In a letter Emily Dickinson wrote to family friend and possible suitor Otis Lord, she posed a question: “dont you know that ‘No’ is the wildest word we consign to Language?” Indeed, Dickinson’s life and art may be read as an experiment in female refusal, one that would reveal something of both its powers and limitations.

Rejecting the roles prescribed to genteel white women of 19th-century New England, the so-called Belle of Amherst did not marry or have children. She shunned polite society, choosing a life of the mind that yielded 1,800 visionary poems. She eschewed fame and, by some accounts, declined to publish. “I had told you I did not print,” she wrote to mentor Thomas Wentworth Higginson. But between 1850 and 1866, ten Dickinson poems ran anonymously in newspapers. Even today, much of her now-canonical oeuvre appears in volumes that omit her trademark dashes and capitalizations, which her early publishers scrubbed in an effort to “regularize” her verse.

So it is unsettling but perhaps unsurprising to learn that a bit of questionably obtained Dickinson memorabilia has been quietly traded among a group of literary men for years: locks alleged to be the poet’s hair (some of which are now for sale on eBay for the astronomical sum of $450,000).

How the poet—who chose to cloister her living body from all but a few visitors—would feel about pieces of it making the rounds is anybody’s guess. The dead cannot give consent. But the alleged Dickinson hair may have arrived on the market by a type of violation: theft. That’s the theory of Mark Gallagher, the English faculty member at UCLA who’s trying to sell the hair on eBay.

“I purchased it on a whim, thinking that, my gosh, someone is going to pay a lot of money for this.”The story goes like this: While an undergraduate at Amherst College in the 1940s, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet James Merrill broke into the home (aka The Evergreens) of Dickinson’s niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Merrill and two friends absconded with personal effects, including a small mirror, “tiny wine glass,” and a manuscript sheet—written by whom, it is unclear. The caper was recounted by Stephen Yenser in a 1995 issue of Poetry magazine dedicated to Merrill, who had died earlier that year. Yenser, Merrill’s literary executor and the now-retired founder of UCLA’s creative writing program, said he heard the tale from Merrill himself. In Poetry, he euphemized what was essentially burglary with terms like “borrowed” and “rescued,” writing that the trio “gained clandestine entry.”

The anecdote has been whispered among Dickinson scholars for years, according to University of Maryland English Prof. Martha Nell Smith, one of the nation’s foremost experts on Dickinson.

“I’ve long been convinced James Merrill did wander off with (steal?) some Dickinson items from the Evergreens, Martha Dickinson Bianchi’s home,” Smith wrote in an email.

Gallagher believes that Merrill must have also taken the hair during the alleged break-in at The Evergreens. Gallagher got his hands on the hair by way of the poet J.D. McClatchy, who, until his death in 2018, shared Merrill’s literary executorship with Yenser. McClatchy’s estate sale, where Gallagher purchased the hair, listed Merrill as the original owner.

Yenser, for his part, denies any nefarious origin for the locks. He says the hair came from an envelope found inside an 1890 edition of Poems by Emily Dickinson that belonged to Merrill, likely purchased from a rare book dealer.

