Terrence didn’t pull into the Lees’ driveway. He idled the car along their quiet street.

“Well,” I told him, “I’ll probably be right back.”

It was early evening, and still light out. The air was warm and still. We knew Alice Lee probably would be home after her day at the law office. I walked up a few wooden steps and knocked on a white wooden door. Its old brass knocker had “Alice F. Lee” engraved in feminine script. I took a step back. Nothing.

I pressed the doorbell, stepped back again, and waited. Nothing. All right then. At least I tried. I’d wait another minute, then join Terrence in the air-conditioned car and call it a day.

Just before I turned around to go back to the car, a tiny woman using a walker came to the door. She had large glasses and wore a tailored light blue skirt and matching suit jacket. Her gray hair, parted on the side, was clipped neatly in place with a single bobby pin. I introduced myself. She leaned in to hear better. I raised my voice and repeated who I was and why I was there.

“Yes, Miss Mills. I received the materials you sent. And the letter.”

Her voice was a raspy croak. She had read what I sent about Chicago’s library system picking To Kill a Mockingbird for One Book, One Chicago. From her sources, she knew I had been making the rounds. I had read about Alice Lee, Harper Lee’s much older sister. She was eighty-nine years old and still a practicing attorney. From the clips I’d seen, I knew she often ran interference for her sister, politely but firmly declining interviews. I was surprised when she invited me in.

Across the threshold, a musty smell greeted me. A large oak bookcase, shoulder-high and to my right, dominated the small entryway. Just beyond a short hallway was a small telephone nook. A little white chair was pulled up to a waist-high ledge with the telephone.

“Please come in,” she said.

I followed Alice Lee into the living room. Books were everywhere. They filled one bookshelf after another, stood in piles by her reading chair, and were stacked on the coffee table and most available surfaces, for that matter.

She saw me taking all this in. “This is mostly a place to warehouse books.” She smiled and her eyes crinkled at the corners. I strained to catch what she was saying. It wasn’t just the raspy voice that made that difficult. I was still learning to decipher the local accent, more pronounced in the older people I met. Of course, around here, I was the one with the accent. “When I hear a consonant,” Harper Lee once said, “I look around.”

“Pull up that chair, won’t you?” With her hands still resting on her walker, she nodded at a low wooden rocker by the piano on the far wall. The living room was compact. I carried the chair four or five feet and set it near hers. She stood by a gray upholstered recliner and a side table piled with papers.

I was thrilled to be invited in, but I felt a rush of regret, too, for bothering her, especially now that I saw for myself how petite and vulnerable and, well, ancient, she appeared to be, with so little hearing and the gray metal walker. “For balance,” she told me.

The interior of the house was as modest as the exterior. An old plaid couch with skinny wooden arms was pushed against one wall. A floor lamp and another side table piled with books and papers were between the couch and the recliner. Along the far wall was an old brown piano. Above it hung a painting of the sea that was more angular, more modern, than the rest of the living room. Another wall had a fireplace flanked by two upholstered chairs. Glass and porcelain knickknacks formed a silent sentry atop the white, wooden mantel.

She slowly lowered herself into the chair, then let go and dropped the last few inches. She managed a dignified plop into her seat. As we spoke, I heard someone rustling around in the back. The kitchen was just off the square dining room, which, in turn, was just around the corner from where I sat with Miss Alice. No room was very far from another.

Some of the bookshelves in the dining room were waist high, others a bit lower. Pushed against any wall that had room for them, they had the haphazard zigzag of a city skyline. But the window above one of them looked out on a deep, dark backyard with towering trees.

Alice answered my questions about the book, the town, their family, her famous sister. I scribbled in my reporter’s notebook, putting a star by quotations I thought I might include in my story.

Big homes or expensive clothing didn’t interest her sister, Alice told me. “Those things have no meaning for Nelle Harper,” Alice Lee said. “All she needs is a good bed, a bathroom, and a typewriter. . . . Books are the things she cares about.”

