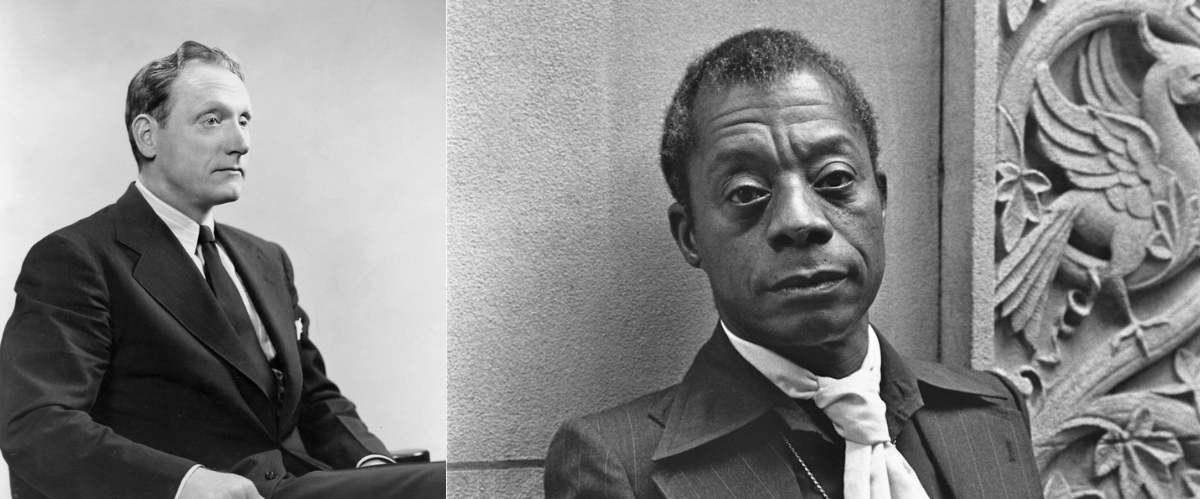

This interview was conducted on April 27, 1964. It first appeared in Robert Penn Warren’s 1965 book, Who Speaks for the Negro?

*

Robert Penn Warren: In what sense, Mr. James Baldwin, do you think the Negro revolution is a revolution?

James Baldwin: Well that’s a tough one to answer because I’m not always sure that the word “revolution” is the right word. I myself use it because I don’t know of any other. It’s not as simple as a revolution of one class against another, for example. It is not as clear-cut as the Algerian revolution against the French. It is a very peculiar revolution because, in order to succeed at all, it has to have as its aim the reestablishment of the Union. And a great, radical shift in American mores, in the American way of life. Not only does it apply to the Negro, obviously, but it applies to every citizen in the country. This is a very tall order and desperately dangerous, but inevitable in my view because of the nature of the American Negro’s relationship to the rest of the country, of all these generations, and the attitudes the country’s had toward him, which always was, but now has become overtly and concretely, intolerable.

RPW: You say different from a revolution like the Algerian, which means a liquidation of a regime.

JB: That’s right. But it doesn’t apply here at all. Because this is for Negroes to liberate themselves and their children from the economic and social sanctions imposed on them because they were slaves here. Now if Washington DC, had the energy to break the power of people like Senator James Eastland and Senator Richard Russell, so the Negroes began to vote in the South, we would make a large step forward. It seems to me that the South is ruled still by an oligarchy, which rules for its own benefit, and not only oppresses Negroes and murders them but imprisons and victimizes the bulk of the white population.

RPW: You said once in print that the Southern mob does not represent the will of the Southern majority.

JB: I still feel that. It’s mobs that fill the street. Unless one’s prepared to say that the South is populated entirely by monsters, which I’m not. Those mobs that fill the street are a reflection of the terror that everybody feels, at least on the lowest level. And those mobs that fill the street have been used by the American economy for generations to keep the Negro in its place. In fact, they have done the Americans’—North and South, by the way—dirty work for him. And they’ve always been encouraged to do it. No one has ever even given him any hint that it was wrong. And of course they are now completely bewildered. And can only react in one way, which is through violence. The same way that an Alabama sheriff, facing a Negro student, knows he’s in danger. Doesn’t know what the danger is and all he can do is beat him over the head or cattleprod him. He doesn’t know what else to do.

RPW: All revolutions of the ordinary, historical type have depended on the driving force of hope and the driving force of hate. Now, when this is directed against a regime to be liquidated, it’s one thing; when it’s inside of a system, which must be reordered but not destroyed, then the hope/hate ratio might change. I think how the hate is accommodated in this revolution.

JB: The American Negro has had to accommodate a vast amount of hatred since he’s been here. And that was a terrible school to go through. I myself am accused of hating all white people and saying that all Negroes do. I, myself, don’t feel that so much as I feel a bitterness. You can despise white people. You may even have given moments when you want to kill them. But here it’s your brothers and your sisters, whether or not they know that they are your brothers and your sisters. And that complicates it. It complicates it so much that I can’t quite see my way through this.