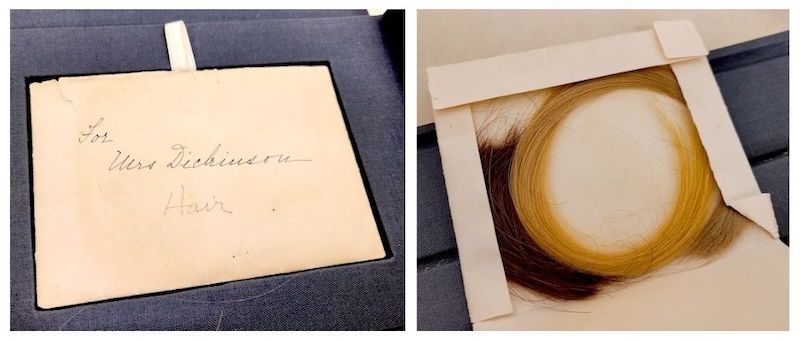

Yet the envelope was labeled in cursive “For Mrs. Dickinson,” and the book in which it was found includes notes from Susan Gilbert Dickinson, according to Yale University, which now holds the volume and provided photos of the artifacts (below). Susan was Martha’s mother, and she and her husband Austin, Emily’s brother, lived at The Evergreens until their respective deaths in 1895 and 1913. Their daughter Martha then moved into the property and “preserved it without change, until her own death in 1943,” according to the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, which controls The Evergreens. As far as Gallagher is concerned it’s quite possible Merrill took the book when he broke into the property.

Photos courtesy Yale University.

Photos courtesy Yale University.

Yenser, however, insists Merrill’s copy was legally procured. Merrill “had other rare books that he seems to have purchase[d], though he was not an ardent collector,” he wrote in an email. “He did not take it from the house.” But there is no documentation confirming Merrill’s purchase of the volume, Yenser said in a phone interview. A representative from the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst wrote that the museum has “no knowledge or documentation of how Merrill might’ve possibly received this item,” referring to the book and the hair found in it. Nor did Nancy Kuhl, poetry curator at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library: “Our records do not include information about Mr. Merrill’s acquisition of the book or its previous owners,” she wrote in an email.

Langdon Hammer, Merrill’s biographer and an editor with Yenser on a book of Merrill’s letters, said he wouldn’t be surprised if the poetry volume and hair had been pilfered from The Evergreens. In an email he wrote that Merrill “and friends like Tom Howkins, who had a reputation for outrageousness, had literary-tinged adventures. Merrill writes about the ‘Proust Party’ they organized in a nearby vacant house. So it seems to me plausible that he broke into the Evergreens to poke around. It also seems plausible to me that one of his friends did so, and he couldn’t resist accepting the loot. I can see why he couldn’t resist claiming the property. And yet not to ever tell this story, to Stephen [Yenser] or Sandy [a nickname for McClatchy] or someone else, is out of character: he too liked a good story, and this one really would be too good not to tell.”

In his biography of Merrill, Hammer writes that during the poet’s time at Amherst he lived in an apartment on Tyler Place, near The Evergreens. “Merrill claimed that he broke in one night with a couple of friends, each making off with an item—he with a sherry glass, in tribute to the color of the poet’s eyes—but it’s unlikely that took place,” Hammer notes parenthetically. In an email, however, he said that he has since learned more and changed his mind about the veracity of Merrill’s story: “I think I dismissed it too quickly.”

Whether the Dickinson locks were among the maybe-looted items remains an unanswered question. But Yenser, it turns out, has some possible Dickinson hair of his own—some of the same locks, in fact, that are now being sold on eBay. His account of how he came into possession of them reads like the opening scene of a public-television drama.

“There’s this kind of magical belief that if we’re close to Emily Dickinson’s hair we’re going to get closer to her, the poet.”One September day after Merrill’s death in 1995, Yenser was combing through Merrill’s Stonington, Conn., library with McClatchy. There in the room—which contained a daybed, desk and a swinging-door bookshelf—an unexpected volume caught their eye: an 1890 copy of Poems by Emily Dickinson, the first published collection of the poet’s work, co-edited by Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd. Upon opening the volume, another curiosity came into view. An envelope. They removed it carefully, lifted the flap and beheld its astonishing contents: two locks of hair, one blond and one “brownish.”

“Our immediate thought was, Jesus, look at it,” Yenser said, recalling their excitement in a phone interview. “This is from Emily Dickinson’s head!”

But who could be sure? The locks could have belonged to other members of the Dickinson family or circle of friends. Yenser and McClatchy suspected the hair couldn’t be tested for a DNA match because it had been snipped in the manner of a haircut, not pulled from the root, which was needed for such an analysis.