Her sister teased Alice about the time she began storing books and newspapers in the oven. She didn’t cook and had run out of bookshelf space.

A pleasant aroma was coming from the back of the house. I couldn’t place it. It was the scent of baking bread, only fainter.

Could that be Harper Lee in the kitchen? The possibility was electrifying. Was she listening to our conversation? Would she make an appearance? I thought it better not to ask.

Meantime, I could feel a sheen of sweat on my face. No air-conditioning on here. Alice easily got cold but not hot, she told me. She had grown up without air-conditioning and rarely felt the need for it.

“I hope it’s not too warm for you,” she said. Her voice was almost a croak.

“No, not at all. Thank you.”

I waited until she glanced away to quickly swipe my hand across my forehead and wipe it on my pants.

I had stepped into another era without AC, computers, or cell phones. The Lees had only recently purchased a television. A manual typewriter rested on a chair in the dining room. Nelle used it to answer some of the correspondence that still poured into their post office box. “She doesn’t even have an electric typewriter,” Alice said. “We do not belong in the twenty-first century as far as electrical things are concerned.” She paused. “Hardly even the twentieth.”

I mentioned that in To Kill a Mockingbird, the word scuppernongs had sent me to the dictionary.

She got a gleam in her eye. “Follow me.”

She led me to the kitchen. It looked unchanged from the fifties.

The floor was black-and-white-checked tile. The cabinets were painted white. Stacks of papers, bowls, and cracker boxes and various piles of just stuff crowded the counters.

My unspoken question about who was doing the cooking there was answered. A tall black woman with wisps of graying hair stood at the stove. She poked at the frying pan with a spatula. She was making fried green tomatoes.

Alice made the introductions. When her sister—Nelle Harper—was in New York, Alice explained, Julia Munnerlyn was her live-in help. She looked after Alice, stayed overnight, drove her to and from work, and fixed the simple meals Alice preferred. And her favorite food, fried green tomatoes.

I would come to learn that one of Julia’s sons, Rudolph Munnerlyn, was Monroeville’s police chief, the first African American to hold that position.

“She wanted to know about scuppernongs,” Alice told her. Julia slipped the breaded green tomatoes out of the pan and onto a plate with a paper towel to absorb the grease. She worked with the deft hand of someone who has done that a hundred times before. She had kind eyes, watchful eyes, and a warm smile for the stranger in the kitchen. She reached into the small, white refrigerator and retrieved a big bowl.

Julia put the bowl on the counter to my left and set out a paper towel.

“For the seeds.”

She and Alice beamed at me. “Try one,” Alice said.

Both women were amused that this local fruit was exotic to me. “A friend brought these by the other day,” Alice said.

The scuppernongs did indeed look like big grapes. They were reddish purple, plump, and sweet with just a bit of tartness as well. As I slipped the seeds into the paper towel, I was trying to take it all in: the scuppernongs; the two women; the considerably cluttered, somehow comfortably dated interior of this house. Chances were I’d never see it again.

They told me that scuppernongs grow on vines, and were plentiful around here. Both were in good humor. The affection between the two women was obvious.

Poor Terrence was still out in the rental car. But I knew he knew the longer I stayed, the better.

“Would you care for a little tour of the house?”

“Well, sure. Thank you.”

Julia dipped a second batch of slices in breading and, with a practiced hand, slid them into the frying pan.

Despite the walker, Alice was light on her feet. She stepped carefully but quickly. Her walk across the fairly narrow kitchen was almost a skitter.

I realized I was still holding the crumpled paper towel. “Is there a . . .”

“I’ll take that,” Julia said. She threw away the paper towel and returned to the stove.

Julia soon finished making the fried green tomatoes and covered the plate with a paper towel.

I nodded at Julia. “Very nice to meet you.”

She gave me a warm smile, still looking amused. “Nice to meet you, too.”

I followed Alice into the rather dark hallway, with wooden floors, on the other side of the kitchen. It led to the home’s three bedrooms. First, immediately on the left, was a small bathroom with pink tiles. A pair of women’s stockings hung to dry. Above the sink, a dental appointment reminder was tucked into the side of the mirror.