As for the hope, that is fuzzy too. Hope for what? You know, the best people involved in this revolution certainly don’t hope to become what the bulk of Americans have become. So the hope, then, has to be to create a new nation under intolerable circumstances and in very little time and against the resistance of most of the country.

All the American institutions and all the American values, public and private, will have to change.RPW: You mean the hope is not to simply move into white middle-class values? Is that it?

JB: Well even if that were the hope—it isn’t as a matter of fact— it would not be possible. In order to accommodate me, in order to overcome so many centuries of cruelty and bad faith and genocide and fear, all the American institutions and all the American values, public and private, will have to change. The Democratic Party will have to become a different party, for example.

RPW: How do you envisage the result of this movement, if successful? What kind of a world do you envisage?

JB: I envisage a world which is almost impossible to imagine in this country. A world in which race would count for nothing. In which Americans grow up enough to recognize that I don’t threaten them. Part of the problem here has nothing to do with race at all. It has to do with ignorance and it has to do with the culture of youth.

Warren asks Baldwin about the origins of growing racial pride among some African Americans.

JB: For the first time in American history, the American black man has not been at the mercy of the American white man’s image of him. This is because of Africa. For the first time, the West was forced to deal with Africans on a level of power. And that image of the shiftless darkie was shattered. Kids, people had another image to turn to, which released them. It’s very romantic for an American Negro to think of himself as an African. But it’s necessary in the re-creation of his morale.

RPW: In the matter discussed a while ago by W.E.B. Du Bois, and many other people since, of the split in the psyche of the American Negro—you have written something about it along this line—the tendency to identify with the African culture or African mystique, or the mystique noir, or even the American Negro culture as opposed to American white culture. The tendency to pull in that direction as opposed to the tendency to accept the Western, European-American white tradition, as another pull. Do you feel this is real for yourself?

JB: How do I answer that? It was very hard for me to accept Western European values because they didn’t accept me. Any Negro born in this country spends a great deal of time trying to be accepted, trying to find a way to operate within the culture and not to be made to suffer so much by it, but nothing you do works. No matter how many showers you take, no matter what you do. These Western values absolutely resist and reject you. So that, inevitably, you turn away from them or you reexamine them. Because it is something that slaves knew and the masters haven’t found it out yet; the slaves who adopted that bloody cross knew the masters could not be Christians because Christians couldn’t have treated them that way. This rejection has been at the very heart of the American Negro psyche from the beginning.

Warren asks Baldwin about the attraction to Africa that an increasing number of black people had expressed, and whether he shared in that feeling.

JB: Which Africa would you be thinking of? Are you thinking of Senegal or are you thinking of Freetown? And if you are thinking of any of these places, what do you know about them? What is there that you can use? What is there that you can contribute to? These are very grave questions. I don’t think that the void is absolute or that no bridge can be made. But we’ve been away from Africa for four hundred years and no power in heaven will allow me to find my way back.

Warren observes that some young, black voter registration activists from the North admired the purity of expression of semi-literate, Southern black farm workers.

JB: I would really agree with that. I’ve seen some extraordinary people just coming out of some enormous darkness. And there is something indescribably moving and direct and heroic about those people. And that’s where the hope, in my mind, lies. Much more than in someone like me who was much more corrupted by the psychotic society in which we live.

I have the feeling that the difference between the Southern white sharecropper and a black one is in the nature of their relationship to their own pain.RPW: This impulse is a very common one in many different circumstances though. You will find many white people romanticize some simpler form of life—the white hunter in the far west, or the American Indian or even the Negro.

JB: Or the worker.

RPW: Or the worker. This is an impulse of many people who feel we live in a complicated world, which they don’t quite accept, don’t want to accept, and turn to some simpler form of reality.

JB: I’m not so sure it’s simpler, though. I’m not convinced that some of those old ladies and old men I talk to down South—I know they aren’t simple. They are far from simple. And the emotional and psychological makeup which has allowed them to endure so long is something of a mystery to me. They are no more simple, for example, than Medgar Evers was simple. There was something very rustic about him, and direct, but obviously he was far from a simple man. My own father, who was certainly something like those people, was very far from being a simple man.

Warren asks about the possibility of political solidarity between black and white sharecroppers in the South.

JB: I have the feeling that the difference between the Southern white sharecropper and a black one is in the nature of their relationship to their own pain. And I think that the white Southern sharecropper, in a general way in any case, would have a much harder time using his pain, using his sorrow, putting himself in touch with it and using it to survive, than a black one. And there’s a level of melancholy, and even tragedy in Negro experience, which is simply denied in white experience. I think this makes a very great difference in authority, a difference in growth, a difference in possibility. The Negro is not forbidden, as all white Southerners are, to assess his own beginnings. He may find it impossible or dangerous or fatal to do so. But a white Southerner suffers from the fact that his childhood, his early youth, when his relationship to black people is very different than it becomes later, is sealed off from him and he can never go back, he can never dig it up, on pain of destruction, nearly. This creates his torment and his paralysis.

