On a typical afternoon, Joseph Cornell might stop in at his local Bickford’s restaurant for a cup of tea and a slice of cherry pie. One can see him now, a thin, wraithlike man at his own table, bent over a book while enjoying his snack. He reads intently, absorbed in a biography of Chopin or Goethe or some other formidable figure, pausing only to scribble a note on his paper napkin or to gaze with birdlike keenness at a waitress. Cornell was a great reader of biographies. His library included dozens of books on poets, musicians, and scientists, among others, and they attest at least partly to the difficulty he had in sustaining friendships. He fared better with the deceased. He loved to immerse himself in the lives of the illustrious dead, with whom his identification was intense, and who became his most valued coffee-shop companions as they sprang to life inside his bony box of a head.

One suspects it never occurred to Cornell that one day he himself would become the subject of a biography and that someone, somewhere, would perhaps sit down at a table in a coffee shop and open a book about him. The idea would have struck him as ludicrous, for his life was less a story than a strange situation. For most of his years, he resided with his mother and handicapped brother in their small frame house on Utopia Parkway in Queens. Cornell was no bohemian, just a gaunt man in drab clothes whose days were spent mainly in his basement workshop, where he arranged marbles, metal rings, and other frugally poetic objects in small shadow boxes — and transported five-and-dime reality into his own brand of unreality, which to him was as real as the objects in his boxes.

A reticent existence, a series of unrequited crushes on women, numberless days passed in his basement dreaming of long-gone Romantic ballerinas — his was hardly a life in the grand sense. It was different, at any rate, from the lives Cornell read about, and modesty would have led him to protest that his life could not compete for greatness with the historical figures who filled his daydreams. His insomniac nights and long days of frustration were conspicuously short on plot. Day in and day out, it sometimes seemed to him, he did little more than bicker with his mother, feed peanuts to the blue jays in the yard, and listen for the sound of the mailman on the front steps.

His biography, if such an entity were imaginable to him, could have seemed only a grim joke, an assemblage of remarkably unremarkable moments. A biography needs a hero, a Picasso or a Jackson Pollock, someone to get drunk, smash up cars, and bed women. Cornell didn’t drink, never learned to drive, and, to his regret, died a virgin. On the other hand, Cornell was no stranger to desire. For women he felt a deep reverence as well as a nearly breathless longing. In his sixties, he finally relented and had his first physical relationships. But up until then he was unable to permit himself anything as impulsive as a love affair. An art monk, Cornell was determined to repent, for what sin he was not quite sure. Of one thing, however, he was sure: he was drawn to a vision of chasteness for himself, a vision that governed the arc of his life as well as his work. Paradoxically, the same impulse that condemned him to a lacerating aloneness would lead to romantic rapture in his art.

If Cornell didn’t view himself as a major figure, the appraisal offered by his contemporaries was scarcely more generous. During his lifetime, he typically was dismissed as an odd-duck figure lost in the distant and irrelevant past. His shadow boxes, with their intimate scale and nostalgic spirit, seemed to go against what Ezra Pound called the “make it new” spirit of twentieth-century art, an impression reinforced by Cornell’s timid and apprehensive behavior among his many art-world acquaintances.

Today, however, no one could accuse Cornell of artistic inconsequentiality. Though out of step with his own time, Cornell is certainly in step with ours. He was not the first artist to work in assemblage, but he was the first of any note to devote his entire career to that medium, keeping it alive during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. He needs to be acknowledged as a leading forerunner of the junk-into-art aesthetic that has dominated the American art scene since the 1960s, and he can fairly be described as the most undervalued of valued American artists.

Even as an art-world personality, Cornell, in truth, defined his era as fully as did Picasso or Pollock. His life was a genuine New York story. Cornell loved to wander the metropolis, a gray shadow of a man making the rounds of bookshops, record shops, and the city’s handful of avant-garde galleries. From a bench in the airless waiting room of Grand Central Terminal, he wouldwatch the crowds stream by. From his post in Union Square Park, he would observe flocks of pigeons with equal fascination. His urban rambles were made in a New York that no longer exists — a city of fedoras, Automats, and ten-cent cups of coffee, a city where the El still ran along Third Avenue and everyone smoked, a city where phone calls were made from booths. Cornell was the quintessential New Yorker: the loner who couldn’t stand to be alone, and who looked to the city as a place in which to live out his dream of connectedness.

