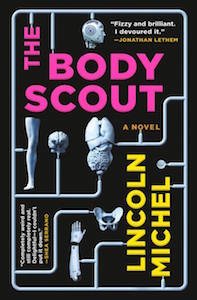

Recently while cleaning up my computer files, I found the document I used to write the first draft of what would become—many years and drafts and frustrations later—my debut novel, The Body Scout. I didn’t have a title back then. I didn’t have any epigraphs picked out either. So instead at the top of the page I typed: science fiction body horror baseball noir novel.

To a certain degree I was being cheeky—we live in a “genre-bending” era, so how many can I bend together at once?—but I was also giving myself genre as guiding lights. Here are the traditions I wanted to guide me. Here are the conversations I wanted to respect, subvert, steal from, echo, and join. Whether I was successful or not is up to the reader to decide, but I do feel I hit those notes as best I could. The novel has a science fiction setting, noir tone, and body horror set pieces. Oh, and also some weird baseball games.

I spend a lot of time thinking about genre. Maybe too much. I teach speculative fiction classes in MFA programs, publish in both “genre” and “literary” magazines, and have co-edited a series of anthologies that mix writers of different genres. For me, genre is one of the most invigorating parts of literature. Something one could study for a lifetime.

But “genre” is also a funny, fraught thing. On the one hand, genre labels are highly useful terms that almost everyone can explain… often in minute detail. If you’ve got a few hours to kill, ask a SFF fan to delineate the differences between “cyberpunk” and “steampunk” or “epic fantasy” and “grimdark.” On the other hand, the scars of decades of genre wars, two-way gatekeeping, and general snobbery leads many people to throw up their hands and say “It’s all just marketing! Art doesn’t need labels!”

I get this impulse. I’m on the record as someone who thinks the distinction between “literary fiction” and “genre fiction” is a false one. But while it’s important to break down the barriers of snobbery between genres, I don’t think we should flatten them to mere marketing labels. Genres are vital artistic traditions, with their own aesthetic histories, concerns, and modes.

So in an era when people increasingly want to dismiss genre labels, I’d like to argue we actually need them more than ever. That they can be extremely generative and rewarding to think about, at least if we understand them in the right way.

*

Genre as an Artistic Conversation

Here’s a metaphor. Imagine literature is party in a grand estate. Countless people seem to be there, and more keep arriving. It’s loud and chaotic and exciting. Within this party, different groups of people cluster to talk. Some in fancy costumes chat in the rose garden. Others mutter in the library or laugh together beside the graveyard plot. In each of these different conversations, people expand on each other’s thoughts, rebut, debate, elaborate.

This is how I like to think of genres. As different literary conversations, ones that stretch back in time and include not just authors but critics, publishers, and readers. When a critical mass forms—and the conversation is large enough—we have a genre. If the conversation is small and scattered, it might be only a subgenre or style. One can engage in these literary conversations to whatever degree one wants. Hunker down in an armchair in one spot for a career or hop around dipping into different conversations as your interests change.

As with any ongoing group conversation, there are sometimes barriers to entry. In-jokes develop. References. Special topics of concern. People who stumble onto the conversation might, at first, be lost. (Typically, it’s good to listen for a while before speaking in literature as in life.) And not every conversation will be of interest to every person. But that’s as it should be. Literature is an infinite and varied place.

This is how I like to think of genres. As different literary conversations, ones that stretch back in time and include not just authors but critics, publishers, and readers.This is also why I love genre. Writing in a genre (or subgenre or sub-sub-genre) is a chance to join a conversation. A tradition. A chance to listen to others, and then add your own voice. To figure out what you can add to a conversation that stretches back through time.

Much of the pleasure of genre fiction is in understanding what is being homage, subverted, or remixed. That is, in understanding the conversation. Take, for example, recent works by Black authors like Victor LaValle and N.K. Jemisin that confront and subvert the racist legacy of Lovecraft in “cosmic horror.” One could read The Ballad of Black Tom or The City We Became without being familiar with the conversation of “cosmic horror,” but I think you’d get more out of them if you were.

