My young husband and I were too square for the “Woodstock” festival the previous summer. But now, when Tim Buxton’s childhood friend, Barbara Sproul, invited me to borrow the cabin she rented in the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony for which the town of Woodstock, New York was originally known, I went. “Wake Robin” was just across the valley from the spacious farmhouse leased by Philip Roth, Barbara’s partner for what would come to be most of that decade, and it would be there, in sharing the quiet rhythm of their life together, that I could begin to sense the new shape of my own.

Weeks earlier, Tim and I were barely into our Operation Crossroads Africa summer program as co-leaders of a group of American and Canadian student volunteers assigned to upcountry Ghana when an unspecified fever initiated a decline that dead-ended seven days later. Late the night before, I’d brought Tim in to the Wenchi Methodist Hospital, where he was denied admission by the same Medical Officer who then pronounced his death thirty hours later. Here is that European doctor’s entire report, dated July 10, 1970:

Patient was seen first on the 9/7/70: 2 am. He was depressed, made an impression of exhaustion and was suffering from sleeplessness. Physically nothing abnormal could be found. Cause of Death: (Suicide: cutting of the big vessels in the neck.)

Barbara knew Tim better than anyone, certainly better than I did, and I welcomed her calm descriptions of the frequent conversations she and Tim had shared about the several suicide attempts Tim’s father had made, and the one her own had succeeded at. “Tim didn’t get it about suicide,” she insisted to me, and while of course I certainly didn’t get it either, her authority gave me permission to try understanding and accepting his death, more sympathetically, as a mystery. Whatever that meant!

I possessed no personal language for comprehending and embracing mystery the way Barbara and Tim did. She was a protégée of Joseph Campbell and had already assembled a collection of creation mythology. She too had studied at Union Seminary, and though she would never take up Christianity except as a scholar of it, she could help me see what Tim studied and believed.

On my own parallel track I’d immersed myself as a student of French literature’s passionately self-destructive Romantic poets, and tried to learn how to interpret their madness. Purely domestic in my own habits, I’d worked to appreciate—on the page—the abandonment of self that enabled their self-discoveries. With access to Tim’s own studies in religion and philosophy I felt provoked to imagine possessing a greater intelligence than my own. Whatever that meant.

The Savage God: A Study of Suicide by A. Alvarez was published in Great Britain within months of Tim’s death, and while nothing could have been more shocking for me to read, I read it twice. The book opened with the example of an “unusually sweet-tempered” schoolteacher:

One day at the end of a lesson, he remarked mildly that anyone cutting his throat should always be careful to put his head in a sack first, otherwise he would leave a terrible mess. Everyone laughed. Then the one o’clock bell rang and the boys all trooped off to lunch. The physics master cycled straight home, put his head in a sack and cut his throat. There wasn’t much mess. I was tremendously impressed.

Alvarez concluded this anecdote, “The master was greatly missed, since a good man was hard to find in that bleak shut-in community. But in all the hush and buzz of scandal that followed, it never occurred to me that he had done anything wrong.”

The Prologue to The Savage God concerned the famous suicide of Alvarez’s friend, the poet Sylvia Plath. I’ve seen a recent statement by Alvarez that he rebukes himself to this day for not recognizing that she was ready to kill herself. “I failed her. I was thirty years old and stupid,” he says, and while I know what he means—I was twenty-six and stupid—the truth is, unlike Alvarez, who had by then made a failed attempt on his own life, I had no idea what it took to be smart enough.

Around that time I also read the novel L’ Amante anglaise by Marguerite Duras, a stunning deciphering of the logic of madness in the form of a police interrogation of a confessed murderer. A haunting recognition by the accused has stayed with me ever since, when the protagonist understands, “Je n’étais pas assez intelligente pour l’intelligence que j’avais . . .” —not smart enough, she means, for the clinical madness attributed to her—because I wonder whether Tim’s not being intelligent enough for his own intelligence—his self-diagnosed disequilibrium—became another reason to kill himself. In the Duras novel the confessed murderer wished to be completely intelligent, but she realized that in the face of her own death one day her only consolation will be her knowledge that she wasn’t intelligent enough for her own intelligence.

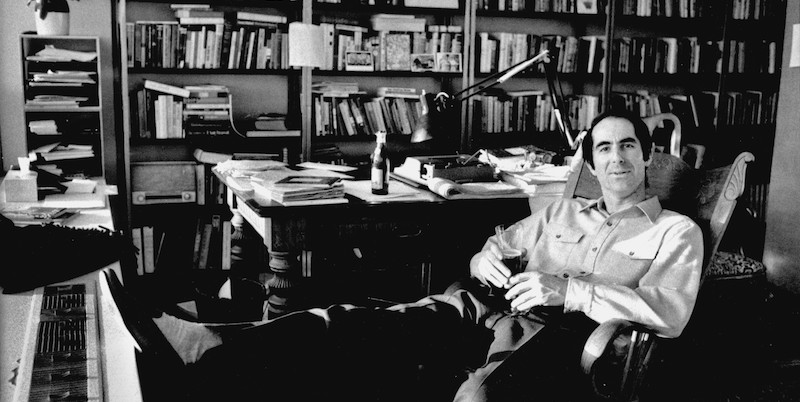

But that season’s major publishing event was Portnoy’s Complaint, and it was such a literary and commercial tour de force that Philip felt forced to seek refuge in the countryside from the strangers who accosted him—“Hey, Portnoy!”—on the streets in the city. In Woodstock, he and Barbara took long daily walks together, for which Philip kindly invited me to come along. On those walks and during the meals we regularly shared I felt adopted by him, like a rescue pet, and I fed on his jokes like a Continuing Ed student assigned to re-learn laughter.

