On May 26, Viet Thanh Nguyen and Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood sat down to discuss Rosewood’s new novel Constellations of Eve. The book’s release also inaugurates a new publishing partnership between the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network and Texas Tech University Press. In addition to talking about the new novel, their places in the Vietnamese diaspora, and the writing life, Nguyen and Rosewood also discuss their experiences in the publishing world and how the new partnership hopes to foreground new voices in Asian-American literature. You can read more about the DVAN/TTUP partnership here.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

*

Viet Thanh Nguyen: You came as an immigrant, not a refugee, to the United States at age 12. Can you tell us what that experience was like?

Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood: It was an interesting experience. I came from Vietnam to Singapore and then to Texas. Perhaps it was a shock, but thankfully, being a teenager, you’re kind of used to shock. So I think my transition to the United States was a welcome one.

VTN: A welcome one—why is that?

ANR: That’s a difficult question. Truly, it was personal. I had been separated from my mother for several years before that, and going to the United States was sort of the only possibility that could reunite us. So it was a safe haven in that sense. And I haven’t lived with her for I think about five years prior to landing in Texas. It was like having a family again, essentially.

VTN: Unfortunately, stories of separation are simply way too common in the Vietnamese diaspora. I came when I was four years old, so I basically grew up as an American. But coming at 12, I think you must have carried with you a lot of memories of Vietnam and what life was like there. I’m wondering, how do you relate to these different kinds of identities, labels, and categories that are here in the United States—racial, ethnic, or otherwise?

ANR: Recently I’ve been thinking of myself as having three identities. One is a Vietnamese one. One is a Vietnamese American one. And one is an American one. And I think that I balance all three of these identities, and there are so many nuances between them. How do I often think about exhibiting identity, for example? And to what extent am I performing myself? To what extent am I performing my Vietnamese identity or my American one?

VTN: So give me an example of performing your Vietnamese identity.

How do I often think about exhibiting identity, for example? And to what extent am I performing myself? To what extent am I performing my Vietnamese identity or my American one?ANR: When I’m in the US I have to keep up a certain part of myself to not completely lose touch with my lineage. For example, it’s more important for me here to have a statue of Buddha and have a place to pray to my father. Whereas if I were in Vietnam, I don’t think I would be so deliberate with those actions. I would have a temple to go to. But in the United States, I surround myself with objects, and so objects become a replacement for identities.

VTN: What about the American identity? When do you perform that?

ANR: I’ve thought a lot about what does it mean to be an Eastern and a Western writer. I am trained in the US as a writer, but I have my influences also from the East. Even though Vietnamese people are very outspoken, I think Vietnamese literature is actually very quiet and very subtle. Everything is a micro-expression. A text, a novel is an act of micro-expressions that you have to decipher. Whereas in American contemporary literature, I think there’s more outward passion and rage. And I love both of those things. So I am in between the quiet rage and the expressive, loud one.

VTN: I think of myself as a Vietnamese American writer, Asian American writer, American writer, or just writer. But I know that you have said that you are a Vietnamese writer and an American writer. I would never call myself a Vietnamese writer because I can’t write in Vietnamese. So I’m interested in that. What does that mean for you to say that you are a Vietnamese writer if you’re writing in English?

ANR: I think it’s such a part of my DNA and my voice as a writer. When I say that I’m a Vietnamese writer, it’s that my inspiration and my sensibility are rooted in my upbringing. I cannot write in Vietnamese, but I do hope that I could one day. I know Jhumpa Lahiri just recently came out with her first Italian novel, which she wrote entirely in Italian after having lived there for about a decade. That’s what I hope that I will be able to do as well, but in Vietnamese. I look forward to simplifying language because when you’re learning to express yourself in a language, it boils down to the essence.

When I say that I’m a Vietnamese writer, it’s that my inspiration and my sensibility are rooted in my upbringing. I cannot write in Vietnamese, but I do hope that I could one day.VTN: Most of Vietnamese American literature until recently has been shaped by war and by the refugee experience, which is not what characterizes Constellations of Eve. And we’ll get to that novel specifically. But do you see yourself as a part of Vietnamese American literature? You can say no!

ANR: I absolutely do. And strongly. I think that I am a part of a new wave of Vietnamese American literature that isn’t necessarily about the war. I feel especially grateful to you and Isabelle and DVAN [Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network] for this initiative because it is the kind of gift that keeps on giving. Like you, when you were awarded the Pulitzer, it didn’t just end there. It put out so many other branches. And so for that, I’m really grateful. And I think Vietnamese American literature has many, many branches. I’m happy to be one of those tiny shoots.

VTN: I want to make sure we talk about Constellations of Eve, this new novel, which I enjoyed reading so much. First of all, I want to ask you to tell us in your own words what Constellations of Eve is about.

ANR: Constellations of Eve follows these three main characters throughout three different incarnations of their life, and in each iteration they have a chance to try again. With each reality, there’s echoes of former ones.

VTN: It’s partly built on repetitions and variations. Without giving too much away, it makes a very dramatic opening and then sends us into alternate parallel histories of these main characters. And for me, it brought up this idea that there are so many ways our lives could have branched in different directions based on choices we made or choices that other people made. As a refugee, I often think about what would have happened if the US had made this decision or my parents had made that decision and I had stayed in Vietnam and so on. And your novel explores that territory, obviously, in a very different vein. I know that Buddhist beliefs play some role in your novel, this idea of these different possibilities and realities that our lives could take.

