One week after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I received a message in English from the eastern part of the country, from an acquaintance—let’s call her Olha—in the city of Sumy. Founded by Cossacks in the mid-17th century on the banks of the River Psyol, it has since spread across a vast, flat, green landscape to become a leafy city of over a quarter of a million inhabitants, boasting universities, factories, museums, beautiful Orthodox churches and cathedrals, and a huge indoor market.

Olha’s message said:

We are rather fine comparatively to Kharkiv and Okhtyrka, and Kyiv and many other cities. Still, Sumy region is at the forefront of the battle and the street fights and air attacks happen every day. The city is surrounded by the Russian forces.

Most of all, we are extremely anxious about our brave warriors and city dwellers, but what makes many people worried is the cultural heritage of the city, especially the fate of Chekhov museum.

Last night there was a fight in the area close to the museum.

I had visited Ukraine in 2010 but it feels like another century now, another life: sightseeing in Crimea; touring tsars’ palaces; dining with a view on the Black Sea; above all, exploring the traces left by Anton Chekhov, mostly (but not only) at the end of his life. After Crimea I traveled to the far northeast, an overnight rail journey, to the Russian-speaking city of Sumy, where Chekhov spent two summers in his youth. I visited the small museum there and was warmly welcomed by its then-director, Ludmila Nikolayevna, and her assistants. They helped me with my research, and we promised to stay in touch. A few years later, when my book was published, it was Olha who helped with getting copies to the museum’s library, and we continued to correspond about Chekhov from time to time.

A view of Sumy. Photo by Alison Anderson

A view of Sumy. Photo by Alison Anderson

Chekhov spent two consecutive summers with his family in the village of Luka, not far from Sumy, in 1888 and 1889 on the estate of the impoverished Lintvaryov family, who rented them a small bungalow. In the Psyol they swam and fished and went rowing; they invited friends to stay, held concerts and readings, dined and flirted. Chekhov worked on several short stories and a play (The Wood Demon).

In his letters, he wrote warmly of his time in Ukraine, which was then a province of the Russian Empire; looking back, he said, “Abbazia (present-day Opatija, in Croatia) and the Adriatic Sea are fine, but Luka and the Psyol are better.” His brother Nikolay died of tuberculosis the second summer and is buried in the local cemetery; after the funeral, the family spent some time at a monastery in nearby Okhtyrka. Their hosts in Luka became lifelong friends; the region and its inhabitants were a source of rich inspiration for the young writer.

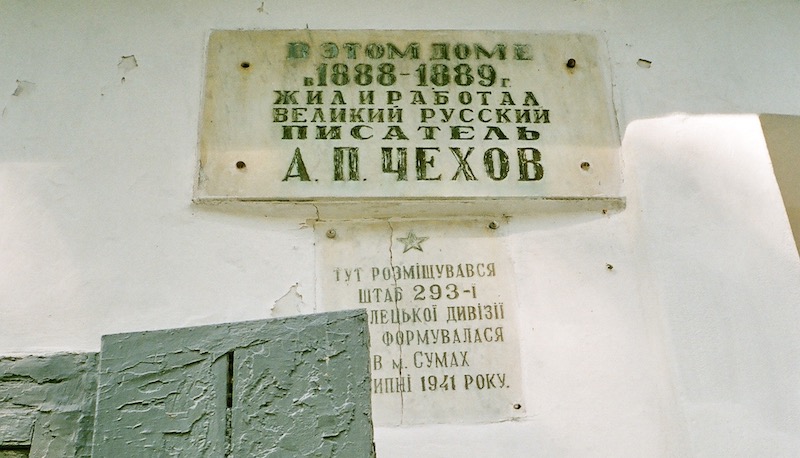

A view of the Chekhov House Museum.

A view of the Chekhov House Museum.

Chekhov is often held to be the world’s greatest short story writer, and perhaps second only to Shakespeare in terms of the number of times his plays have been adapted or produced. Not only a Russian writer, he belongs to the world. Sumy is justly proud to have played an important role in his life and to have continued to honor his legacy since 1960, the centenary of his birth, when the bungalow, converted into a school library by the Bolsheviks, was restored to its original state and became a museum.

It is set back from the road leading to the river, across from the ruined manor house; it has its own garden with irises and a gazebo and, at the time of my visit, a resident kitten. It is small—six rooms—compared to other Chekhov museums located in Moscow, Melikhovo, and Yalta, but the memories the writer took away from those incomparable summers of his youth resonate to this day beyond any borders—in the stories and plays he passed on to innumerable readers and theater-goers, including, surely, the officers and soldiers now fighting for possession of Sumy: everyone studied Chekhov in school.

“In this house, in 1888-1889, lived and worked the great Russian author Anton Pavlovich Chekhov.” Photo by Alison Anderson

“In this house, in 1888-1889, lived and worked the great Russian author Anton Pavlovich Chekhov.” Photo by Alison Anderson

I received another email message, not long after the first one, this time from a university professor in Russia who is also a friend of Olha:

I have been in touch with Sumy on a daily basis and the news has been devastating. Ludmila Nikolayevna is in Sumy, it is almost impossible to talk with her—she did not want to speak about the museum, which was in the war-zone and at this point I do not know what happened to it. I got in touch with a fellow Chekhov scholar in Moscow asking him to make a plea to the Ministry of Defence for the museum, so he called the present director of the museum and he said that there was no need to worry. I tried to call the museum director as well, but he wouldn’t talk with me.

Olha is now safely in Germany with her children. I continue to search online for news of the museum—it could be shelled, or simply looted—and the lack of news, as I scroll through warnings of air raids and power cuts, impending evacuation corridors, and deaths, seems, in a perverse way, like good news.

The River Psyol below the Anton Chekhov House. Photo by Alison Anderson

The River Psyol below the Anton Chekhov House. Photo by Alison Anderson

On the scale of things, it is only one small summer house with a few precious artefacts donated by the writer’s sister or widow: his medical instruments, a pince-nez, the portrait his brother Nikolay painted of him, a gardening hat worn by his sister Masha. The people of Ukraine are losing, have lost, infinitely, immeasurably more, but the museum remains greater than the sum of its parts, a repository of hope in humankind, a place of pilgrimage for an indestructible faith.

Anton Chekhov’s study and bedroom in the Anton Chekhov Museum. Photo by Alison Anderson

Anton Chekhov’s study and bedroom in the Anton Chekhov Museum. Photo by Alison Anderson

After returning to Moscow in September 1889, Chekhov would not visit Luka again. He wrote to one of the Lintvaryov daughters, “I have left my soul behind in Luka.” The tone of the rest of the letter is jesting, but I like to think these words were written in deadly earnest; a warning to posterity.