Iveragh

Just after midnight she walks out the door, steps over frost-stiffened grass, and approaches the grey shape of the Vauxhall. She slings her suitcase into the back seat, slams the door, then opens the driver’s side, sits behind the wheel, pulls the door toward her. She turns the key in the ignition, places her palm on the cool, vibrating knob of the gear shift, and allows herself one moment of hesitation. Her white cottage, an unlit rectangle against a sky busy with stars, is as grey as the car. The turf shed is grey as well, squatting at the back of the yard. There is a moon somewhere, but she refuses to look for it. She flicks on the lights. She shifts into reverse.

The grass of her own lane flattens under the wheels; then, when she turns the car, an ill-repaired road with a ribbon of similar grass at its centre appears in her windscreen. Three miles of hedgerows accompany her to the crossroads at Killeen Leacht, with its single tavern, dark and empty, and its wide, slow river. Salmon are gently turning in their sleep under that shining water. Salmon and the long green hands of water weeds, shaken by the current.

Soon she is deep in the Kerry Mountains, disturbing flocks of sheep drowsing near potholes, and birds probably huddled in hidden nests. The car’s lights bounce on the stone bridges of Coomaclarig and Dromalonburt, then illuminate the trunks of last standing oaks of Glencar. She wants the constellation tilting in the rear-view mirror to be Orion, and when it follows her for some time along the hip of the mountain called Knocknacusha, she concludes that it is. Climbing to the Oisin Pass, she thinks about the ancient warrior Niall had spoken of, the one who had searched from that height for lost companions but not found them. He ’d been gone for three hundred years, Niall said, but the woman he was with made him believe it was only three nights. He had lost everything, Niall insisted, for three nights with a woman.

She descends to the plain. Lough Acoose, still and dim under faintly lit clouds, slips into her side window. On the opposite shore the hem of a shadowy mountain touches the water. Ten minutes later there is the town of Killorglin, and then the Laune River, oiled by moonlight.

Goodbye, she thinks, to all that. Goodbye to the four flashing strands of the Iveragh Peninsula, to the bright path of surf in St. Finian’s Bay, the Skellig Islands freighted by history, the shoulders of mountains called Macgillicuddy’s Reeks. Goodbye to her own adopted townland, Cloomcartha, to the kitchens that had welcomed her, and to dogs whose names she had known. Goodbye to her own small drama–that and the futile, single-minded tenaciousness that had almost maintained it. The changing weather patterns, the gestures, the theatrical light.

An hour and a half later she reaches the smoother roads and quieter hills of neighbouring County Limerick. She accelerates, and as she does, she begins to visualize the abandoned peninsula unfurling like a scarf in the wind, gradually unwinding, then letting go, mountains and pastures scattering behind her on the road. “Iveragh,” she says out loud, perhaps for the last time. The landscape, she knows, will forget her. Just as Niall will forget her. What she will forget remains to be seen. She imagines her phone ringing on the table and no one there to answer it. This provides a twinge of pleasure until it occurs to her that it might not ring at all.

She leaves the car in the airport parking lot, knowing it will be towed, stolen, or junked when it becomes apparent that no one is coming back to claim it. The sky, overcast now, is a solid black, echoed by greasy black macadam. It begins to rain in a half-hearted way as she walks with her suitcase toward the lights of the terminal, leaving, she hopes, such full preoccupation and terrible necessity. She is leaving the peninsula. Leaving Niall.

* * * *

Ten hours later, the airliner on which she is travelling shudders, preparing to descend. The window is an oval, the shape of a mirror that once hung on a mother’s bedroom wall. A mother, she thinks, and a mother’s bedroom wall. What she sees through this oval is the blurred circle of the propellers, then a broken coastline, froth at the edges and rocks moving inland as if bulldozed by the force of the sea. Now and then an ebony ocean emerges between long arms of altostratus clouds trailing intermittent rain. Altostratus. One of the words Niall has slipped into her vocabulary, along with geomagnetism, cyclonic, convective, penultimate. Ultimate.

All night the hum of the engines has remained constant, but reaching this shore the sound changes, the Constellation banks, and the seascape below tilts to the left. There are caves and inlets, and the curve of a sudden beach like a new moon near dark water. The noise diminishes and the cliffs move nearer until she can see the ragged cut of the bitten periphery, then the uninterrupted northern forest, moving inland.

