Last period of the day. Charles had decided that morning that he would talk about tessellations. Last period, they should have been covering sines and cosines. They should have been starting to graph but he just didn’t have it in him. Tessellations were his favorite.

When Charles first met Laurel, he’d told her that. He’d told her how much he loved the idea. “Everything has its place,” he’d said, “And when it’s in its place, it makes beauty.” Laurel said laughingly back, “That’s too easy.” She didn’t like easy. She never had. She liked complication. She said, “If it’s not hard, it’s not worth it,” and he had believed her. It had excited him, it still excited him, that willingness to battle. But he knew the danger of those words now. “If it’s not hard, it’s not worth it.” It wasn’t true.

A whole class on tessellations: the subject didn’t deserve a full lesson, but that morning, crumpled on his bony couch, drinking the spit of grounds and lukewarm water that drooled from his second hand coffee maker, he’d bookmarked the graphs in his notebook, stared at the lecture notes he’d penciled for himself in his straight boxy hand, and what was left of his heart had gone out of him. He knew he couldn’t bear it. For once, he wanted to speak with love. He wanted to talk in public about something he loved. And since he couldn’t speak of Laurel and he couldn’t speak of his girls, tessellations would have to do.

It was odd, this desire. It was, of course, he knew, like the ache at the back of his throat and the licks of burn in the pit of his belly and the dryness of his eyeballs, and his relentless insomnia—all of it a good doctor, hell, just an especially empathetic ninth grader, would diagnose it as symptoms of the divorce. He didn’t like to call what was happening by that name. Charles called it “a separation” for his kids and he called it nothing for the people at work when they asked how he was doing. But to himself and to Laurel, he called it by its true name: the cleaving. He always said it as a sad joke, though. “Should we talk about the cleaving?” But Laurel wasn’t having it. “Just call it what it is,” she’d say, sad and a little annoyed, and he would answer, still laughing, that that was what he was doing. That was it’s true name.

She didn’t want the divorce and neither did he, not really, not deep down. But she’d left him no choice. She’d shown herself to be the worst of what anyone could think of her, not just in front of him, they could have recovered, maybe, if he’d been the only one to see her shame. But in front of everyone. It was just as his brother, Lyle, had said, when Charles told him Laurel’s plans to move the family away from Boston, out to the Berkshires, new, better paying teaching jobs for both of them. “Out there with all those white people? It’s what that woman always wanted. It’s going to ruin you, Charles.”

And it had, it had slowly killed them until one night, after the girls were asleep, the two of them had sat in silence in the living room. They’d sat and she kept her head bent low. She’d never bent her head like that before. He’d studied the bend of Laurel’s head and one of the kids had come in, and they’d both turned to her and when they turned back to each other, it seemed, that had decided it.

Charles said, “I don’t think I can live here anymore.”

And Laurel had kept her head down so that he couldn’t see her cry. She spared him that, in the end, she was kind about that. Her voice was low and strangled, “What do you want to do?”

And now, months later, he knew the answer to that question. He wanted to talk to a crowd about something that he loved. It was a pressing need. He felt it keener than the systematic breakdown of his very body without Laurel. He found, in the months since they split, that he was now embarrassingly earnest. He’d been good at being honest about his feelings before. He wasn’t like his brother Lyle, who once told him he only said “I love you” to his wife Ginny on Christmas, and even then, only every other year. No, Charles always prided himself on his effusiveness with the girls. Speaking his feelings was not the problem. It was that when he did it now, it came out deadly serious. He had always prided himself on his humor. This was a list of what he was: a good husband, a good father, a good teacher and a funny guy. But lately, he was sick of jokes. He was sick of joviality. He only wanted to talk about things that he loved.

In the teachers’ lounge, he frightened people. A simple, “See the game last night?” set him off. He would discourse on the beauty of a spiral throw, on the intensity of a team’s surge. Once he even rhapsodized on the splendor of the Celtics’ colors. He knew, even as he was speaking, that his ardor was horrifying. He saw it on the faces of his listeners, how some would widen their eyes and some would narrow and all would eventually turn away, hoping this would get him to stop talking. It didn’t. He talked even more. He wanted, he desperately needed, to speak about all the things he loved, to remind himself they still existed in the world, that the things he loved were multitudes, that not everything he loved was locked away from him in what was now just his wife’s apartment.

The first bell rang and he watched the shadows of the trees on the back wall again. He supposed, if he had to talk about something he loved, he could talk about that. How much he loved the green and how much the green was like Laurel.

