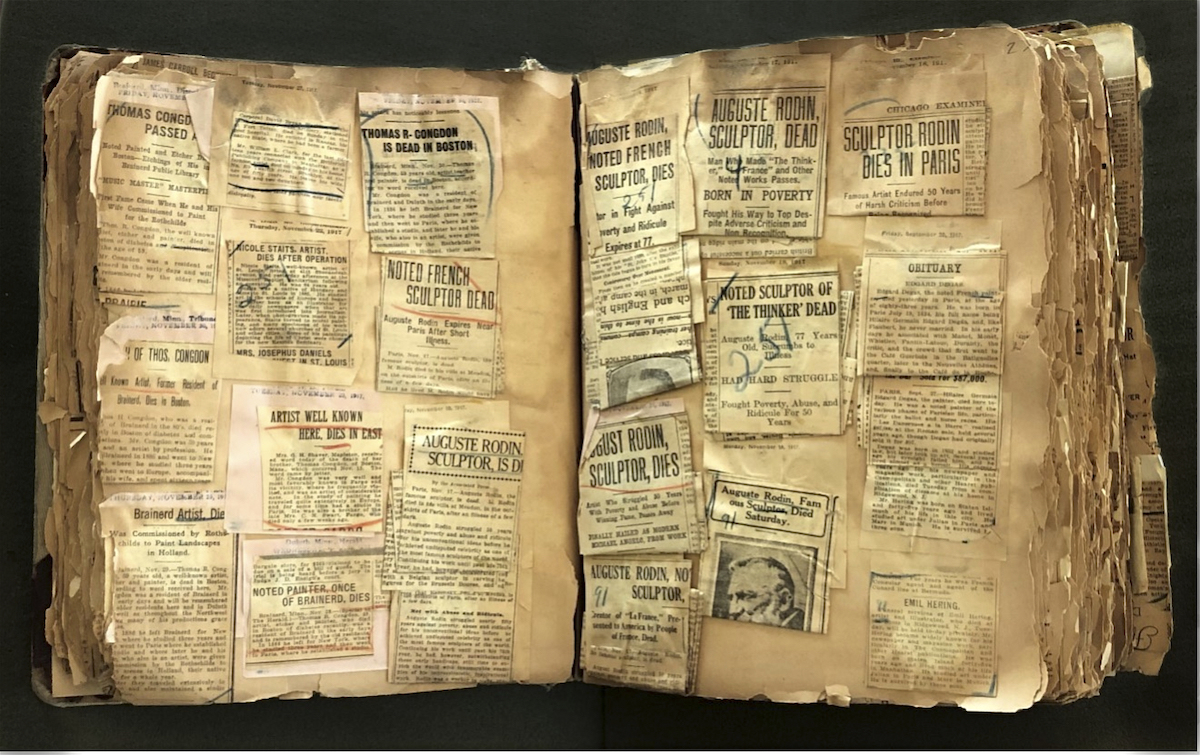

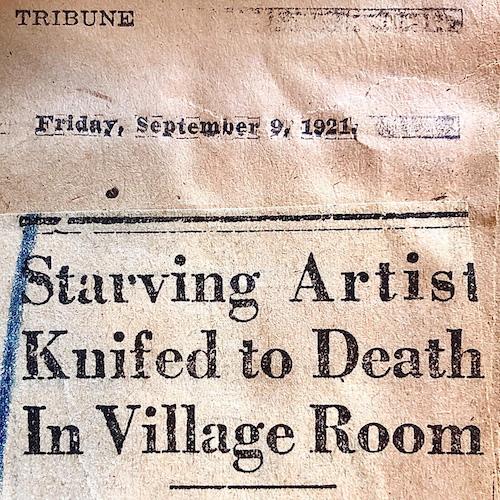

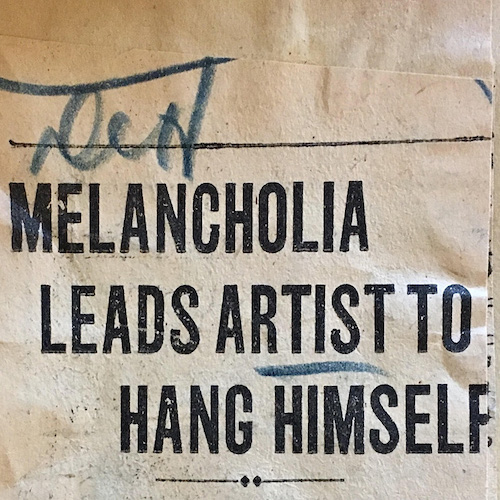

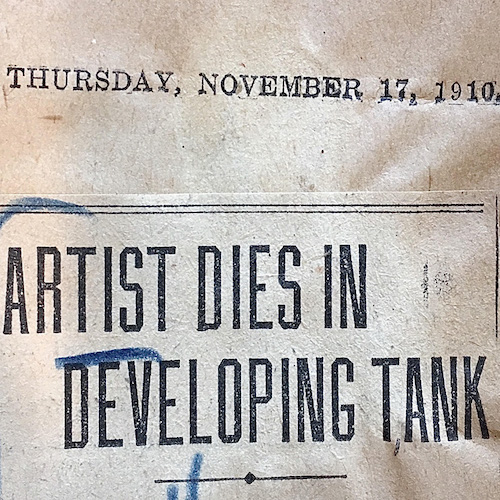

The most jarring stories are titled and told in a sensationalized style that emphasizes personal idiosyncrasies of the victims and the graphic details of their deaths. Typical of the era’s crass tabloid journalism, they were crafted to wring maximum drama out of misfortune, and to excite and fix the attention of readers susceptible to raw emotional appeal and voyeurism. Their authors drew upon and reinforced stereotypes of artists as indigent, debauched, obsessed with greatness, eccentric, or suffering from mental illness.

Many news reports observed that artists routinely suffered poverty, and even those of great renown were liable to die of hunger or in squalor while fanatically pursuing their vocation. Dire material circumstances and failure to sell work or secure patronage drove some to depression and suicide, and reporters graphically described methods by which artists ended their own lives.

Numerous stories recounted deaths in the studio, while toiling at the easel, or amidst remnants of an oeuvre. A few artists were said to have passed while putting the finishing touches to masterworks that might have won them recognition at last. Another theme presented artists as murder victims, often stemming from love quarrels or unorthodox romantic entanglements associated with a bohemian lifestyle.