She searches in her handbag, finds a cigarette, and lights it while staring at the blue flame near the propeller, which for a moment echoes the reflected orange flame of her lighter. While she smokes, the roar of the aircraft intensifies, then diminishes again, like an argument. One silver wing dips toward the sea, and she sees a freighter half a mile or so beyond the rocks of the coast. She believes the ship is fully lit and of a great size, waves cascading over its long deck, pale castles of ice on the bow in the full dark of a late December afternoon. But it is autumn, not winter, and the day is opening, not closing.

She cannot visualize the cockpit of this very domestic plane, this padded and upholstered airborne parlour called a Constellation. More than fifteen years have passed since the war, the Air Transport Auxiliary, and the intense relationship with aircraft that filled her then-vivid life. The young pilot she had been then, the young woman behind the controls, would have been disdainful of what she has become: a sombre person with the bright centre of her life hidden, her days unfolding in the pause that seems to define this half-point of the twentieth century. Fuselage, she thinks, instrument panel. These terms are still known to her, but she has, beyond her facile drawings of aircraft, no real relationship with them. She has become unknowable, and very likely uninteresting. She has blamed Niall for this, and for much else, though she knows it has been her own acquiescence that has caused her to become, in every possible way, a passenger.

Her younger self would have been disdainful of the clutter of what passes for comfort in this airborne interior: the seats that become beds, the blankets, the linens and tableware. She can remember evenings when, after a day of ferrying warplanes, the moon would sit complacently over the dark airfield and the makeshift bunkhouses where she and her flight companions would sleep. She can recall whispered confidences and bursts of laughter, the sense of guardianship, inclusion. And now, more than a decade and a half later, she is being flown into nothing but personal scarcity. She leans her head against the curved frame of the window, trying to bring the communal engagement of the war years back into her heart. But when she closes her eyes, the memory of a map falls into her mind.

Because it was drawn on a narrow slice of paper, she had believed Niall had placed a drawing of a river in her hand. Then she had looked at it more closely and had seen there was only one shoreline moving down the sheet, defining thumbsized spots of blue. Bays, he had told her, the beginnings of open water in a cold climate. Whoever made it must have been working on the deck of a ship that was following the coast, he had said. It was one of the few gifts he had ever given her, and she cannot now recall the occasion that had prompted it: only that it had moved her, and she had not told him how much. She would never, now, be able to tell him how much.

She opens her eyes, turns back to the oval.

What she sees below is not quite arctic, is a mirror image instead of the sea cliffs that were visible after the takeoff from Shannon, except there are far too many trees now to mistake this country for Ireland. The cliffs appear to be wilder, though the surf breaks around them in the same familiar way. As the plane lowers more purposefully, making its final approach into Gander, Newfoundland, the pine forest approaches. Sea, rock, then acres and acres of forest. Like all transatlantic flights, the aircraft would refuel in this bleak, obscure place. The passengers would disembark for an hour or two.

Tam recalls the bright new American aircraft she had sometimes been instructed to pick up at Prestwick in Scotland: Mosquitos often, or Lancasters. Those planes had set out for the transatlantic part of the journey from the place that is now directly below her, as Ferry Command had been situated at Gander. She had always wanted to pilot a transatlantic flight, but it was understood that no woman would ever be invited to do so, regardless of her skills or accomplishments, so the idea of Gander had remained a vague point of intersection to her, situated between one important shore and another. Soon her boots will be on Gander’s transient ground, however: all these years later. You bide your time in a temporary place like this, she thinks. You make no commitment. This is the geography of Purgatory and the aircraft is about to touch down.

She had always enjoyed “touching down,” noise and power and forward momentum lightly brushing the ground, then settling in, becoming calmer, silencing. She recalls the satisfaction of a completed mission, the pleasure of performance. But now she believes that when she lands it will be as if an idea, something tonal–a full weather pattern, Niall would say–will have closed up behind her, and she will be in the final stages of leaving him.

In the mountains of the Iveragh, he had told her, there would always be times of scarcity. But the old people of the Iveragh knew the difference between scarcity and famine. There is hope in scarcity, the old people had said. She had heard them say it. They had said it to her.

There was no hope in her. Not anymore. From now on she would starve.

* * * *

Niall had been born in a market town on the Iveragh Peninsula of County Kerry–the Kingdome, he called it–and except for university and a handful of years working for the Meteorology Service in Dublin, he had never lived anywhere else. Sometimes he would recite the ancient names of the peninsula’s townlands and mountains when she complained, as she occasionally did, of his silence, until, laughing, she would ask him to stop. Those names were tumbling around in her mind now, mixed with the sounds of the engines. Raheen, Coomavoher, Cloonaughlin, Killeen Leacht, Ballaghbeama, Gloragh. Beautiful places, as she had come to know, though diminished by the previous century’s famine and then by ongoing, unstoppable emigration.