He loved that. He loved the green. He loved the country: he always had. He’d grown up in an overstuffed double-decker house on Chalk Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on a block that his parents had come to as children from Barbados. Everyone on Chalk Street was from back home. On Chalk Street, the houses drowsed into each other and the people inside them kept a careful watch out the windows—everyone was lovingly guarding their lives there. Family was his mother and father and older brother Lyle and hundreds of cousins, always asking for favors. You went to Boston and to places where white people were for work, not for life. Life moved from the Chalk Street front porch to Mayflower Meat Market to the bus stop on Mass Ave and back again. Anything outside this circuit was not to be considered real.

But Charles always yearned for wide open spaces. When he was six he’d announced he wanted to be a farmer. His parents were appalled. They hadn’t left Barbados only to have their son turn around and work his way back down into the dirt. No one understood it; his older brother and their friends laughed about it for years.

He hadn’t really known that black people in America could live outside a city, could grow in wilderness, until he found Laurel. When they first met she still smelled like fresh pine sap. It was subtle, most noticeable right behind her ears and under her chin. He’d told her and she’d been mortified and then insisted he must be joking. But he wasn’t. She had always smelled like open country to him. He made her tell him everything about her home: the tree farm, the hills. Once, she mentioned picking fiddleheads from the weeds in the woods behind her house, brushing off their paper veils and biting the fresh curls till they burst into green in her mouth, and she did not find that wondrous at all, thought him odd for thinking so. “It was just stuff you eat as a kid on your way to school, like chewing on hay,” she said, as if chewing hay was normal, too.

The farm was gone by the time they met. Her parents mortgaged it to send her to college and then her father died of pneumonia shortly before her graduation, followed by her mother a few months later. In the wilds of their early love, Charles promised Laurel he would buy it back for her, and she’d said, “Don’t bother.” She told him about the oblivion of Maine, the cotton balls in her ears, the breath suspended. But that didn’t put him off. It made him want it more. Even the racism up there in the country seemed bucolic to him. Much better than the squawks and loud calls of the college students in Central Square who liked to make mark their territory by catcalling insults at him from the doorways of bars he’d walked past for years. He considered it the major failure of his and Laurel’s life together: that at the end of their first decade of marriage, he still hadn’t made enough money to get them to the green.

Laurel knew that, of course. She’d used it to her advantage, when she’d started the long, slow haggle of convincing him to move. She mentioned the money, and the teaching gig at the high school already lined up for him if he wanted it, but they both knew the real selling point was the woods and the trees and the streams. The selling point was the green. The rest of it, those awful stories about the place, didn’t matter.

Charles stood up and went to the board. He erased all the equations he’d written the day before. He’d forgotten yesterday afternoon because he’d been rushing to walk out the same time as his daughter, Charlotte. It was a stubborn desire. She was doing her best to pretend she didn’t know him, a fact Charles found funny and sad. “We’re the only two black people in this place with the last name Freeman,” he’d told her, gently, “They know you belong to me.” Charlotte was tricky. Maybe she would laugh at that, maybe she would be mortally offended. He’d caught her on a day when she was mortally offended—she’d rolled her eyes at him in a panic of embarrassment.

He began writing on the board. The secret of teaching was to set up an ever more elaborate series of scenes. They liked it. They loved it when they found you still writing on the board. It was like getting a glimpse of an actor in a dressing room, putting on his make up before the show. It gave the whole endeavor a frisson of excitement.

As the first of his students walked in, he drew a pale yellow honeycomb on the dull, ashy blackboard. The simplest tessellation. Last period was his favorite because, he was ashamed to admit it, his most devoted students were here. He never understood this waxing adoration. Back in Boston, some years, none of them liked him, many years they outright despised him. But then, sometimes, he would get a group of students like these, who laughed at his jokes, who stayed after class, who seemed to love him. At Courtland County High, it was four boys in the last period on Tuesday, who breathlessly christened him their favorite teacher at the beginning of the year. They were all freshman and all players on the school soccer team, and they seemed to have adopted him, his jokes, and his class as their own personal mascot. There was Nick and Adam and Seth: all awkward bones and muddy knees. Sometimes he caught a smell off of them, the smell of the terrible loneliness of male adolescence, and it made him want to cry. It smelled like tears. He’d smelled the exact same thing on the boys he taught back in Boston, that same strangled melancholy.