Still, the hair was an exhilarating find. While they sold the book of poetry, envelope, and much of the hair to Yale, McClatchy and Yenser kept some strands for themselves, each of them taking one part of the blond and one part of the brownish locks. McClatchy handled the distribution, Yenser said, and mailed the hair to him in a small pouch.

“We would have wanted to keep them, regardless of their physical origin, because they were in the book and because they had some relationship to Emily and her family,” Yenser wrote in an email. He keeps his portion of the locks filed away, he said.

That McClatchy had the hair was no secret: He kept it on display in his home, according to Yenser. Butterscotch Auctioneers & Appraisers of Bedford, NY, described the artifact this way: “two locks of hair purportedly belonging to Emily Dickinson framed together, one of auburn color, the other a brownish-blonde.” They are framed atop a label that proclaims in all caps: “TWO LOCKS OF EMILY DICKINSON’S HAIR.”

McClatchy was convinced that the locks belonged to Emily herself, according to Smith, the Dickinson scholar from University of Maryland. That’s what he told her, anyway, in 1998, when he called to let her know about the Merrill book at Yale, which had been annotated by Susan, she recalled in a phone interview. Smith had been studying the prolific 36-year correspondence between Emily and Susan, which was the subject of her book Open Me Carefully, written with Ellen Louise Hart.

Not only do the letters reveal a passionate relationship between the two women, but they show Susan’s profound influence on Emily’s work. While much has been made of Higginson’s mentorship, Susan was of far greater consequence, Smith argues: Emily made changes according to Susan’s suggestions, while she ignored Higginson’s advice. So Smith was elated to learn of the annotated volume at Yale. She had no interest in the hair that came with it.

“There’s this kind of… magical belief that if we’re close to Emily Dickinson’s hair that we’re going to get closer to her, the poet,” Smith said. “And I think that’s highly problematic. I mean, why? There’s something very gendered about that. Why not spend time with the poems?”

“Our immediate thought was, Jesus, look at it. This is from Emily Dickinson’s head!”Gallagher does, in fact, spend time with Dickinson’s poems. He will teach them as part of his fall course on Major American Writers at UCLA. In an email, he described the class as one that will explore “how female subjectivity and historical constructions of womanhood figure in the works of major American writers, culminating with a unit on Dickinson.” Gallagher does not plan to bring up his eBay listing in class, though he does feel having the locks offers him purchase on Dickinson beyond what the verse itself affords.

“I think I’m just more inspired,” he said in a phone interview. “More so than I would be if I read a poem on an onion-skin page of a Norton critical edition.”

Gallagher recalled monitoring McClatchy’s live-streamed estate sale on his computer from Los Angeles, riveted by the appearance of the Dickinson clippings.

“I see this lock of hair, and I say, oh, this has to go for a little more than a thousand,” he recalled. So Gallagher bid three times, ultimately winning at $800, much to his surprise. “I sold a few Robert Frosts to pay for it,” he said, referring to the rare volumes of Frost’s poetry he said he owned at the time.

An odd fact within this exceedingly odd story is that the “Dickinson hair” Gallagher came to own once belonged to his former professor: While in his doctoral program at UCLA, where Gallagher specialized in the transcendentalists, he took a course with Yenser on Merrill and the poet Elizabeth Bishop. He happened upon the McClatchy estate sale by coincidence, with no input from Yenser, he said. And though he knew Yenser was Merrill’s literary executor, he chose not to ask him about the provenance of the hair. When asked why not, Gallagher declined to comment. Yenser confirmed his relationship with Gallagher and expressed surprise when I told him it was Gallagher who had been the buyer of the hair from the McClatchy estate. But he offered no further comment on Gallagher.

Now Gallagher is trying to flip the hair on eBay. He intends to use the money to pay his student loan debt.

“You know who didn’t have to pay to go to college? James Merrill,” Gallagher quipped, alluding to the poet’s famously wealthy background. In a later email he added that he was also considering donating the hair to his undergraduate alma mater, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

*

In his Poetry tribute, Yenser cited Merrill’s break-in anecdote as evidence of the poet’s roguish personality. As a young man, Merrill was like an acolyte of Hermes, “patron of thieves,” Yenser wrote. “Which patronage, since it presupposes his ability to slip through customs and to invade private property with impunity, is one with the sanctioning of the radical imagination itself.”

