I insisted on the dark city.

I persisted in the dark city.

–Sheila Maldonado

*

Everything I want to say about New York City happened one afternoon in J. Hood Wright Park at the start of the lockdown. Not since the children were toddlers had we spent so much time in this park, five blocks south of our building in Washington Heights. We needed public spaces during quarantine. We needed trees, fresh air, and the opportunity to gather, even at a distance. Without the respite, we’d have gone mad in the cells of our three-room apartment, my family and I, the bewildering spring of 2020 when the boys turned seven and nine.

The governor and the mayor were in some cockfight about what to name the lockdown, and who was running the show. The mayor warned us to shelter in place. The governor thought New Yorkers would riot under such oppressive language. Instead, we were “on pause.” So long as we behaved, the parks would remain open. But to me, pandemic time felt fast-forwarded, not paused, even as the days without childcare were long, because the city and our access to it transformed so quickly. No more trips to the public library or the museum of Natural History. No more subway rides. The routine was pulled out from under us. When you are forty-three in New York City, raising children, you have already lost the New York that mattered to you at age twenty-three. The loss I am talking about is something else entirely.

Somewhere at the beginning of the curve my college roommate called from the West coast to ask if we’d be leaving the city. Where on earth did she think we would go? To my mother’s house in New Jersey, she suggested, or to my brother’s house down South? I told her, edgily, that we were staying put. We would tough it out, I said, as if New York personally gave a fuck whether my family abandoned it. The truth was, nobody had offered us shelter. Maybe they feared we’d infect them. If that were the case, they were right to be afraid. This was a number’s game. In New York City, there were 28,000 of us per square mile, living cheek by jowl. Had we thought about renting a place in the country for a time, my roommate asked, genuinely concerned—somewhere less congested, at least until the curve flattened? “With what money?” I bristled.

Here’s the thing. Before this virus reared its head, we’d sunk all our savings into a down payment on a run down house in the Bronx, at the end of the 1 line. The plan was to get away from the George Washington Bridge and the nexus of highways whose traffic fumes had given my kids asthma along with a third of the other kids in our zip code. In the midst of this global pandemic, we were somehow going to close on this house, fix it up and move in. Our jobs were here, uptown, where we were raising our boys, though now, overnight, we were working remotely from the apartment we’d outgrown in which we were also now teaching home school. We were committed to New York, like married people with children are committed to each other; we were stuck, without free time or space to admit to regret.

“I just think it will be hard, psychologically, to be in the city during this crisis,” my college roommate predicted. “So many people are about to die.” I resented her in that moment because I knew she was right, and because we didn’t have the option to leave.

One night in mid-March the super alerted us to shut the windows. He’d heard some story that turned out to be bullshit about helicopters spraying the city with disinfectant. By April half our building had emptied out. Roughly speaking, the white half. As in the rest of the city, income was the strongest predictor of flight. Some of these neighbors handed us their keys before they fled for second homes or vacation towns, asking us to please shove their packages and mail inside their apartment doors. We said we’d see them on the other side, acknowledging the sudden divide between us. The other side was not the cure, since nobody could say with certainty when the vaccine would start, and this purgatory would end. The other side was anywhere but here in the midst of the outbreak, and when we said we’d see them there, we didn’t really mean it because we didn’t really buy that they were every coming back.

On the surrounding streets of Washington Heights, the immigrant economy vanished overnight.CUNY, my employer, was defunded. A quarter of my colleagues were laid off. Several of them died. Our union begged the governor to tax the rich to save the school for the sake of the common good. I was warned to prepare for furlough. I feared my students’ welfare. There was talk of turning City College’s campus into a bivouac for the hospital’s overflow of patients. “Is New York over?” asked my friend Ayana from across the street. She wore a hand-sewn face mask in an African print called “money flies.” “No,” I told her. “It’s too big to fail.”