During those Woodstock mornings in Barbara’s “Wake Robin” cabin I devoured the four books that Philip had published by that time, and started in on his reading list of the American classics he was surprised to see I didn’t know. At least I was already familiar with Flaubert’s famous prescription for the writing life, from a letter he wrote on Christmas Day, 1876, nine years after Madame Bovary. Philip often quoted, “Be regular in your life and ordinary as a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work,” advice Philip both practiced and preached so fervently that it felt like religion.

Beyond being childhood friends, Barbara and Tim were college lovers before becoming graduate students together both at Union and in a parallel program at Columbia. I’d been introduced to her by Tim in the completely white garden apartment in midtown Manhattan, the home from which Barbara commuted to college at Sarah Lawrence. Her older brother was killed in a car accident, and her parents had ruined each other with their vengeful divorce. Barbara’s apartment was adjacent to her father’s, where, when she turned twenty-one and he decided his life was over, he ended it.

Philip had declined to meet Tim, so he was curious to know why I hadn’t had the same feeling about meeting Barbara. Over dinner on the screened porch of that Woodstock farmhouse I answered that it was because it was immediately clear that Barbara was in a different category from me. She was then still an undergraduate when she showed me the obscure varieties she’d already amassed of creation mythology—creation mythology!—for the collection that would later become her scholarly work Primal Myths. I told Philip there was no contest since I couldn’t compete with that level of distinction—“Nor could Tim with you, incidentally!”—but Philip held his ground. I was glad at least that his admitted possessiveness of Barbara, relative to Tim, hadn’t extended to me.

As their guest in the steadying worlds that Barbara and Philip were creating together, I felt both sheltered and shielded. When they brought me along to gatherings, I was briefed. I was cautioned ahead of a literary soirée in New York to avoid a particularly acquisitive writer who “never sees where he ends and you begin” and always takes advantage. I felt protected. I felt safe.

When Philip read to Barbara sections of what would become his novel The Professor of Desire, she chided him affectionately, “Don’t you people make anything up?” He laughed it off, but he remained irritated by the persistent speculations of literary critics analyzing the overlap between his fictions and the private life that was increasingly public.

So, yes, Barbara was the “Claire” of Philip’s novella The Breast and the “Claire” of the novel The Professor of Desire. When Philip’s “Philip” character, David Kepesh, describes the “Barbara” character—Claire—as “the most extraordinary ordinary person I’ve ever met,” he is describing “prudent, patient, tender” Barbara. Although she left Philip over her own desire to have children eventually—and his determination not to—they remained closely connected ever after, until the night of Philip’s death fifty years later, when Barbara was with him.

I suppose it looks inevitable that, during these early months when I watched Philip at work, I too discovered the urge to write. I had a story to tell.That is, it’s only an ironic coincidence that The Professor of Desire is dedicated to Claire—Claire Bloom—whom Philip later married, disastrously. I only met Claire once, over lunch, but in a phone call soon after that wedding Philip’s only—ominous—comment to me was, “Well, I did it.”

The point is that nothing mattered more to the man I knew than to achieve the oeuvres Flaubert defined as violent et original. He did this time and again, and although Philip consecutively evaded the ultimate bourgeois creation of a conventional family life, with Barbara I saw him come close.

*

I suppose it looks inevitable that, during these early months when I watched Philip at work, I too discovered the urge to write. I had a story to tell, and while untrained in composition, I’d been immersed in the theatrical dances devised by Martha Graham, a dynamic choreographer whose themes were literary, in fact. Within the literal mechanics of choreography, the effect is realized by means of contiguous phrases of movement rising and falling on the contraction and release of a breath. I could see that Martha Graham’s classic technique was organic the way good writing is alive when it moves across the page. I began to believe that from my own choreography in high school and college and beyond, it was possible that perhaps I already understood a few of the basics.

Of course Philip’s example meanwhile made clear that, no matter what I might know about dance, I still had everything to learn about writing. More concretely, I could observe in Philip’s daily routine the value in spending twice as much time reading as writing. One weekend during those early months, I was visiting Barbara and Philip at the property he’d recently bought, shifting their base from Woodstock to Warren, Connecticut. It was on their couch by the fireplace that I read in the New York Times Book Review a featured review of a new biography of Virginia Woolf by her nephew, Quentin Bell. I’d had only the slightest knowledge of Virginia Woolf’s writing from reading To the Lighthouse, too early, as an eighth grade summer reading assignment, so this chance introduction was an epiphany. That afternoon I started with her first novel, The Voyage Out, and proceeded to read her straight through.