So why is it that people fight so bitterly about genre? And why are so many so quick to dismiss the concepts entirely? While there are many reasons, I think a lot comes down to the fact that the definitions are contradictory, confused, and often flat out false.

*

What Genre Isn’t

The first Google results for “what is genre fiction” define it as a synonym for “popular” or “commercial” fiction. This as opposed to general fiction or literary fiction. This bears little relation to reality. Most books of any label are not popular, but no one would argue that, say, a novel about orcs fighting elves isn’t genre fiction if it only sells 100 copies. At any given point of time, some genres are popular (mysteries and thrillers dominate today) and others not (Westerns aren’t exactly thriving). And so-called “literary fiction” is often quite popular! The reason publishing pays huge advances to Sally Rooneys and Jonathan Franzens instead of steampunk novellas or swords and sorcery tetralogies is because the former sell a lot more books.

Another common yet, I think, incorrect definition is that genre fiction is “plot-driven” and literary fiction is “character-driven.” It’s a strange claim to make when so much genre fiction is powered by series of books with recurring characters and fan fiction flourishes because readers feel such deep connection to genre characters. Okay, you might say, genre books have popular characters, but literary fiction delves more deeply into character aka the complexities of human consciousness. Impossible to prove, but much of what is published as literary fiction—for example a lot of my favorite postmodernist and surrealist literature—has little interest in character of that kind either. Meanwhile, popular literary fiction these days is tightly plotted and plenty of genre fiction is not.

Other claims—such as that genre fiction is inherently formulaic while literary fiction is innovative—can be dismissed by a perusal of the new releases at any bookstore. But let’s put the genre/literary debate aside a second and discuss how different genres are defined.

*

The Prescriptivist Approach to Genres

What separates fantasy from science fiction? Romances from Westerns? The most common way to define these is what I’d call a “prescriptivist” approach. (In linguistics, “prescriptivists” define words and grammar by how they think people should use them while “descriptivists” define them by how people actually use them.) Genre prescriptivists describe genres as clearly delineated categories, and then put authors in those boxes without worry about, say, an author’s influences or intents. Any book about impossible magic is fantasy, any book about possible technology is science fiction.

Often there is a sense that these are almost Platonic, immutable categories in which literature that predates these modern terms can be neatly shuffled into: ancient myths (e.g., The Iliad) are deemed fantasy, novels of manners (e.g., Jane Austen) are rebranded as romances, and so on.

This kind of definition has the pleasure of seeming scientific. And there’s an additional pleasure for genre fans tired of gatekeeping to get to declare that much of what is published as literary fiction is “really” not. One Hundred Years of Solitude is “really” fantasy. Infinite Jest is “really” science fiction. Normal People is “really” romance. Etc.

*

A Descriptivist Approach to Genres

The problem with the above approach is that it doesn’t bear much relation to the actual aesthetic traditions and histories of these genres nor how they are used in the real world by critics, fans, and writers. For example, what does it mean to declare that a postmodernist like Donald Barthelme is “really” a SFF writer? It doesn’t give us insight into his influences, and it also doesn’t line up with the reality that he was published within the ecosystem of “literary fiction”—where he remains one of the most influential short story writers—while making little impact in the SFF ecosystem of awards, magazines, and authors.

One could imagine an alternate history where postmodernists like Barthelme or magical realists like Marquez were ignored by literary fiction ecosystem and thrived in the SFF one. Where they won Nebulas and Hugos and published in Asimov’s instead of The New Yorker. But in that alternate history, the trajectory of both literary fiction and SFF would be different.

While a prescriptivist approach flattens work, a descriptivist approach—examining the actual history and usage of the terms—can expand our understanding.If we try to understand genres not by imposed definitions, but by an examination of the actual ecosystems, histories, and conversations within them I think we learn a whole lot more. And I also think what we see is more interesting. Rather than fixed categories, we see genres as living breathing things. Ones that are always changing and transforming.