Nevertheless, packages started getting stolen from the lobby. The methadone clinic was closed, the local heroin addicts had nowhere to go, the subway trains were rumored to have become mobile homeless shelters. The line at the food bank snaked around the corner. The caceralazo grew more frenzied each night at 7 pm, like we were rattling the bars of our cages as well as cheering for the essential workers—the nurses, janitors, supers, food deliverers, mail carriers and bus drivers who had no choice but to risk their lives to give us life. A lady madly banged a stop sign with the handle of her mop, and on the night she didn’t show to add that sound to the clanging of empty pots, I assumed the virus got her. The rhythm was off. Subway service was suspended from 1 to 5 am.The crematoriums ran around the clock. The supply chain was down. I lost sleep and hair but counted myself lucky to be able to feed my kids.

“This is hard,” wailed my friend Drema from her front stoop in Harlem after her father died of Covid-19. It took her weeks to find a free funeral home to retrieve his body from the morgue because the death business was swamped. She’d been a child in the 1970s and claimed this New York felt like that one—the Rotten Apple. Muggings were up. She felt unsafe now letting her preteen daughter walk alone around the block.

I hid plastic candy-filled eggs in the alleyway near the trash cans on Easter. The newly unemployed lady in 65 baked us cornbread and hung it, still warm, on our doorknob. The old woman in 61 was taken out on a stretcher, feverish, and put on dialysis. The old woman in 33 returned from three weeks in the ER wheeling an oxygen tank hooked up to her nose. The super checked in on her everyday and later got sick with the virus himself. By Mother’s Day I was desperate to escape. I tried, along with the rest of New York City, to foster a dog. I thought a dog would reduce our stress, but all the shelter dogs were taken. It was true. Only the biting pit bulls and hopeless medical cases remained. At some point in May I ransacked empty apartment 34 for children’s books after we exhausted our supply. In apartment 61, they’d forgotten to turn off the alarm clock before leaving, and I heard it beeping for three months through the wall, even in my dreams.

My children changed with the abrupt closure of their school. They lost their baby teeth, their tempers, their social lives, their Spanish. The older one, I feared, was growing less cute—not to us of course, but to others in authority who might, under the wrong circumstances, find him menacing. The changes within the parks were equally abrupt. To prevent social gathering, the playgrounds were locked, the basketball hoops removed, the dog runs closed, the benches roped off with caution tape, police cruising to unevenly enforce the new order.

On the surrounding streets of Washington Heights, the immigrant economy vanished overnight. The sidewalk tables of tube socks, knockoff watches, winter hats and fruit suddenly gone, and in their place on the empty sidewalks—discarded blue surgical gloves and piles of dog shit. The mom and pop shops shuttered, maybe for good, the signs in the windows of the bodegas required face coverings, the traffic on the George Washington Bridge thinned out, the air turned impossibly clear.

Down in the subway, without the usual volume of human trash to forage, the rats were said to be eating each other. I hazarded the A train, to bring our taxes to our accountant’s midtown office, and found the near-empty train car to be a time capsule. Its advertisements from the beforetime made no sense in the new reality. An orchid show at the botanical garden? A “degree with a purpose” from Apex Tech? As the death toll mounted, the soundscape changed—sirens, constant ambulance sirens, underscored by birdsong. As food insecurity increased, the kids’ basketball coach, who had time on his hands with the league shut down, shifted gears to delivering bags of food to hungry families in the hood. Around the corner, down the block, next door, folks were unable to make rent and doubling up, two families in one-bedrooms, ten, fifteen people, Domingo said. They were growing desperate. He predicted that by June they’d be driven by hunger to riot out in the street. The woman from empty apartment 5 texted from Connecticut to say she was bored. Somewhere near peak weak when they were forklifting the dead into refrigerated trucks and digging mass graves in the Bronx, a doctor at the nearby hospital killed herself, unable to take the strain. Meanwhile, the flowers were blooming in the J. Hood Wright, where we dutifully taught the boys to ride their bikes.

*

On the day I want to tell you about, the weeping cherry tree was beginning to bud over by the boulders. Through its veil of pink blossoms were visible the towers of the hospital where they’d already run out of beds. Ahmaud Arbery had not yet been shot on his jog. Breonna Taylor had not yet been shot in her bed. George Floyd had not yet been suffocated on the street. We did not yet have the data indicating the virus was disproportionately taking Black and brown lives from the same zip codes plagued by environmental injustice. We had not yet schooled the boys in these inequities nor closed on the house. All those things were on the near horizon. On this gorgeous spring day, the park was full of people trying to stretch out, find solace, breathe, or play, and my boys and I were among them.