For the rest of his life I amused Philip by crediting him with teaching me how to read and, by extension, to write. Among his many actual students I knew I wasn’t alone, just as I became only one of a legion of fans who would forever answer, when asked to name their favorite writer, “Virginia Woolf!” It was absurd for me to imagine myself a talent, but Philip encouraged me nonetheless. And while it was many months before I showed him my first effort—to which he awarded the title The Child Widow like a gold star—I’d already benefitted from its therapeutic value by writing about the loss that defined me.

With Philip’s validation I dedicated myself to his daily routine of alternating hours of writing with twice that many hours of reading. Though still assuming the way to repair my ruptured life was to go back to school and trade in my two degrees in French for one in the recently established field called American Studies, I was suddenly also able to imagine my new identity as an apprentice writer. Each night I found myself actually looking forward to the day ahead, which both helped get me to sleep and got me up in the morning. I felt alive, and was able to sense that a writer’s life could be a way of staying alive. Could this be what they meant by vocation?

I still value the lesson I learned from Philip on one of those peaceful afternoon walks back in Woodstock. After spending the day reading Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet for the first time, I thanked Philip for the recommendation. I was flattered by his taking my own education seriously, and told him I’d found Rilke’s mentoring advice helpful.

Although Rilke’s formal and somewhat stuffy language was a barrier to me, I felt I knew what Rilke meant when he advised the young poet:

Ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple ‘I must,’ then build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse.

I told Philip I had been witnessing this in him without yet daring to propose the question to myself, but I was definitely on the lookout for some necessity to build my life around. I said Rilke spoke to me more directly with this:

The quieter we are, the more patient and open we are in our sadness, the more deeply and serenely the new presence can enter us, and the more we can make it our own, the more it becomes our fate.

I honestly didn’t feel very “patient” or “open” in my sadness, but I could appreciate that, with this new routine, my life was already becoming quieter. I was coming to believe it was possible to live according to Rilke’s exhortation:

Live the questions now. Perhaps then someday in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

In the sometimes oppressive isolation of “Wake Robin” I’d been searching for answers and finding none to fit my questions about Tim’s violent dying. But I gradually felt persuaded to let myself simply settle into the nourishment of a daily rhythm. Just by sleeping and eating better I was already restoring my own health, and I’d been able to gain back a little of my vanished weight. There were quiet dinners with Barbara and Philip at the farmhouse and frequent raucous dinner parties on the weekends with their New York friends who came up from the city to their own country houses. Philip’s well-chronicled time in the Army yielded standup comedy routines that I found hilarious, such as the time he entertained the table by mimicking the language of the fellow soldiers who inserted “fucking” between the syllables of most words. Like what? It can still make me laugh to remember him pointing to a casserole of baked eggplant and tomatoes and zucchini and saying “Like rata-fucking-touille.”

We three continued our walk along the familiar path and arrived at the little wooden bridge across a narrow stream. On this particular beautiful afternoon the air was still, as if poised, and though I know it’s melodramatic to call this moment a crossing into literary consciousness, that’s how it felt at the time.

In Rilke’s definition of a good marriage “each partner appoints the other the guardian of his solitude, and thus they show each other the greatest possible respect.” While this obviously wasn’t the case with Tim or I’d have been clued into the depth of his solitude, I needed to believe in the possibility.

At the table by the window in “Wake Robin” I’d read this next passage so many times that I was able to quote it word for word:

And this more human love . . . will be like that love which we are straining and toiling to prepare, the love which consists in this, that two lonely beings protect one another, border upon one another and greet one another.

In reciting this passage for Philip and Barbara I believed in their having found “this more human love” with each other. And while acknowledging in myself an unrequited yearning for a bond of this dimension, I was also alert to the jolt of joy I was experiencing, despite my fears, in redefining myself.

Rilke’s prescription for lonely beings provided an uplift so alluring that it was as if the toxic smoke that infiltrated my lungs at the ritual cremation I’d commissioned on a hilltop in Ghana could be forcefully enough expelled as to become a vapor trail. Maybe I even looked up to the sky, expecting to see my breath escape, and evaporate.

And here’s what I mean about what I really learned that day, as I stood there reciting Rilke’s “two lonely beings protect one another, border upon one another and greet one another,” still ignorant of—but not immune to—the essential, discernible borders between sentimentality and subtlety, between pessimism and irony.

Philip’s purpose wasn’t to contradict me when he stopped me with his deadpan gaze.

But I felt myself being reeled back to reality when he gently asked, “And then what? Go bowling?”

___________________________________________________

An adapted excerpt from Alexandra Marshall’s The Silence of Your Name: The Afterlife of a Suicide, forthcoming from Arrowsmith Press on November 7, 2021.