Niall’s direct antecedents had survived the famine. Probably by their wits, he ’d said. They had not perished in the mountains, he told her, but had made a life for themselves instead in the town. Nor had they later run up the slopes of mountains during uprisings or in the tragedy of the civil war, as those in the rural parishes had done. He had shown her the memorial plaques that were scattered here and there around the countryside at the places where rebels had been shot or beaten to death. He had had a sentimental, if not a political, sympathy for those desperate boys and the songs that were sung about them. “‘We ’ll give them a hot reception,’” he had sung to her more than once, “‘on the heathery slopes of Garrane.’”

No one in the family had taken the boats from Tralee either, he ’d told her. There were none of them in London or New York. Not until his younger brother, Kieran, of course. Kieran, who had been the first of the tribe to go.

Goodbye to Niall and his impossible, lost brother. Goodbye to the heathery slopes of Garrane.

* * * *

Niall had himself once made the journey to America, seeking his brother. He had bought a ticket to New York and spent his holidays tramping through the streets of that city, from flophouse to flophouse. After this, he stayed away from her for more than a month, and his phone calls–the few times he made them–were brief and tense. When she did see him, he would not describe his life to her in any kind of detail. It was during periods like that, when he went silent, that she knew he associated her with everything that was dark and wrong. She was a mistake he had made or, worse, a crime he had committed. She was misdirection, shame, something for the confessional, though he never went to confession. At times like that she would begin to suspect that he had taken a vow against her.

So Niall too would have spent some time in this airport. She thinks about this as she descends the lowered steps that lead to the ground. He would have heard the hollow sound of his footsteps on these aluminum stairs, the slap of his shoes on this damp tarmac.

* * * *

Now she is entering a cool room filled with yellow-and-orange leatherette benches, the tiles beneath them polished, light from the large windows mirrored on the floor like long silver pools. Certain details surface in the room, this waiting room: the four clocks announcing the time in distant cities, the acidic green of the plastic plants placed among the banquettes, hallways leading to washrooms and restaurants, and at one of these entrances, a sign with the black silhouettes of a man and a woman, lit from behind.

She walks down the corridor and pushes open the door of the women’s washroom. Inside she finds herself in a pink-tiled antechamber. There is a series of mirrors above a counter in front of which a number of stools are bolted to the floor. She sits on one of the stools and becomes slowly aware of her face in the mirror. By habit she takes lipstick out of her handbag and paints her mouth. She had sometimes felt that beauty was the one, perhaps the only, gift she could give him. She looks for a moment at her wan skin, her own exhausted eyes. Then she reaches for a tissue and angrily removes the colour from her lips.

* * * *

Minutes later she stands at the end of the hall outside the washroom and gazes across the passenger lounge toward a colourful wall, only a part of which is visible from this vantage point. She wonders if what she sees is a large map, but as she walks into the room itself it becomes clear to her that she is looking at an enormous painting: oranges and greens and blues. It holds her attention for several seconds before she turns toward the window where the dark shape of the airliner can be seen, along with the fuel truck that is connected to it by a thick hose. A soft rain is falling now, but there is no hint of wind, no storm. The low light and the rain obscure the fir trees that had been so clearly visible at the end of the runway. The plane is lit from within. The line of yellow oval windows looks faintly yet ominously militaristic in the weak light, much more so, oddly, than any of the warplanes she had flown in the past. She turns away from the window, back to the mural.

There are children of various sizes, placed here and there across the painted surface. Some of them are toylike–not dolls exactly, more wooden and brightly coloured than dolls. They resemble nutcrackers, she decides, remembering the ballet she had been taken to as a child. In spite of their fixed expressions, they seem to be filled with an anxious, almost terrible, anticipation, as if they sense they are about to fall into a sudden departure from childhood. All around them velocity dominates the cluttered air. Missile-shaped birds tear the sky apart, and everything is moving away from the centre. How strangely sad, she thinks, that children should be affected by such abrupt arrivals, such swift departures. And their stance, the way they stare out and away from the frantic activity surrounding them, is resisting this. It is a kind of defiance. She turns back to the room, walks to an orange banquette, and sits down, facing the mural. But she is no longer looking at it because she is once again thinking of Niall.