Merrill’s “ability,” however, surely had less to do with Hermes than with his elite station: Not only was he a well-educated white male, but he enjoyed extreme class privilege as the son of Charles Merrill, cofounder of the brokerage firm Merrill Lynch. The kind of class privilege that makes it seem ok to break into a woman’s home and take cherished objects—even those that may have belonged to one of the nation’s great poets. At best, Merrill’s alleged raid smacks of frat-boy antics, the kind that reek of patriarchal entitlement and misogyny.

The fetishization of Dickinson’s hair by a group of male poets and academics speaks to the ways in which a patriarchal literary establishment continually reroutes fascination from Dickinson’s artistry to her biography.Whether the locks of hair were among any stolen items is unknown. And perhaps it’s ungenerous to indict Merrill for his purported collegiate heist of Dickinson memorabilia nearly a century ago. Many people do stupid, ill-advised things as undergraduates. The ability to walk away unscathed from such scenarios depends upon a combination of dumb luck and which intersections of identity one must navigate in a nation where justice is unequally distributed. As for Merrill, let it be said: He was a brilliant poet—winner of nearly every major American poetry prize—who died tragically at 68 of complications from AIDS in a nation that shamefully let that disease ravage an entire generation of queer men.

But neither Merrill’s brilliance nor his suffering would make his breach of Martha Dickinson Bianchi’s home, and any theft that followed, less of a violation. Nor do they mitigate the skin-crawling feeling provoked by the supposed hair of the nation’s foundational female poet—whether stolen by Merrill or not—being auctioned off on the internet by a male academic.

Hair is a powerful symbol of racialized gender, and Dickinson’s hair in particular has long been a site of “storytelling, a fantasy about being a (white) woman in the 19th-century,” scholar Sarah Mesle wrote earlier this year in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Yenser himself suggested that the intrigue over Emily’s hair stems, at least in part, from its sensuality. In a phone interview, he called the locks “highly sexed” and “sexually charged.”

For Smith, the fetishization of Dickinson’s hair by a group of male poets and academics speaks to the ways in which a patriarchal literary establishment continually reroutes fascination from Dickinson’s artistry to her biography, the particulars of which have always been framed in sexist terms. Critics have fixated on her choice to live in unmarried seclusion, for example, interpreting it as virginal spinsterhood. In a September 1967 letter to his student Judith Moffett, Merrill himself called Dickinson “the New England old maid par excellence.”

But another way of understanding Dickinson’s lifestyle is through the lens of a woman-centered radical queerness. That perspective has gained some traction recently—as in the 2018 film Wild Nights with Emily, which drew on Smith’s scholarship, and the Apple TV series Dickinson. But for years it had been suppressed in favor of the “old maid” narrative in which Dickinson was lucky to have the epistolary attention of a man of letters, Higginson.

“Are people most threatened by the Emily-Susan relationship because of its sexuality, because of its eros?” Smith said. “It could be that, but I also think it’s very threatening for people to think that this premier poet… that her mentor was a woman who lived next door who was unpublished.”

Perhaps it’s ungenerous to indict Merrill for his purported collegiate heist of Dickinson memorabilia nearly a century ago. Many people do stupid, ill-advised things as undergraduates.Gallagher said he appreciates Smith’s critique. But he is merely one salesman in the vast rialto of literary souvenirs. As an example, he pointed to Sotheby’s recent sale of a trove of objects belonging to Sylvia Plath, which were put up for auction by the poet’s family. Plath’s deck of tarot cards sold for a whopping $200,000, which Gallagher said left him “optimistic” about a big payout for the hair he is pedaling on eBay.

“What do you propose people do with these artifacts?” Gallagher said. “Destroy them?”

