Under the bright lights of the finished show, a performer need only reflect the electric candle power that is directed upon him. But in the dark and dirty old training rings and in the makeshift cages, whatever light is generated, whatever excitement, whatever beauty, must come from original sources—from internal fires of professional hunger and delight, from the exuberance and gravity of youth. It is the difference between planetary light and the combustion of stars.

–E.B. White, “The Ring of Time”

*

In college, my father was a sculpture major, welding straw-sized rods side by side to form flat planes, fixing these faces together into three-dimensional abstractions, birds in flight. A childhood injury—he got hit in the head with a thrown horseshoe—left my father with moderate nerve damage in his hand, and he’d only realize the welding torch was burning him when he’d smell flesh. I sometimes imagine what meditative, maddening effort it must’ve taken to join these thousands of individual metal sticks, one by one, making them into something.

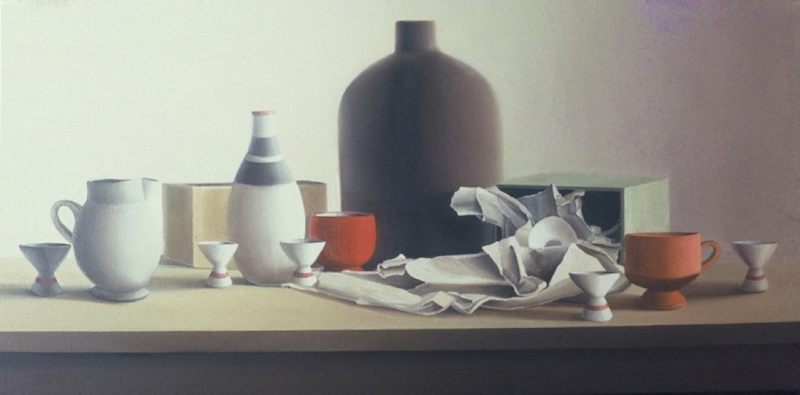

By grad school he’d shifted to painting and drawing. He idolized Morandi—the way he could paint the air and atmosphere around forms that he saw as intimate, anthropomorphic, groupings—so he created still-lifes that were family portraits in disguise. His mother was the large, dark urn, the dominant presence in his world.

“Bird Form” (with the artist), 1968; 1⁄8” Welded steel rods, 80 x 94 x 47 in

“Bird Form” (with the artist), 1968; 1⁄8” Welded steel rods, 80 x 94 x 47 in

Books were another chosen subject of Barry Nemett’s early work—still-lifes transformed into cityscapes, landscapes, and metaphors for personal get-togethers—and he impressed upon me his passion for literature as much as visual art. When I was four, and mentioned a vague interest in insects, Dad busted out Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” remembering only the bug, forgetting the pure existential nightmare. It was a misstep on his part.

But sometimes he knocked it out of the park. I was big into Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little, so Dad took a shot and read me E.B. White’s essay, “The Ring of Time,” a voyeuristic account of circus performers honing their craft during off hours.

“Book Composition after ‘The Great Pine Tree’ by Paul Cezanne,” 1972, Charcoal on paper, 48 x 96 in, Collection of John Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“Book Composition after ‘The Great Pine Tree’ by Paul Cezanne,” 1972, Charcoal on paper, 48 x 96 in, Collection of John Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The core subjects of the essay are an elder horse trainer in “high heels, which probed deep into the loose tanbark and kept her ankles in a state of constant turmoil”; and her counterpoint is a younger stunt rider, “a girl of 16 or 17 . . . barefoot, her dirty little feet fighting the uneven ground.” The essay is about practice, simultaneously mundane and exalted:

As soon as [the young girl] had squeezed through the crowd, she spoke a word or two to the older woman, whom I took to be her mother, stepped into the ring, and waited while the horse coasted to a stop in front of her. She gave the animal a couple of affectionate swipes on his enormous neck and then swung herself aboard.