Many stories reflected on the whims of fate by describing, in harsh detail, bizarre accidents like conflagrations that consumed artists alongside their creations. Others describe creative lives ended in momentous global tragedies, including sinking of the Titanic, the First World War, and the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic.

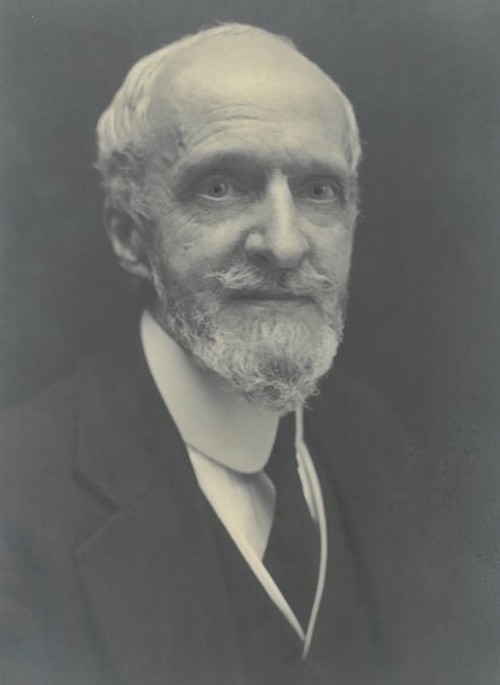

Who compiled this macabre archive, and why? I noticed that many clippings are marked in blue crayon with the name “D’Hervilly” or an abbreviated “D’H”. I searched through century-old museum employee rolls in the archives, and found a match for the unusual surname: Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly, hired in 1894 as an office clerk. Details of his early life are scant, but online research turned up a reference to a painting by D’Hervilly titled “Chasseur” in the digitized catalogue of an 1887 exhibition at the National Academy of Design. No more evidence of his artistic production has yet surfaced, though this tantalizing clue helps explain his professional orientation to the museum.