*

The only bona fide lock of Dickinson’s hair, which has been described as red or auburn, is kept at Amherst College. The college received the clipping as a gift in 1983 from descendants of Emily Fowler Ford, a friend of Dickinson, who sent it along with a touching note by the poet herself:

I said when the Barber came, I would save you a little ringlet, and fulfilling my promise, I send you one today. I shall never give you anything again that will be half so full of sunshine as this wee lock of hair, but I wish no hue more sombre might ever fall to you.

In 19th-century America, locks of hair were commonly circulated as signs of intimate attachment. Hair cuttings were kept in lockets worn around the neck, incorporated into rings and earrings and were even woven into elaborate bouquets and wreaths. Nineteenth-century poet and journalist Charles Mackay called these objects “spoils rescued from the devouring grave, which to the affectionate are beyond all price.”

Spoils indeed. Gallagher’s asking price for the hair has jumped from $250,000 to nearly half a million over the last month. Whether anyone will pay that remains to be seen. So far Gallagher reports only one serious inquiry, supposedly from a famous buyer whose name he does not wish to publicize. As many as 30 “watchers” of the Dickinson-hair sale have been listed on eBay this month.

Whether the hair Gallagher has truly belongs to Dickinson is perhaps beside the point, as scholars suggest relics draw their power less from a verifiable connection to a body than from the strength of feeling they inspire. Still, one challenge Gallagher may face in his retail endeavor is authenticating the provenance of the Dickinson locks.

“I don’t know any institution that would pay such a ridiculous price for something of questionable authenticity and minimal research value,” said Mike Kelly, Amherst’s head of archives and special collections, which, along with the verified Dickinson ringlet, holds a cache of the poet’s manuscripts, letters and other items. “The research value of a lock of hair is minimal … the last time we purchased a small Dickinson manuscript fragment, we paid only $10,000 for it.”

Gallagher wants to inspect Amherst’s lock of Dickinson hair under a microscope in order to compare it with his and build authenticity. While Amherst does “not generally allow any patrons to handle Dickinson’s hair,” Kelly wrote in an email, “if [Gallagher] were to draft a formal proposal to have a proper forensic analysis done, we would be willing to review and consider it. No formal proposal was ever received.”

The cost of a forensic analysis has been prohibitive, according to Gallagher. “If I find a buyer I will be able to justify paying someone to do the microscopic analysis,” he said.

He thinks the testing will show that his locks “match those at Amherst College,” Gallagher wrote. He described the color of the hair as being redder in person than it looks in the eBay photo.

Even if the test were to confirm a match between the two hair samples, Amherst would only accept the hair as a gift and has “absolutely no interest in bidding for it at auction,” Kelly wrote.

While it is doubtful the mystery surrounding Merrill’s acquisition of the Dickinson locks will be resolved any time soon, Kelly hopes that any evidence of the hair’s theft would spur Gallagher to give it to the Emily Dickinson Museum, which oversees The Evergreens as well as the Homestead, the house where Emily lived until her death in 1886.

“While the statute of limitations has surely expired, there is a clear moral obligation to return this stolen item to its rightful owner rather than attempting to profit from it,” Kelly wrote. “That may be why the auction is happening on eBay instead of through an auction house like Sotheby’s. If the provenance that proves the item’s authenticity is that it was stolen, that’s not something a reputable house would want to handle.”

Gallagher interprets Amherst’s disinterest as driven by jealousy rather than any ethical stance.

“Amherst thinks they own Emily Dickinson,” Gallagher said in a phone interview. “They’re very proud that they have this lock of hair of their own. They’ve been telling everybody that it’s the only one.”

While he considered selling the hair through a traditional auction house, Gallagher said, he decided to go with eBay because that is where he already sells the rare books he collects. He believes the locks of hair belong “in a place where the generations of Emily’s admirers can go and see” them, he said. But he has not been keen to simply give them away.

“I purchased it on a whim, thinking that, my gosh, someone is going to pay a lot of money for this.”