I didn’t understand all of the essay, still don’t, but I knew it was beautiful. I projected myself onto that steed and realized this man—this author equally at home with talking pigs and mice—could put together words in an extraordinary, adult way; that language was not explicitly meant for this, maybe, but through some cunning trickery he’d coopted words to say something more than themselves, something mysterious and musical and alchemical that demanded questions I could not yet formulate.

As if on cue, White answered: “As a writing man, or secretary, I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost.”

I consider myself “a writing man,” and though I don’t quite feel White’s maudlin sense of duty for every worldly detail—calm down, buddy—the call to safekeep isn’t far off.

“Gathering 6,” 1982, Charcoal and pastel on paper, 28 x 120 in

“Gathering 6,” 1982, Charcoal and pastel on paper, 28 x 120 in

Dad often told me about his thrill at becoming a father. Initially, he and my mother planned to remain childless, world travelers, happy. He was beginning to exhibit more broadly, in SoHo art galleries and museum biennials, garnering reviews in Arts Magazine, The Village Voice, Soho News. He scored a Fulbright to Spain and then a Ford Foundation grant to Italy, which is where I was conceived.

“I decided right then that I didn’t care about any of that,” my dad has told me, meaning his career. “I just wanted to be a father.” Which is an incredibly gracious thing for a father to say to a son, but most likely a lie. I’m not sure what age is normal for a kid to worry that you’ve derailed your parents’ dreams, but his preemptive strike against such thoughts was invaluable to my young mind.

Still, though: really?

Success is a tricky thing, and if he was truly tasting it back in the late 1970s and then temporarily chose to cut himself off from the fancy NYC art world in favor of homebound, sleepless nights in Baltimore, working small . . . did he really not care? Does he now?

In 1981, he created a collage-like painting called “Seasons,” dedicated to my first year of life, a vertical 84” x 46” work comprised of many small pages depicting trees seen from my bedroom window. Next was his “Gatherings” series: peaceable kingdoms of overlapping animals like some bestial cuddle puddle. Not that his pre-child paintings were R-rated, but I wonder if he changed his work to suit his son, or else did I change his work intrinsically and he simply allowed this shift to happen?

Dad’s wasn’t some vague, foreign, romantic dream of “being an artist”—the volatile, tortured genius, the mad midnight frenzies—but his was a late-night practice. Putting pieces and pages together, side by side, one after the other.

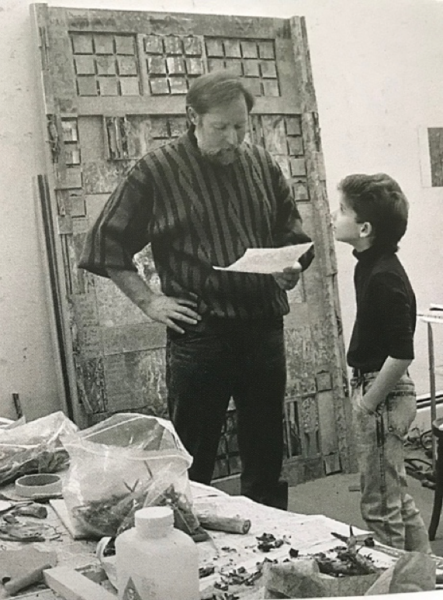

Adam Nemett and his father Barry collaborating on the set for Adam’s feature film The Instrument (Magister Productions, 2005)

Adam Nemett and his father Barry collaborating on the set for Adam’s feature film The Instrument (Magister Productions, 2005)

This was art, for me: diligence and discipline, derived from passion. As E.B. White said of his teenage circus star, “I somehow got the idea she was just cadging a ride, improving a shining ten minutes in the diligent way all serious artists seize free moments to hone the blade of their talent and keep themselves in trim.”