The fourth boy in his fan club was Hakim. Hakim was one of the three black boys in the whole freshman class, bussed in, like his comrades, from Spring City. Charles asked Charlotte about Hakim at the start of the year, but she’d bristled at his name, turned up her nose. “He’s alright, I guess,” she’d huffed. From that reaction, he‘d gathered that Hakim, despite his athletic abilities, wasn’t popular, but as he watched Hakim over the next few months, he realized he guessed wrong. Hakim was very popular, one of the most popular freshman boys, always in the middle of a press of kids. The three other boys deferred to him, sometimes waiting for him to laugh before reacting to a joke. But if Charles ever happened to pass Hakim in the hall, the smell of loneliness came off him so strong, it made his eyes water. Sometimes, when everyone else was supposed to be busy with some quiz, he would catch Hakim watching him shyly, quickly glancing away when he realized he was caught. He never paid the boy the indignity of acknowledging this. He suspected that Hakim had led the charge in popularizing his class and he was grateful for that. But he respectfully kept his distance from him, which, he knew, made Hakim’s heart swell for him more and which, in turn, made him love Hakim.

There were five girls, too, who always sat in the front row. Megan, Kristen, Jen A., Jen C. and Doreen Harmon. Poor Doreen, saddled with the name of a different time. She didn’t even have the excuse of the girls Charles had come up with, who could say their parents were from the Islands, didn’t know any better. Doreen’s parents were just lost in time. Or so he imagined.

The greatest impression the girls made on him was “hearty.” Even their acne was well-scrubbed. Down to a girl, the skin on their cheeks was a wind-chapped red and they all wore their hair in scraggly, greasy ponytails, pulled back so tight he could see the knobs of their temples. They wore oversized fleece pullovers zipped up to right beneath their chins, the grubbier the better. They allowed a scrum of dog hair and dust bunnies to nap up their sleeves. This was maybe one of the biggest differences in the students here, besides the obvious one of his old classes being all black and these ones being nearly all white. The girls he taught back in Boston, even the bookworms, would have writhed in mortification if ever caught wearing one of those fleeces. The girls in Boston, it had saddened him to see, wore tighter and tighter clothes each year, growing more swollen, constricting themselves even further in brightly dyed tight denim and greening gold chains. Thank god Charlotte escaped all of that. He hated this town now but he was still grateful it let her escape all of that. Charlotte’s closest friend here, as far as he could tell, was the other black girl in her class, Adia. He found her obnoxious: he had her first period on Wednesdays and Fridays and she made a point of sitting right up front and passionately doodling in a notebook, making a show of being oblivious to the entire class. But he noted with relief Adia’s combat boots and heavy denim skirts and oversized concert t-shirts. No danger of too tight jeans and all they brought with them from that one.

He turned from the board to see that everyone had assumed their places. The girls in the front, his boy fan club a few rows behind them, their fellow students sprinkled in between. In the very back were the louts. This never changed. It didn’t matter if you were in Courtland County or Dorchester, Massachusetts, it didn’t matter if it was 1991 or 1971: the back of the class was for the lost and showily rebellious. It would be that way until the end of time.

“We’re gonna do something a bit different today,” he began. “Today we’re going to talk about beauty, truth, and light. I’m not talking about a laser show or whatever you kids are into—“

The class chuckled. This was a trick of teaching patter: establish an inside joke and make call-backs to it. In his first few days at Courtland County he’d asked, “Y’all do what around here? Fish in ponds? Make mud pies?” and one of them gulped, “We go to the laser show at the community college astronomy lab.” And he’d laughed. The kids thought he was mocking the innocence of it, calling it lame, so they laughed heartily, too. But he’d been generally delighted by the answer, by its decency. Now he joked about it whenever possible, it always got them on his side.

“Tessellations are the most beautiful patterns you’ll ever see, they have the most truth you’ll ever encounter” he began, “And you can find their perfect representation in nature.”

As he spoke, he made his way around to the front of his desk and, with a purposeful squat, hopped on the top, swinging his legs back and forth. He could fall apart and cry and call it a cleaving to Laurel, he could feel his throat ache with tears even now, as he lectured, but he couldn’t show it. Of course he couldn’t show it, he knew, though a part of him wondered why, would forever wonder why. A part of him was always twelve years old. This fascinated him: did everyone contain a multitudes of selves? When he’d raised the question with Laurel, playfully, one night as they lay before sleep, she’d gotten indignant. “Of course everyone does,” she’d sputtered. But the way she’d said it, it was obvious she hadn’t thought of it before, was only defending this answer because she couldn’t bear to think of anyone as different from herself. That was, perhaps, the source of their cleaving in a nutshell. Laurel could not conceive of anyone that she loved not being of the same mind as her. That is what she’d said when he’d raged at her about it all: the alienation and the silence and the humiliation. “I never asked because I thought you would agree, Charles. I thought we were of the same mind.” Himself, he knew he could love those of a different mind but even he had his limits.