ANR: Yeah. I think the Buddhist belief in reincarnation is a very compassionate one because it allows us to believe that we that we have a second chance and a third chance and a fourth chance, because it seems to me that life is so fickle. People miss each other all the time. And despite our best effort to communicate and despite how much we do love each other and yet we don’t quite manage to love each other in the right way. So I think that’s why I am drawn to that.

The characters are free of ethnic markers. Everything I write is going to have a Vietnamese backbone, but I don’t feel like I need to prescribe it to the characters or to signal it in any way.VTN: The novel does not have anything to do, as far as I can tell, with Vietnam or Vietnamese people. Is that correct?

ANR: The characters are free of ethnic markers. Everything I write is going to have a Vietnamese backbone, but I don’t feel like I need to prescribe it to the characters or to signal it in any way. When I’m in Vietnam, the characters are not described as Vietnamese. I just know they are. So in that sense, it’s still a Vietnamese book, but it’s not signaled as such.

VTN: I think that’s a really interesting response. It raises a lot of provocative issues around what the possibilities are for writers who are marked in different ways. Obviously, in Vietnam, when we’re reading Vietnamese literature, characters are not going around saying, “hey, I’m Vietnamese” or, “hey, this is a Vietnamese cultural custom” in the same ways that white writers in this country are not saying the same things about whatever they’re doing.

ANR: When I published my first book, I deliberately left my middle name Nguyen as an initial, because I didn’t want them to exoticize me or signal in any way. But with DVAN and TTUP [Texas Tech University Press], I know I’m in a safe space and I know that I have people who advocate for me. I am not suspicious about the intention.

VTN: What was the inspiration for coming up with this story?

ANR: I started writing this book around a time when my relationship with my husband, who was then my fiancé, was at a crossroad. And I think this book was a labor of love in many ways, because it was my way of trying to figure out our relationship. How did we miss each other? How did we not communicate? How did we begin to take each other for granted?

VTN: And it’s your second novel. Was it easier than the first one?

ANR: I don’t think any writing is easy. I think it’s weightlifting, and probably I would rather lift weights. It was very difficult for me to write. And I wrote many, many drafts before the one you read.

VTN: Writing is always difficult. With the second or the third book, you would think, if you keep on lifting weights, it should get easier because you get stronger. But the problem is the hurdles get higher because I think we try to do more. I mean, it just basically sucks to be a writer. And if you can’t do anything else, then you know you’re a writer.

One way that your novel is different than a lot of Vietnamese literature is that there’s a lot of sex in Constellations of Eve. In Vietnamese American literature, you get a lot of trauma, typically around the refugee experience, war, combat, death, violence. Not so much sex, and if sex appears, it’s something traumatic. I’m curious about why you made that choice as a writer.

When I published my first book, I deliberately left my middle name Nguyen as an initial, because I didn’t want them to exoticize me or signal in any way.ANR: This book came to me very sensually. Those scenes are, for lack of a better word, a pleasure to write. I was interested in sex after motherhood, after pregnancy. And so there’s a scene that’s not necessarily sex, but of Liam and Eve exploring that after her body is in a different state of trauma. So there’s pain there interwoven. Those are kind of the phases that I’m interested in as a writer, where it teeters between beauty and ugliness, when beauty is pushed to the point where it falls over into something horrendous. Sex can be that for me.

VTN: Death is also a disturbing theme in this novel. Was it hard for you to write on this very dark theme?

ANR: My mom always repeated to me growing up that you came to life the same time that your father passed away. It was so interwoven. This was my mythology, that life and death were the opposite of the same coin. I think there were instances where I felt guilt for being born, because I tied with my father’s death. And, you know, of course, that’s not the case.

VTN: As a Catholic, I agree. Our whole Catholic mythology is built on death and resurrection and terrible violence and sacrifice and rebirth. So I think that’s all in there as well. You know, you mentioned something interesting to me, which is that with your previous novel and your first publisher, you had decided to not use your Vietnamese name in your authorial name because of your fears of being exoticized. It encapsulates the dilemma that so many Asian American writers have. I’ve known plenty of writers who struggled with the same issue. Should they use only their non-Asian names or should they use the Asian names that they had somewhere in the past?

Both answers are situated in this fraught terrain of what Americans consider to be race and the different ways that people have come here to the United States. Did you experience that with the first novel, when you decided against using your Vietnamese name? Did you encounter some of your fears of exoticism?

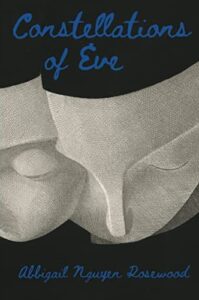

ANR: My first novel had the face of an Asian woman on it. I wrote a really long email to my publisher about that. And they have precedents for using faces, so I’m not blaming them for making that decision. But for me, it was still uncomfortable because I felt like it was just signaling my race for no particular reason. Even before getting a book accepted, I knew that I didn’t want that treatment. I knew that I didn’t want to be pigeonholed. I tried to convey that as best as I could. And everyone at DVAN and TTUP understood it so quickly. As you can see with the cover, it’s about the story and not about me.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I empathize deeply, and I’m glad that we have not gone down that road. So potential authors, we will not exoticize you!

________________________________

Constellations of Eve by Abbigail Nguyen Rosewood is available from Texas Tech University Press