Still, none of this exactly amounts to high adventure, as Cornell would have been the first to concede. If one imagines him bristling at the notion of a biography of him, he would have, in all fairness, grounds for complaint: he was a private man, and no one person ever knew much about him. Although he kept a diary for more than three decades, his journals are a compendium of fragments and seemingly unconnected details whose gaps speak more loudly than anything he wrote. Cornell placed a silence around him like a bell jar.

What, one might reasonably ask, can be gained from disturbing that silence with a biography? Some might say nothing. Nowadays, biography is an unpopular genre, at least among art historians. Formalists contend that an artist’s life is irrelevant to his work and attach to the recording of day-to-day activities a suspicion of triviality. Leftist scholars, schooled in Marxism, are likely to view an individual life as the sum of social, political, and economic factors; artists, they say, are molded by forces far greater than themselves.

True, history creates us, but not as much as we create it. And Cornell, in spite of his own disavowals, certainly helped shape the art of the twentieth century. If a biography needs a hero, in Cornell we have one.

- A Dressing Room for Gilles, 1939; construction, 15 × 8 5/8 × 11/16 in. Cornell never visited the Louvre or saw Watteau’s great painting Gilles, but he used a photostat of it in his work. The sad clown of the painting’s title, whom Watteau depicted at an outdoor fair, is transported in Cornell’s box to a dressing room decorated with harlequin wallpaper.

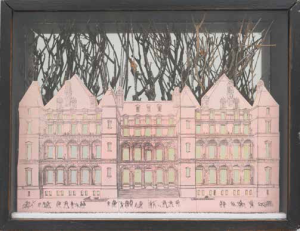

- Rose Castle, 1945; assemblage, 11 1/2 × 14 15/16 × 4 1/16 in. When Cornell made his Rose Castle, he used an old engraving of a Renaissance palace, cut out the windows, and inserted two mirrors behind them. When you peer into the box, you see your face reflected at odd angles, creating a fleeting, quasi-Cubist self-portrait.

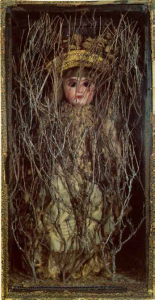

- Untitled (Bébé Marie), early 1940s; construction, 23 1/2 × 12 3/8 × 5 1/4 in. After finding a Victorian doll in a relative’s attic in his native Nyack, New York, Cornell situated her for the ages in a fairy-tale forest contrived from silver-painted twigs.

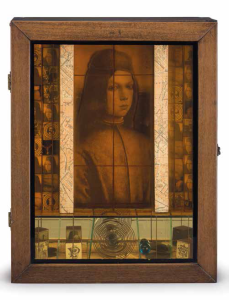

- Medici Slot Machine, 1943; construction with hinged door. This box, which was previously owned by the great collector Edwin Bergman of Chicago, was sold at Christie’s in 2014 for $7.78 million, the highest price ever paid for a work by Cornell.

- Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall), 1946; construction with blue glass, 20 1/2 × 16 × 3 1/2 in. Cornell first became obsessed with Lauren Bacall one rainy Monday afternoon, after stumbling alone into a movie theater in Flushing and seeing her in her film debut, To Have and Have Not.

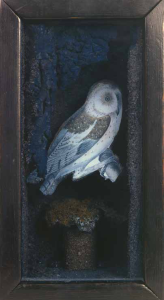

- Untitled (Owl Box), c. 1948; construction, 10 1/8 × 5 1/2 × 3 11/16 in. This captivating blue-hued box was given to the artist Jasper Johns by his art dealer, Leo Castelli, as a birthday gift in 1993.

- Untitled (Aviary with Parrot and Drawers), 1949; construction, 17 1/4 × 14 × 3 1/4 in. The stacked wooden drawers that appear in this box make it a harbinger of the Minimalist movement of the 1960s, which glorified repeating geometric forms.

- Penny Arcade (re-autumnal), 1964; collage, 12 × 9 in. The Penny Arcade series of collages were conceived as a tribute to Joyce Hunter, a waitress in a midtown diner who captured Cornell’s fancy.

From UTOPIA PARKWAY: THE LIFE AND WORK OF JOSEPH CORNELL. Used with permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2015 by Deborah Solomon.