The nine-year-old had sent us on a scavenger hunt. Find a bottle cap. A leaf. A rock. A cigarette butt. A flower. I led the seven-year-old toward the cherry tree to pick a bloom. A well-dressed white woman stood beneath its canopy, serenely photographing its branches with the camera of her phone. I thought I understood what she meant to capture: this cherry tree in the time of corona, this unlikely thing of beauty in the midst of the battered city under the shadow of death. As we drew closer, a soccer ball rolled near her feet, nearly kissing her ankle. It belonged to a Dominican kid, brown-skinned, like my own. In a flash, the woman’s affect changed from peaceful to revolted. “Get away from me!” she screamed at the boy, though it was the ball that approached her, not his body. The boy stopped in his tracks. My boy flinched, too, at the sudden violence in the air. Was he confused by her tone or was he already old enough to get it, and all that lay beneath? The boy’s mother, who was heavily pregnant, rose from a nearby park bench like an avenging angel.

“Don’t you talk to my son like that,” she yelled. “He’s a child. He’s just playing.”

“He’s too close to me,” the white woman claimed. “He’s supposed to be six feet away.” Her voice was full of panic and blame.

“So move your own damn body six feet. This ain’t your house! This the park. He’s allowed to play.”

Above her mask, the white woman looked displeased to have been addressed so rudely, and more than a little afraid, but reluctant to back down. “You’re teaching him to be disrespectful just like you,” she spat.

“Get the fuck outta here or I’ma run you out,” said the mother. She meant it, too. The white woman had the good sense to leave.

The neighbors who had the means to flee have not yet returned.Surely that white woman felt vulnerable to infection. The pandemic was making people jumpy. But it was also magnifying the deep-seated racial and class tensions already in place, tensions over real estate exploitation, gentrification, who owns the city, who belongs to what neighborhood, who gets pushed out of neighborhoods, what it means to be a good neighbor, who has a right to move freely in public space, and whose freedom of movement is policed. When the white woman retreated without apology or consideration for these factors, I bet she thought, “These people are animals.”

Witnessing the fight with my boy, I absolutely took the mother’s side. I felt her righteous anger for all the countless times in their young lives my own kids have already been criminalized, in some cases by their own teachers. There was a lesson for me, in the boldness of her advocacy. Normally, I’m much more polite. But if that white woman, who had no comprehension of her own base knee-jerk disrespect, had not had the good sense to leave the park when she did, I would have joined the campaign to oust her. Quite simply, she did not deserve the cherry tree because she did not understand how to share.

*

There are those for whom New York was only ever a playground, and I feel similarly about them. They never deserved it. Goodbye to all them. It is June, 2020 as I write this. In New York City, 21,000 people have died. The spring has given way to a summer of struggle. Just as Domingo predicted, there are rebellions in the streets, here in New York and all over the world. Home school is now on the art and history of protest. We are in it, marching with the boys. In the middle of Frederick Douglass Boulevard, we paused in a crowd a thousand strong to kneel with our fists raised, and then got up to walk the distance. Until the next wave, we are done with sheltering in place. The sirens are less frequent now. The city is in phase one of reopening, on the cusp of phase two. A lot of the storefronts in our hood are still boarded up. It’s unclear how the schools will reopen come fall. The ice cream trucks have returned. The tables are back up on the streets, only now the vendors are hawking masks. A guy sells illegal fireworks from the trunk of his car. Every night you can hear them popping off. 311 calls are up. The neighbors who had the means to flee have not yet returned. For richer or poorer, better or worse, in sickness and in health, for the love of this hobbled unbeatable city at the epicenter of pandemonium, we stayed. Soon, we will move into the house.

__________________________________

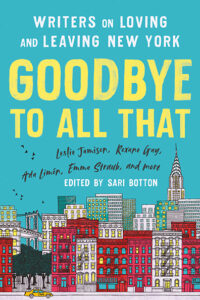

Adapted from Goodbye to All That, edited by Sari Botton. Copyright © 2021. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.