“Can someone give me an example of a tessellation in nature?” Charles asked.

“A honeycomb,” Jen A. answered.

“A pineapple. I mean, like, the skin on a pineapple,” Jen C. added.

“Good,” he said, “those are good examples.”

It started from the back of the class. He didn’t realize what it was at first. It honestly sounded like somebody retching and he was momentarily panicked: the one thing that dazed him in a classroom was when a kid was sick. He couldn’t even stand it when his own kids threw up: he would leave the room and leave it to Laurel. His palms began to sweat at the thought of having to deal with it, all while trying not to retch himself. But that wasn’t it. He glanced at the girls in his front row and saw that the Jens wouldn’t look at him, instead were slowly blushing. Megan and Kristen were the same. It was only outdated Doreen who could look him in the eyes, and when she did he realized, with a start, that she was crying.

The boys, his fans, looked murderous. Hakim was staring straight ahead in a mounting, unvoiced rage, his fists clenched and vibrating on his desktop. This was what made him listen closer to the sound. It was wordless and bass and hollow. At first he thought maybe it was supposed to be an owl call, and that was weird, why would one of the louts disrupt a lecture with an owl call?

Charles cocked his head and made a theatrical show of listening again. He thought this would stop it, would put the girls in front at ease, but it didn’t. The sound grew louder.

It was hooting, he realized. It was supposed to be hooting and then it struck him: it was a really bad imitation of a monkey. He sat back against his desk. He folded his arms across his chest, still trying to control the class, while inside he only wanted to cry.

The hooting grew louder.

It was baffling, how even rebellion came in only one shape: slouched shoulders, head low, insult the obvious. In Boston it had been to call him a nerd, to make fun of his smarts, but this was so far from an insult it made Charles love those students more.

The hooting grew louder and louder and Charles leaned back against the desk, his heart racing, love on his tongue, feigning detachment. He told himself I am not angry, I am not angry, I am not angry. He would put it aside. It was what he always did. One of the worst things to do was to lose your temper, was to let them see your anger. It was true of children. He didn’t like to make sweeping generalizations but he had learned it was true of white people, too. Anger had to be carefully deployed. Children and white people, they expected you to become angry, they thrilled at it, a little bit. They pretended to be afraid, but it was a game some of them liked to play with black men. His students back in Boston had done the same: he had never wanted to give them the satisfaction of getting angry.

He took in deep, slow breaths. He tried to think of what would be the best next move.

Someone screeched “eee-iiii-oooo” and this gave him something to work with. He turned and smiled brightly and said, concise and clear, “Let’s get one thing straight. A bunch of little boys are not capable of embarrassing me. I’m still the one who decides whether you pass or fail. No amount of noise changes that.”

There was more rustling. One of the kids in the back leaned forward: a long skinny tibia of a freshman named Martin Wade. He’d never had a problem with Martin before. In fact, Martin had always struck him less as defiant and more as terminally bashful. But now Martin leaned forward, one oversized Adam’s apple bobbing with self-loathing and fear, and he shouted loudly, “Ooga booga, ooga booga” to the laughs of his friends.

And Charles turned around and called back without thinking, “You know, you’re awfully lucky you boys are white.”

He didn’t know why he said it. It had broken out of him. He’d wanted to speak with love: that was all that he’d asked for that day, but now there was a shocked silence. Martin still leaned forward, his mouth agape. Oh shit, Charles thought. I’m fired for sure.

And then, a miracle. The whole classroom broke into relieved laughter. The girls up front giggled through their tears, his fan boys laughed expectantly. Hakim’s whole face broke into a proud, wide grin, even though his hands stayed clenched in fists. Even Martin Wade grinned. “Oh, you burned,” the boy beside him called out, and swatted Martin’s stringy tricep.

How did they get the joke, Charles wondered, as he smiled thinly at the class. How did they get the joke?

He let the laughter wash over him. It was the first time he’d spoken truthfully in Courtland County, without pretense. It was the first time he’d spoken the truth without trying to make it a joke. He let the laughter wash over him and he watched the light spattering against the back wall of his classroom, dashing and dappling and turning his classroom walls to mud.

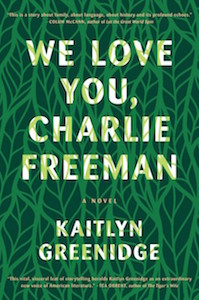

From WE LOVE YOU CHARLIE FREEMAN. Used with permission of Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2016 by Kaitlyn Greenidge.