At age 44, D’Hervilly sent to the Met’s director a beautifully handwritten application letter, followed up with an epistolary poem illustrated with a watercolor image of a medallion. The overwrought style attested to D’Hervilly’s creative ambition, though he confessed willingness to accept any position offered as he was “unable to follow my profession, the Fine-Arts, owing to inadequate means.” His odd pitch was perfectly aimed at the Met’s colorful chief executive Luigi Palm di Cesnola, an Italian-American veteran of the US Civil War who micromanaged staff, craved their respect, and prized loyalty. Cesnola assigned D’Hervilly to calligraphy invitations for Met special events, sort business correspondence, and tend to other administrative matters.

Clipping marked with the name “D’Hervilly”

Clipping marked with the name “D’Hervilly”

After laboring for a decade at clerical tasks, D’Hervilly was in 1906 promoted to Assistant Curator of Paintings. In this new role he compiled a checklist of American paintings at the Met, and updated its catalogue of European pictures, leaving behind in the Archives his extensive and detailed research notes. D’Hervilly guided access to galleries by tour groups, and recorded statistics about school classes, trade organizations, and others who visited the museum for learning and inspiration. He took special interest in art students who honed their talent copying old master paintings and closely monitored a locker room where they stored supplies and hung their overcoats.

He coordinated press previews for special exhibitions and hosted reporters for private showings of new acquisitions. Believing that newspapers served the museum as both a publicity tool and resource for self-documentation, D’Hervilly oversaw the assembly of scrapbooks that preserved thousands of newspaper stories about a wide array of Met happenings. The construction of new museum wings, milestone art purchases, deaths and legacies of benefactors, and the launch of educational programs were extensively documented in this press archive.

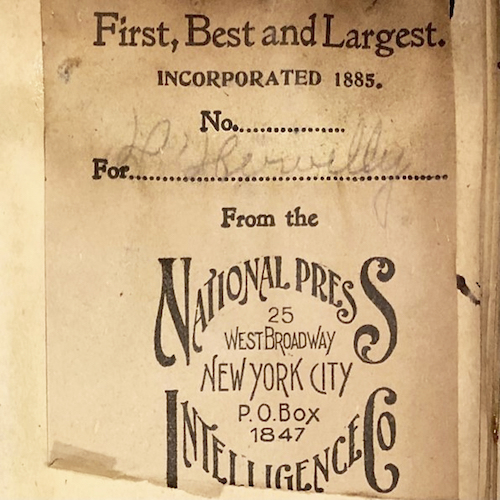

National Press Intelligence Co. label marked with the name “D’Hervilly”

National Press Intelligence Co. label marked with the name “D’Hervilly”

D’Hervilly’s preferred news source was the National Press Intelligence Co., one of many “clippings bureaus” that thrived a century ago. Richard K. Popp, a journalism professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, has researched these businesses extensively, finding that the earliest were established in Europe around 1880 to cater to actors, artists, and authors eager to collect reviews of their productions and document celebrity. Soon, the value of absorbing deep wells of press intelligence from around the globe was clear to business leaders, politicians, and cultural institutions like the Met.

The first American clippings bureaus were established in the mid-1880s, and dozens operated nationwide by the turn of the century. Clippings bureau employees—mostly women—read hundreds of daily papers each day, bearing in mind a plethora of personal names, terms, and concepts requested by customers. When readers encountered a target phrase they underlined it with a bold stroke of blue pencil and often scrawled the name of a client, like the distinctive “D’H” in the Met scrapbooks. Marked-up sheets were clipped apart, then isolated stories were glued to header slips with a citation of the name and date of the publication in which they were found. These were bundled and delivered to subscribers at a price of $.04 cents each.