Across the hallway was a compact room with a spare bed. This was the only bedroom with a window on West Avenue and the blinds were drawn. The room held additional bookshelves and, on a small table, the fax machine that was Alice’s lifeline to friends and family now that her severely limited hearing made phone calls impossible. It was Alice’s quickest link to her sister in New York and even her friends just down the street.

Every week, she told me, Nelle faxed her the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle. The puzzles were a shared pleasure, one they had in common with their mother.

Alice began to tell me about their family. Frances Lee had died in 1951. Nelle was only twenty-five then and still adjusting to life in New York City. She worked as an airline reservations clerk and wrote on the side. To Kill a Mockingbird wouldn’t be published for another nine years. Only six weeks after Frances Lee died unexpectedly that summer, following a surprise diagnosis of advanced cancer, Alice, Nelle, and their middle sister, Louise, lost their only brother, Ed. He was found lifeless in his bunk one morning at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery. Only thirty years old, he’d had a brain aneurysm and left a wife and two small children.

The sorrow of those events still flickered across Alice’s face as she recounted them a half century later. When she spoke of the shock of the two deaths, Alice dropped her gaze, and her already raspy voice grew scratchier.

“Daddy was a trouper,” she said. “He lost his wife and his son in a short period but he kept going.” And so did Alice. At work at their firm, the two of them took refuge in the purpose and routine of their shared law practice.

The following year, Alice and A.C. moved to this house from the family’s longtime home on Alabama Avenue where Frances Lee gave birth to Nelle in an upstairs bedroom, where Nelle and Ed climbed the chinaberry tree in the yard, where A.C. pored over the Mobile Register and Montgomery Advertiser every day and indulged his fascination with the crimes detailed in magazines such as True Detective.

But Alabama Avenue was growing more commercial, and the tranquility of West Avenue appealed to father and daughter. A.C. had suggested the move to West Avenue before the events of that terrible summer, but Frances wasn’t interested. She didn’t want to leave the street where she had friends for a wooded area being newly developed. She’d been out there, to visit a friend who had just had a baby. The memory prompted an affectionate chuckle from Alice. “She said she didn’t want to move out there with all the owls and bats.”

On her extended visits home from New York, Nelle had a new place to call home. As a girl, she liked to watch her father in action at the courthouse. As a woman, she still accompanied him to the law office some days to work on her manuscript about the character he inspired, Atticus Finch.

Alice and her house held a wealth of Lee family stories. In this spare room with the fax, we lingered in front of a bookcase. I asked Alice about their favorite authors. High on her sister’s list, she told me, were William Faulkner and Eudora Welty, Jane Austen and Thomas Macaulay. The first three are familiar names to most people who’ve taken high school English, whether or not they remember what they read. Nowadays, Home Alone actor Macaulay Culkin has far greater name recognition than Thomas Babington Macaulay, the British writer, historian, and Whig politician. Thomas Macaulay died in 1859. More than a century later, Culkin’s parents named him in honor of the original Macaulay. Fame is a strange beast.

Alice preferred nonfiction, especially British and American histories, and Nelle devoured those, too. I spotted a shelf lined with many such histories. Judging by the jackets, some were recent, but many were published decades ago.

“Have you spent time in England?” I asked.

She ran her deeply lined hand across the spines of a row of books. It was a tender gesture. Loving, even. “This,” she said, “is how I’ve traveled.”

Alice’s room, down the hallway a bit and on the left, had a bed with a bright pink coverlet, an old dresser, and, naturally, a crammed bookcase. Other books were in piles on a chair and on the floor. Still more books and rafts of papers were scattered across half the bed.

Like her father, I would later learn, Alice had a peculiar reading habit at bedtime. She would lie flat on her back and hold the open book above her face to read it. Seems like an uncomfortable position but it worked for A. C. Lee and it worked for his daughter. If Alice couldn’t fall asleep, she had her own version of counting sheep. She silently ran through the names of Alabama’s counties. Or American vice presidents. Chronologically. But in reverse order.