RPW: Some Negroes in Mississippi and Alabama hold out hope for this understanding, for the rapprochement between the Southern poor whites, the sharecropper type, the laborer, and the poor Negro.

JB: Well I don’t see much hope for it because, in the first place, the labor situation is too complex and too shaky. All workers in this country are in terrible trouble. Not enough jobs. And the jobs that exist are all vanishing. And this does not make for good relations between workers, as we all know.

Warren asks if the leadership of the civil rights movement has become more centralized or less effective.

JB: For the first time in the history of this struggle, the poor Negro has hit the streets, really. And it has changed the nature of the struggle completely. Pressure is being brought to bear by the people in the streets, especially by the poor and by the young, so that movement leaders are always in a position of having to assess, very carefully, their tactics. If the people feel betrayed, you’ve lowered their morale and then opened the door on a holocaust. I think that the Negro in America has reached a point of despair and disaffection. People talk about certain techniques being used that are destroying the goodwill of white people. But nobody gives a damn any longer about the goodwill of people who have never done anything to help you or to save you. Their ill will can hardly do more harm than their goodwill. And this is a very significant despair.

RPW: Yet you want to avoid a holocaust?

JB: Oh, indeed. We want to avoid a holocaust. But, you see, that’s not simply in the hands of Negro leaders. That’s in the hands of the entire country. If you have people up in the United States Senate filibustering about whether or not you are human, then obviously you are going to have a reaction in the streets.

So the primary responsibility would be to convey to the people, whom one sort of helplessly represents, that they are not helpless.RPW: Do you follow the line of thought that Dr. Kenneth Clark takes that Dr. King’s nonviolent method in the South has some merit but is inapplicable in the North?

JB: Yes. I’m afraid I’m forced to agree with that. Negroes in the South still go to church, some of them. And Negroes in the South, which is much more important, still have something resembling a family around which you can build a great deal. But the Northern Negro family has been fragmented for the last thirty years, if not longer. And once you haven’t got a family, then you have another kind of despair, another kind of demoralization, and Martin King can’t reach those people.

RPW: But he doesn’t know he can’t reach them?

JB: Martin does know it. He can’t abandon them, either. And it’s not that his influence is absolutely negligible. No, he is still a national leader and an international figure.

RPW: He can pack a hall in Bridgeport.

JB: Well, he can pack a hall in Bridgeport but it depends on what you are packing the hall with. The boys in the poolroom stay in the poolroom. And it’s more important to reach them and do something about their morale. I’m not blaming Martin for this; it’s not his fault at all. But to reach them is really very difficult. Malcolm X can reach them. Those kids are not Christians, and it’s very hard to blame them for not being Christians, since there are so few in this Christian country.

The differences between the North and the South were really evident when the chips were down. They had different techniques of castrating you in the South than they had in the North, but the fact of the castration remained exactly the same, and that was the intention in both places. And, furthermore, it is impossible to be separate but equal. Because if you are equal then why must you be separate? It’s that doctrine which has created almost all of the Negro’s despair and also the country’s despair. So I think that the instinct to destroy that doctrine is quite sound.

RPW: Separate but equal?

JB: Yes, that’s right. It’s really an attack on the white man’s assumption that he knows more about you than you do, that he knows what’s best for you, and that he can keep you in your place for your own good and also for his own profit.

RPW: What is the responsibility of a Negro, as you read it, to establish equality or justice? As you see, some of the white man’s responsibilities are glaringly apparent. What responsibilities does a Negro have?

JB: One has to take upon oneself a very hard responsibility, and it is something you do with the young people. It has to do with a sense of their identity, a sense of their possible achievements, a sense of themselves. For this, one has to take upon oneself the necessity of trying to be an example to them, to prove something by your existence. Part of the problem of being a Negro in this country is that one has been beaten so long, and been helpless so long, one tends to think of oneself as being helpless. So the primary responsibility would be to convey to the people, whom one sort of helplessly represents, that they are not helpless. And that if they are not helpless, then they must try to be responsible, and to create a leadership out of these boys and girls in the streets, which indeed is happening. I think it’s our responsibility, as their elders, to bear witness to them and to take risks with them. Because if they don’t trust their elders then we’re in trouble.

RPW: Well, I’m going to ask a question now that probably has no answer. How many Negroes read your books?

JB: (laughs) Well it’s an impossible question to answer. But I do know this, that my brother, who lives in Harlem, says that whores and junkies and people like that steal the books and sell them in bars. There have been a lot of hot things sold in Harlem bars but I’ve never heard of hot books being sold in Harlem bars before. So I gather that means something.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Free All Along: The Robert Penn Warren Civil Rights Interviews. Used with permission of The New Press. Copyright © 2019 by Stephen Drury Smith and Catherine Ellis.