Words and phrases in Met batches included mentions of the institution by name and references to its trustees and staff, search parameters which harvested thousands of clippings, which were then, in turn, pasted by museum clerks into scrapbooks from the late 19th century until the 1960s.

In 1906, the same year he was promoted to Assistant Curator of Paintings, D’Hervilly apparently ordered National Press Intelligence to collect and send him stories about deaths of artists, the only theme in the press archive not Met-specific. Over the next few decades, these obits accumulated to fill nearly 500 densely-packed pages bound into the two overstuffed volumes that I stumbled on in the Archives 112 years later. Jules Breton, a renowned painter of French rural scenes, is the first artist memorialized on their opening pages, in lengthy dispatches flagged with a blue “D’H” and dated July 6-8, 1906.

It is poignant to discover that only a few newspapers printed brief accounts of D’Hervilly’s own passing on April 7, 1919, though his colleagues were sure to paste these clippings in the scrapbook. He died of heart failure at home in Harlem while preparing for his commute to work; a headline declared him A SLAVE OF DUTY AT ART MUSEUM who never took vacation and always ate lunch at his desk.

Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly’s massive, collage-like chronicle of the deaths of artists of his time seems a crowning professional achievement,, and the timing of his decision to launch the effort feels charged with meaning.*

As an archivist at the Met, I safeguard the scrapbooks that D’Hervilly made so that people of the future may consider their mysteries. As a personal project, I photograph some of the most astonishing headlines, research artists they describe, and present my findings in publications like this one. This exhumation can feel eerie and invasive, like the opening by archaeologists of an ancient tomb. I sometimes question my impulse to expose old obituaries to the light of the present day, and I crop many images to omit the names of the deceased, conferring on them an anonymity that I hope protects the dignity of their final repose. During especially bleak phases of the pandemic, absorbing too many reports of artist deaths by Covid, I have set this work aside entirely. But the impulse to explore this mournful theme revived again and again, and I have come to recognize that the scrapbooks are compelling not only because they document artist deaths, but because they stimulate ideas about artist lives. I choose to share these stories to inspire wonder at the unique challenges artists face, the exceptional risks they take, and the strange turns of fate that often thwart their efforts.

Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly, undated photograph, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly, undated photograph, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Viewed in retrospect, Arturo B. de St. M. D’Hervilly’s massive, collage-like chronicle of the deaths of artists of his time seems a crowning professional achievement,, and the timing of his decision to launch the effort feels charged with meaning. Newly promoted to curate masterpiece paintings, had he given up for good his own artistic ambition? Was the composition of these morbid tomes a veiled acknowledgement of the passing away of his creative aspiration? Did he identify with the hundreds of uncelebrated artists whose fates the news clippings recorded in grim detail? Perhaps, instead, his intent was more mundane, and compiling them was an expedient for collecting useful biographical data as he catalogued pictures in the Met collection that were made by recently deceased artists.

Whatever their purpose to D’Hervilly and his colleagues, viewers today can study, interpret, and respond emotionally to these scrapbooks on multiple levels. They offer clear, factual accounts of how the lives of a few hundred artists ended. They exhibit some of the crass, sensationalist techniques deployed by the press in the heyday of yellow journalism to influence how millions of readers thought about artistic types. But in addition to their evidentiary value for historical knowledge, they have an intrinsic, aesthetic worth. Composed of dense, decaying layers of folded browned paper, dried glue, faded black ink, and bold strokes of blue crayon, they are fragile memento mori, deeply redolent of time’s passage. Their literary style is by turns brutal, satiric, and laudatory, but never dull. Curators like D’Hervilly and archivists like me are devoted to the solemn work of gathering, protecting, and sometimes even creating such powerful artifacts so that our contemporaries and future generations can feel their impact with all the force of great art.