ALLEGORIC LOT NO. 2:

WINDOW MADE OF LIGHT

Artist: Olafur Sánchez Eliasson

Listing: 5M

The retired seamstress Margo Glantz didn’t wake her son until after dinner. During the preceding week, Margo Glantz, who suffered from insomnia, had been feeling irritated by the presence of her son, David Miklos, who, for his part, suffered from narcolepsy. David Miklos had lost his job at the checkout in the Farmacia del Ahorro because he’d fallen asleep on more than one occasion. For the last week, he’d spent the whole day taking sudden naps in odd corners of the house. Since she wasn’t aware of his condition, Margo Glantz considered him to be an idler, a layabout, and a sluggard. Secretly, she envied his ability to sleep at any hour of the day.

On Monday afternoon, while David Miklos was having another inopportune nap in the armchair, Margo Glantz stuck a row of postage stamps on his forehead, licking each one with the tip of her tongue, and carried him to the post office. She set him down gently on the counter and asked the assistant to send him to Surinam. The girl looked down her nose at her and said that it was impossible to carry out her request as she was four stamps short—Africa needed nine stamps and the parcel only had five.

But Surinam’s in South America, you idiot, she retorted.

Then it’s twelve stamps, corrected the girl.

She also said that the post office was about to close, so she would have to come back the following day.

Margo Glantz returned the next day and the next, with David Miklos sleeping peacefully in her arms. But she always needed something else—a stamp, a notarized letter for oversized packages, more money, official identification, the full zip code for the address she had given in Paramaribo. The girl—who, though not the same one each time, appeared to be so due to the robotic demeanor and characteristic affectation of all post-office girls—would give her a disparaging look and ask her to come back the following day.

On the morning of the seventh day, a Sunday, Margo Glantz decided to let David Miklos sleep on. She woke up early, had a warm bath, and went to the pet shop. As there were no dogs for sale, she made do with a secondhand rabbit. She named it Cockerspaniel. The rabbit was very old, almost venerable, so when she tried to put a lead on it to take it out of the store, it resisted. She carried it home in her arms and set it down on the living room floor, at the foot of the armchair in which David Miklos was still sleeping.

Margo Glantz—slowly, and making as much noise as possible—dragged a chair from the kitchen to the livingroom. She put on a record by the singer Taylor Mac, sat down, crossed her legs, and, singing at the top of her voice, stared at Cockerspaniel, who in turn looked at her with an air of extreme peevishness until he closed his eyes and fell into a deep sleep. She noticed that Cockerspaniel had chosen a sunny patch of floor to sleep in and felt intensely envious. She thought about taking him straight to the post office and sending him to Surinam— or wherever. But she immediately rejected the idea when she remembered that the disgusting, ridiculous, inefficient post office didn’t open on Sundays. Later, she attempted to wake the rabbit, but he just briefly fluttered an eyelid and went back to sleep.

The afternoon went by with Margo Glantz watching her son and Cockerspaniel sleep, noting how the animal’s small, furry body slid almost imperceptibly across the room as the sun sank in the sky and the parallelogram of light entering through the window and falling onto the floor moved toward the wall, indicating, in this way, the passage of the hours.

When the sun had finally set, and the patch of light had completely disappeared, Cockerspaniel opened his eyes. Margo Glantz was standing above him, holding a saucepan by the handle. Using the base of the pan, she hit him five times on the head. Once Cockerspaniel was dead, she carefully skinned the rabbit and cooked it in rosemary, bay leaf, and white wine. After she’d finished her dinner, she tenderly woke her son and opened the living room window wide, letting in the cool, damp night air.

ALLEGORIC LOT NO. 3:

RAT AND MOUSE COSTUMES

Artist: Peter Sánchez Fischli

Listing: 3M

The young lady Valeria Luiselli, a mediocre high school student, stammered and overused the suffix –ly. As her parents, Mrs. Weiss and Mr. Fischli, wanted her to give a speech at her fifteenth birthday party, they sent her to singing, elocution, and public speaking classes. Her party was to be a very elegant celebration in the neighborhood dance hall, and the girl needed to prepare herself for the occasion.

For the elocution and public speaking classes, they hired the famous teacher Guillermo Sheridan. The first sentence that Professor Guillermo Sheridan taught Valeria Luiselli to say was: “Titus Livy had a conk like a coconut and Octavio Paz was a big head.” Despite the shortness and simplicity of the sentence, it took the young girl a lot of effort to pronounce it correctly. Every time she made a mistake, Professor Guillermo Sheridan would hit her on the palm of the hand with a cane. The girl had to repeat the same sentence 112 times before her teacher called an end to the first session.

