One day, while W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender were students at Oxford, Spender told him that he was thinking of stopping writing poetry. Auden stopped in his tracks, took firm hold of Spender’s arm, and said, “You must keep writing poetry, Stephen—we need you.”

After relocating to America in 1939, Auden lived on Middagh Street in Brooklyn, and in Manhattan on Cornelia Street, East 52nd Street, and then, for a long time, at 77 St. Mark ’s Place and was a parishioner at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, though he made a point of leaving the latter in the 60s when the rector modernized the liturgy and removed the pews.

Frank O’Hara told me that once, around 1949, while he and John Ashbery were at Harvard, they were in the Grolier Bookshop together and saw Auden browsing the shelves. Nothing passed between Auden and the then very young poets. After Auden left the shop, John said to Frank, “Wouldn’t you think he’d know?”

Frank also said that Auden’s poem beginning “It was Easter as I walked in the public gardens” inspired some of his “lunch” poems. Another time, at the Free University on the Lower East Side, Frank spent a whole class reading aloud from Auden’s long work The Orators.

Like many great poets, Auden said provocative but inaccurate things, like “There is no daylight in New York.”

In April, 1939, Auden and William Carlos Williams read together at Cooper Union. Later Williams wrote of Auden: “There is no modern poet so agile—so impressive in the use of the poetic means. He can do anything—except one thing.”

One of Auden’s early books is called The Double Man. In it, he quotes from Montaigne: “We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.”

A masterful, funny, and genuinely pornographic poem of his called “The Platonic Blow” was pirated by Ed Sanders, who printed it in 1965 as a supplement to an issue of Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts.

I met Auden only once, at a dinner party in the late 60s at the journalist and songwriter Irving Drutman’s uptown apartment. I was late for the occasion because of the poetry class I was teaching at the New School for Social Research, and by the time I got there, not only had everyone else sat down to dinner, but Auden had already drunk a lot of wine and was, as he liked to say, “tiddly.” I sat next to him at the table while he held forth, precisely and with great emotion, about his life. “It took me 50 years,” he said, “to know that I belong to the same social class as my parents.” He left right after dinner, which was, Irving Drutman told me, the usual thing (“early to bed”) for him. Later it occurred to me that he had made his remark about family class structures for my benefit.

Auden was born in York, England, on February 21, 1907, within a few years of my parents, not to mention Willem de Kooning, George Balanchine, Edwin Denby, and Count Basie.

He wrote his first poem in 1922, at age 15; it was entitled “California,” and the first stanza reads:

The twinkling lamps stream up the hill

Past the farm and past the mill

Right at the top of the road one sees

A round moon like a Stilton cheese.

He wrote poetry, plays, essays, an oratorio, kept a commonplace book, lectured and taught in various schools and colleges, edited anthologies, and collaborated on opera libretti (including one great original, The Rake’s Progress) with his long-time lover Chester Kallman.

He was a rarity in the 20th century for being both witty and profound.

He said, “A professor is someone who talks in someone else’s sleep.”

He also said, “Real poetry originates in the guts and only flowers in the head. But one is always trying to reverse the process . . .”

As with Keats’s poetry, the first few lines of some of Auden’s most famous poems tend to be better, or any way more memorable, than what follows. One example is, “Lay your sleeping head, my love, / Human on my faithless arm,” and another, “It was Easter as I walked in the public gardens.”

Coming out of the bathroom at a Greenwich Village party in the early 60s, I overheard Richard Howard in the hallway telling how Auden kept “an apple on his desk to remind him of the deliquescence of the world.” (Ugh, I thought, though it was Richard’s haughty way of delivering the word “deliquescence,” as if he owned it, that was maddening.)

“What about Ashbery?” asked an interviewer in the early 70s. Auden (grinning): “I don’t understand a thing he’s written.”

He left strict instructions in his will that no letters of his should ever be published and asked his friends to burn whatever letters from him they had.

He was a heavy smoker, and in his 50s, came to look puffy and creased, the result of Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome, or pachydermoperiostosis, “in which the skin of the forehead, face, scalp, hands, and feet becomes thick and furrowed,” like elephant hide.

He liked wine and pills (uppers and downers).

He died on Saturday, September 29, 1973, sleeping on his left side in bed in a hotel room in Vienna.

“One fine summer night in June 1933,” as he told it,

I was sitting on a lawn after dinner with three colleagues. We liked each other well enough, but we were certainly not intimate friends, nor had any one of us a sexual interest in another. We were talking casually about everyday matters when quite suddenly and unexpectedly, something happened. I felt myself invaded by a power which, though I consented to it, was irresistible and certainly not mine. For the first time in my life I knew exactly—because, thanks to the power, I was doing it—what it means to love one’s neighbor as oneself. I was also certain, though the conversation continued to be perfectly ordinary, that my three colleagues were having the same experience. (In the case of one of them, I was able later to confirm this.) My personal feelings towards them were unchanged—they were still colleagues, not intimate friends—but I felt their existence as themselves to be of infinite value and rejoiced in it.

I recalled with shame the many occasions on which I had been spiteful, snobbish, selfish, but the immediate joy was greater than the shame, for I knew that, so long as I was possessed by this spirit, it would be literally impossible for me deliberately to injure another human being. I also knew that the power would of course be withdrawn sooner or later and that, when it did, my greed and self-regard would return. The experience lasted at its full intensity for about two hours when we said goodnight to each other and went to bed. When I awoke the next morning, it was still present, though weaker, and did not vanish completely for two days or so. The memory of the experience has not prevented me from making use of others, grossly and often, but it has made it much more difficult for me to deceive myself about what I am up to when I do . . .

__________________________________

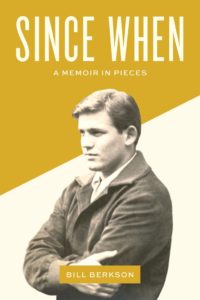

From Since When: A Memoir in Pieces. Courtesy of Coffee House Press. Copyright © 2018 by Bill Berkson.