Her Kerry kitchen had been closer to the earth than the rest of the house: two steps leading down into it from the parlour. She is seeing Niall now, sitting on the first of these steps early in the morning after one of their few full nights together. Behind him the morning sunlight was a path into the parlour. But he was turned toward where she stood, in the darker morning kitchen. How strange they were then, still tentative in their reunion after months apart. She recalls how she had walked over to him and pulled his head toward her hip, her hands in his hair, and how his arms were warm around the backs of her thighs. He was still stunned by sleep and it seemed to her that they had remained in this embrace for a long time. She couldn’t remember disengaging, or when exactly they had broken out of that moment. She couldn’t remember how they had moved through the remainder of the morning.

She glances at the clock, under which the phrase GANDER, CROSSROADS OF THE WORLD is printed in large red letters, then out the window toward the airliner. It is almost eleven a.m. The rain, intermittent upon landing, has settled in, and a dull shadow has darkened the fuselage and dimmed the lights of the plane. “A common greyness silvers every- thing”: that one line comes into her mind, Niall saying it in relation to literature and weather. Shelley, or was it Browning? He had told her that silver was the colour most often, and inaccurately, associated with weather, something about climate theory that, even when he explained it in detail, she had not quite grasped.

The plane is blurred, the runway has vanished.

There is no argument with fog. In its own vague stubbornness, it wields more power than wind, rain, snow, even ice. During the war, just a hint of it cancelled all plans, all manoeuvres. Having no access to radar, she and the other ferry pilots in the Air Transport Auxiliary had flown beneath the clouds, following roads and rivers, sometimes even a seam of limestone, from airfield to airfield. Once she had flown along Hadrian’s great wall in a wounded Hurricane that had coughed as it plowed through the air, a dangerous situation, but one not impossible to manage. Fog was impossible. There was no avoiding it, no manoeuvring around it. The flight here in Gander would be delayed.

All the children in the mural accept this. They do not intercede on behalf of themselves or anyone else. Neither their defiance nor their anxiety has anything to do with the world outside the painted landscape where they live. They themselves would never change, and are uninterested, therefore, in a world undergoing constant revision.

* * * *

Whenever anyone asked her about her childhood, she would always reply with one word: temporary. No one had ever taken the conversation further, until Niall. “Isn’t everyone’s,” he had said, the words meant as a regretful statement of fact rather than a challenge. He did not ask for an explanation, which may be why she had provided one. “I felt trapped in it,” she said to him, “trapped in my body, which wasn’t aging fast enough to please me. I wanted out.”

“Of your body?” He laughed.

“No, I just wanted that to grow. I wanted out of my childhood.”

“I ran with a brilliant pack of boys all over the hill behind the town,” he said. “We ’d only go home if the midges came out, and even then reluctantly, and only after the tenth bite.” He told her he still saw some of these boys–men now–in the Fisherman’s Bar in the evenings. They were labourers, he said. A few had gone to London or New York, work in the parish being so scarce. A distance had developed between him and those who had either returned or remained, something to do with the stability of his own employment, he thought. His brother, Kieran, however, had neither returned nor remained.

There were things, she told him, that had made her childhood more livable. A dog, belonging to a boy she played with and whose house was connected to the walls that surrounded her father’s property, the little village her father essentially owned. She didn’t mention the boy himself, though he had made her happier than she knew. Later it had been the nearby airfield. She had hated it at first, this airfield. The whole village had been destroyed to build it. Compulsory purchase. Expropriation. Miles of Cornish dry-stone walls were bulldozed, she ’d told Niall, ancient fields, and, yes, the whole village. It had felt to her as if some of her childhood had been destroyed at the same time because she had always believed that the good part of it had taken place outside, not inside, her father’s walls. “Since I was a toddler,” she said, “I’m certain I preferred to believe this.”

Niall had particularly liked her descriptions of her early life among a gang of village boys–the men’s club, her mother had called them. As she had grown older and other girls her age began to go to dances and house parties in the company of just one boy, the tomboy in her had remained stubbornly emplaced. She and the boys had on occasion tracked down couples parked in cars, interrupting their intimacies by jumping up and down on the rear bumper, chanting insults, then running away.

“Football with ‘The Boys of Barr na Sráide,’ the Upper Street,” Niall, the athlete, had said. He mentioned that there was a poem, one that had quickly become a song. “Back in the hills where my brother lived,” he added, “almost every story, even a simple anecdote, turned into a song.”

She remembers now that she had never heard the song about the Upper Street, “Barr na Sráide.”