That night, while they were eating a dinner of octopus a la gallega with white rice, the girl’s parents asked her how her first public speaking class had gone, and if she had learned anything useful that she would like to share with them. The young girl said:

Titus Livy was a cokehead.

What’s that, my girl? asked her father.

Titus Livy was a cokehead, repeated the adolescent.

Valeria Luiselli’s parents looked each other in the eyes and ate the rest of their octopus in silence.

That night, the young girl’s progenitors put on their plush rat and mouse costumes, and, instead of reading or watching television, as they did almost every other night, they committed an act of outlandish, noisy, uninterrupted coitus. When they had finished, still halfdressed in their costumes, the couple lay silently staring at the ceiling.

ALLEGORIC LOT NO. 4:

SHIT MOUNTAIN

Artist: Damián Sánchez Ortega

Listing: 4M

Yuri Herrera, captain of the Alpha Patrol, was voted best traffic policewoman in 2011. One sleepless Sunday night, Captain Yuri Herrera memorized the whole of the famous speech from Macbeth that begins, “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow . . .” She recited it in front of the mirror one last time at 5:25 a.m. while arranging her hair into a bun, held in place by a number of bobby pins and barrettes. Then she put her whistle between her teeth and blew.

She went out into the street looking impeccable. As she was turning the corner of Amapola and Amapolas, she met her fellow policewoman, Vivian Abenshushan, the Omega Patrol’s hostage negotiator.

What’ve we got today, Abenshushan? she asked.

The 10-14 in Avenida Morelos in 11-27 toward Parque del Amor, partner. We’re just in time.

Captain Abenshushan was taller and stronger than Captain Herrera, but they were equally valiant.

At that moment, Terence Gower and Rubén Gallo, owners of the Couscous & Chopsticks public sauna, came by, mounted on identical bicycles, and waved to the two policewomen. The officers straightened their shoulders, smiled, and returned the greeting by blowing their whistles. At that moment, the 10-14 passed, wound down the window of his brown Nissan Tsuru, and threw an empty plastic bottle in their direction. The bottle fell at Captain Abenshushan’s feet, and, furious, she kicked it as hard as she could into the street. Thanks to the friendly cyclists, they had, once again, failed to apprehend the 10-14 who chucked an empty Coke bottle at them every morning. My life is a mountain of shit, said Captain Abenshushan in a slightly theatrical voice. Captain Yuri Herrera, who, being older, was better prepared to resist the blows of another day, identical to the one before and the one to come and the one after that, recited to her partner, in the vehement, earnest tone only learned in the police academy, the Shakespearean monologue she’d memorized the night before.

Captain Abenshushan listened attentively, harboring the vague suspicion that her partner was beginning to go soft in the head. But she immediately repressed this thought deep within her and blew her whistle twice, in a demonstration of gratitude for Captain Herrera’s empathy. Feeling they deserved a break, Captains Herrera and Abenshushan decided to have breakfast at the gorditas stand owned by Toño Ortuño, Las Gorditas de Pancho Villa, on the corner of Isabel la Católica, in the hope that the morning would pass quickly.

ALLEGORIC LOT NO. 5:

PROSTHETIC LEG

Artist: Abraham Cruzvillegas Sánchez

Listing: 6M

One day Unamuno went to the store to buy hens’ eggs. Unamuno didn’t eat eggs, but his wife, who had a wooden leg, wanted to make an omelet and asked Unamuno to go to Daniel Saldaña París’s store and buy eggs. She explicitly requested that they be white, not brown.

Unamuno came back from the store with a paper bag full of brown eggs. Looking into the bag and noting that the eggs were not the color she’d wanted, the woman shouted, Idiot! and made him go back to the store for white eggs.

Unamuno went back to the store, where, this time, he bought white eggs. When he returned home, he found his wife asleep on the bed. The woman had left her wooden leg leaning against the rolltop desk, as she always did when she took a midmorning nap.

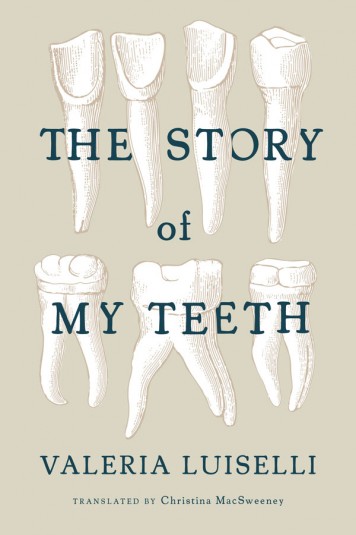

From THE STORY OF MY TEETH. Used with permission of Coffee House Press. Copyright © 2015 by Valeria Luiselli. English translation © 2015 by Christina MacSweeney.