To me, it’s fascinating to compare, for example, the modern SF focus on logical worldbuilding with the freewheeling and often nonsensical worlds of SF classics like The Martian Chronicles or Cat’s Cradle. We can also see how genres might die, or at least fade into something more like a “style.” (See: Southern Gothic.) And why it’s unsatisfying when someone tries to invent a genre by grouping together works that have little overlap in readership, approaches, or history. (See: “hopepunk.”)

We can also see how genres grow into different conversations in different cultures. In the Anglo sphere, the great influence of Tolkien and similar authors meant that “fantasy” has become largely synonymous with magic-infused settings, grand quests, and so on. But over in France, the “fantastique” developed as a quite different genre that blends elements of what the Anglo sphere calls horror, magical realism, and fantasy together.

While a prescriptivist approach flattens work, a descriptivist approach—examining the actual history and usage of the terms—can expand our understanding.

*

The Literary Fiction Problem

It makes sense that “literary fiction” causes much of the problems in the genre debates, because it really is a confused term. “Literary fiction” is used as a qualitative description for high artistic merit—this is why some critics insultingly declare a work “transcends genre” to deserve the label—but it is simultaneously a label for a genre of work with varying quality. No one would say your average MFA grad novel is of high artistic merit, but they still tend to get the label “literary fiction.” It’s understandable to be rankled at this.

Even if we dismiss the qualitive meaning, the term is strange. There is a clear ecosystem of literary fiction—a set of awards, magazines, authors, and such—and thus a distinct conversation. Yet what unites Kafka, Morrison, Bernhard, Marquez, Cusk, Cheever, Erdrich, Calvino, and Adler (to pick a few at random)? Nothing in terms of setting, tropes, styles, or modes. I think the best you can do is say that most literary fiction centers style and form in the way that crime fiction centers crime or romance centers romance. But that’s debatable and I can think of plenty of counterpoints.

This topic could take up a book, so all I can say is that it would probably best if we could figure out how to divorce the “quality” definition from the supposed genre. For me, at least, “literary” is a descriptor that can be applied to any genre. There is literary science fiction and literary horror as much as there is literary domestic realism. But this is a longer argument for another time…

*

Genre as Generative Force

Okay, so I’ve futzed around with the possible definitions of genres, but what is the point? Why do we need labels anyway? Well, I’m a writer and so I do think words are useful. I think that if we understand terms and labels, we can actually think deeper about what they describe.

And I know a paucity of genre labels does not increase understanding. In my “literary fiction”-focused creative writing classes, genre labels were almost never used. When they were, it was to lump vast swaths of unrelated literary traditions, modes, and styles into a handful of boxes. (Anything that involved some unreal elements was called “magical realism.” Anything that was funny was “satire.”) The lack of genre terms led to more confusion than understanding.

When I wrote science fiction body horror baseball noir novel in my document I was signaling to myself what conversations I wanted to be involved with.But I’m mostly concerned with what is generative for writers. As always, the answer to that is whatever works for the individual writer. For me, at least, I find genres to be extremely productive to think about. They are generative in the way that poetic forms or Oulipian constraints can inspire writers to greater creativity.

When I wrote science fiction body horror baseball noir novel in my document I was signaling to myself what conversations I wanted to be involved with. So I set to work. I reread my favorite books in those genres and thought about what gaps I saw. Where I could add something. Far from being constraining, these genre labels made my brain buzz with ideas. What is a detective character in baseball setting? What is a femme fatale seen through a science fiction lens? What twist will conjoin the central crime with body horror? The genres helped inspire the characters, setting, and plot.

My resulting novel, The Body Scout, would simply not have existed without this generative process. Without thinking of the literary conversations, the genres, that I wanted to speak to and listen to. Or at least, the results would have been something else entirely.

So I say think of genres as artistic conversations. Join the ones that interest to you. Listen to them. Jump from this one to that one. Then add your own voice in whatever role you want.

______________________________________________________________

Lincoln Michel’s The Body Scout is available now via Orbit.