A room full of leaf shadows and the two of them talking, explaining themselves: what had they looked like during their hesitant, first conversations? Very early in the morning, because it was often Saturday, when he had the afternoon free, a diagram of the day’s forecast would have been chalked up by him in the weather station near the town where he lived. He had spoken about this, as if he were embarrassed about the way he spent his days. “I am a meteorologist,” he said, almost shyly, “and in these parts that means I spend most of my time measuring rain.”

She told him about her war. Day after day she would have departed to fly somewhere with only a map and the predictions of the meteorologists to guide her. Likely she would have had an instruction manual in her hand as well, for the Mosquito or Spitfire or any of the other half-dozen aircraft she and the others might have been required to ferry on that particular day. “Forty-seven aircraft, I flew four dozen different kinds of planes during the war.” She added that there had been a number of women pilots, all quite young. On the final run of the day, one or the other of these girls would fly from airfield to airfield picking up the others who had delivered planes to different military locations or to factories. Once, returning to the base, seven or eight of them were seated in the back on the floor of an Avro Anson, knitting.

He had been entranced by this. “Was he any good, then, your weatherman? Had he predicted fine weather for the knitting?” She could feel his body shaking with laughter.

“No,” she said, smiling.

“But you trusted him, I expect, took his advice.”

“No, I did not.”

There was a good chance that the day’s weather had already been telegraphed from the Kerry Station by Niall’s boss, McWilliams, or by his own father, as bad weather arrived in the west of Ireland first. “It bursts in from the Atlantic,” Niall said to her, “like the front line of an army aching for a battle.” He opened his arms expansively. And then there was his laugh.

Aching for a battle, she thinks now.

There had been sun moving on the wall as they spoke, and now and then, when the wind shook the fronds of the sallies on the lane, it travelled across the pillow and into his hair, gold and red, so that when she thrust her hands into it, it was warm.

“Why was it you didn’t trust him?”

It had taken a moment to remember that they had been talking about her war-time meteorologist. “Because our weather person was a woman,” she told him. “And, yes, I trusted her completely.” He laughed again, his face opening with delight, when she told him that the woman’s nickname was Wendy Weather.

She walked outside with him that day into the dampness of the late afternoon. Two fields away toward the mountain, they had seen a heron rise from the marshlands, then fly purposefully in the direction of the lake. “He will have a nest there, Tamara,” Niall said, “or she will.”

She preferred the single syllable of Tam. But the sound of her full name carried by his voice, the formality of that, drew her to him in a way that surprised her.

Sitting now in the airport, looking at the Constellation cloaked in mist, then back toward the sun yellows and night colours of the mural, she thought about his and her own resistance. She had always run away. But after the fact of him, what they were to each other, she had come to an uneasy sort of rest. “I’ve nothing to make you want to stay,” he had said to her, more than once. “Nothing but trouble. You could step into desperate trouble from something like this.” When early on she had asked about his children, he explained that it hadn’t been possible or, at least, that it had never happened. “Sometimes,” he said, “it is as if he was my child and I somehow lost him.” When she asked, he was astonished that she hadn’t known he had been speaking about his younger brother.

* * * *

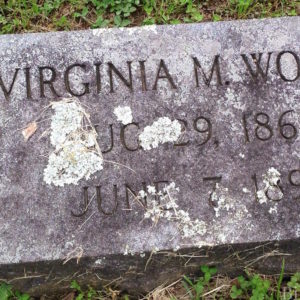

The house where Niall’s brother had been raised still stood near the heathery slopes of Garrane, looking as if it had grown out of the rough pasture. Beside it, one of the Iveragh’s disordered burial grounds tumbled down the hill toward the bog below. The brother had lived there in his later childhood, and into young manhood under the care of the country woman that Niall would refer to as Kieran’s Other Mother, and was happy there, Niall had said, in a way he had never been in his own home. Niall had shown her a newspaper clipping concerning his brother, and two black-and-white photos, one with the brother astride a bicycle, grinning. Kieran was a chancer, Niall said. You never knew what he was going to do.

“Dead?” she asked gently, having noted his use of the past tense.

“I hope not,” he said, not looking at her. “I don’t think so. In England or maybe America, for a long time now. He just vanished in the night. Working, or so they say, on building sites or perhaps the motorways.”

Later he would begin to look for his brother in the most desperate of ways. It was my fault, he said. My fault.

It is even darker outside the window now, as if the fog is trying to cancel the struggling light.

From THE NIGHT STAGES. Used with permission of Picador. Copyright © 2016 by Jane Urquhart.