My father started writing a novel, and it took him about a decade to produce and publish Crooked Tracks, the story of a high school kid who projects himself into paintings—Edward Hopper, Ben Shahn, Sidney Goodman, Johannes Vermeer—as a way of stopping time and avoiding the PTSD of a particular tragedy. The themes are intense—death, brotherhood, addiction, love—but when I was old enough he’d read me passages and I’d just crack up at the curse words. If I remember correctly, “dumbfuck” slayed me.

He’s been a professor at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) for nearly 50 years—25 as Chair of the Painting program—and this was his office, the place I visited Dad at work, the milieu I couldn’t help but imagine for myself, the way all boys consider their father’s workplace and contend with the thought of the same fate.

Barry Nemett working on “Stone Passages: France to Italy,” 2011, Graphite on paper (with carved frame by Stuart Abarbanel), 120 x 240 in

Barry Nemett working on “Stone Passages: France to Italy,” 2011, Graphite on paper (with carved frame by Stuart Abarbanel), 120 x 240 in

“For you to rebel against me,” he’d say, when I became a teenager, “you’d have to become a banker.” And there were periods where this seemed a possibility: I got married in the depths of the global financial crisis and, desperate for independence and to prove myself a provider, I fell into a corporate job that still allowed me to write creatively.

Before that, I went to Princeton, but pined for the art school experience. So I got my MFA at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, where I began writing my novel We Can Save Us All in late 2005. Like most young writers, I’d heard romantic legends of Kerouac or Bukowski writing entire novels in a single Benzedrine-fueled weekend. For me, it was a slower plod. An iterative process. Putting pieces and pages together, side by side, one after the other.

The dozen years it took to get the novel written, revised, and published were, at times, frustrating as fuck, but in other moments, perfect. Going over and over that story, in my weird solitary way, I occasionally grasped what White saw in his circus rehearsal:

The rider’s gaze, as she peered straight ahead, seemed to be circular, as though bent by force of circumstance; then time itself began running in circles, so the beginning was where the end was, and the two were the same, and one thing ran into the next and time went round and round and got nowhere.

“View from Montecastello,” Tryptich, 2017, Gouache on paper, 83 x 67 in, Collection of Jim and Carol Trawick Foundation

“View from Montecastello,” Tryptich, 2017, Gouache on paper, 83 x 67 in, Collection of Jim and Carol Trawick Foundation

Like my father, I wrote a book that considers the nature of time—a coming-of-age tale that features the drugs of its era (in his book, booze and heroin; in mine, psychedelics and performance enhancers). And like most sons, I experienced that double-edged fear: that my book might not be as good as his; or that it might be better.

There’s a wide gulf between the creation and reception of writing or painting—the near-silent delight of an enraptured reader or museumgoer that rarely reaches the artist’s ear—compared to the immediate and, at best, electrifying response experienced by the actor, the rockstar, the comedian, the circus rider.

For the more solitary arts, you have to love the process, the practice, behind the scenes. “A man has to catch the circus unawares,” wrote E.B. White, “to experience its full impact and share its gaudy dream.” I agree.

These days, my father is as much a writer as a visual artist—his essays for Hyperallergic, like the one that inspired this article, are among my favorite pieces of writing—and he works both large and small, filling walls and endless sketchbooks.

And these days, I’m a father of two. My daughter is 17 months old, her formidable personality just developing, but I’ve begun to see my son anew. He’s four now, almost five, and is asserting his preferences. He loves books and music, like his father, because I probably surround and impress these upon him the same way my father did. He loves superheroes, and when he found out that Daddy wrote a book about superheroes he naturally asked to read it. How could I possibly explain? This is even worse than Kafka, I wanted to say.

“You can read it in about 12 years,” I told him.

I considered where he’d be a dozen years from now, the same way White projected the young circus rider as an adult wearing “hi-heeled shoes, the image of the older woman, holding the long rein, caught in the treadmill of an afternoon long in the future.”

I don’t much care if my son becomes a writer or engineer or farmer. Whatever he does, I hope he loves it, the process, the practice, the routine. I hope he figures out there’s only one audience member worth electrifying.