At the end of the hallway, she showed me Nelle’s bedroom. This originally was their father’s quarters. It was as modest as the rest of the house. When Nelle was in New York, Julia occupied the room. The walls were blue. Built-in bookshelves lined the wall to the left of the door. A small figurine of a cat perched on a shelf at eye level. A trunk sat under one window. A small door led to the private bath.

As fascinated as I was by this unexpected house tour, I didn’t want to overstay my welcome. But Alice brushed aside my concern about that and continued the conversation.

My thoughts turned to Terrence again. I told Alice that he was out in the car. Would it be okay if he came in to take her photograph?

“Well, yes. All right. Invite him in.”

I hurried out through the darkness to the rental car. It was still a warm night but not nearly as warm and close as in the house.

Terrence lowered his window. He grinned.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry.” I said it so fast it came out as one word. “I had no idea I’d be in there so long. That is Miss Alice. She’s wonderful, Terrence. Come on in. She said it’s okay to bring your camera.”

“Oh, fantastic.” Terrence followed me up the wooden steps to the front door.

Already I was looking forward to telling him about my conversations on our drive back to the Best Western.

“I hope you have enjoyed your visit to Monroeville,” Alice told Terrence.

“Very much.”

We chatted some more in the living room, and then Terrence, tentatively, got down to business. “Is this good here?” he asked. Alice had resumed her spot in the recliner.

“Yes.” Alice smiled at Terrence but also looked a touch wistful. “I never did like photographs of myself. The problem is they look like me.”

Terrence spoke to her gently, put her at ease as much as he could. “I just hope I don’t crack your camera,” Alice told him. She said this with the wry delivery I came to know well. The real life “Atticus in a Skirt,” as Nelle called her, had that in common with the novel’s quiet attorney. Just as a neighbor in the novel observes of Atticus, Alice could be “right dry.”

Alice had one request for me. Could I stay on long enough to interview the Methodist minister who was a good friend to both Lees? I said I’d like to and I’d ask my editors if I could extend my visit.

I inquired if I might ask her some more questions the following day, either here or at her law office. I expected she might decline, reasonably enough. Already she had been generous with her time. To my delight, she invited me to stop by her office.

Terrence and I bid her good night and slid into the rental car. We drove back to the motel, excited by this unexpected development.

The next morning, I called my editors. We agreed it made sense to stay on. Alice speaking on the record, particularly about their parents and her sister’s experience with fame, was unusual.

We had another long interview that day, in the suite of offices above the Monroe County Bank. Barnett, Bugg & Lee was a two-lawyer firm consisting of Alice and a young male attorney she had taken under her wing. Another attorney was of counsel. A receptionist sat at a desk near the front door and relayed callers’ messages to Alice. She could no longer hear well enough to use the telephone. As with Atticus Finch and many other small-town lawyers, real estate transactions, tax returns, and wills were at the heart of Alice’s practice.

At one point I asked her about her sister’s long public silence. “I don’t think any first-time author could be prepared for what happened. It all fell in on her,” Alice said, “and her way of handling it was not to let it get too close to her.”

And what about the first question everyone had about her sister: Why didn’t she write another book?

Alice leaned forward in her office chair. “I’ll put it this way . . . When you have hit the pinnacle, how would you feel about writing more? Would you feel like you’re competing with yourself ?”

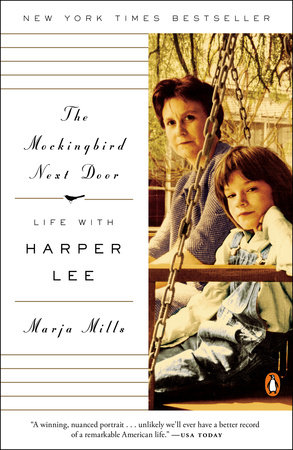

From THE MOCKINGBIRD NEXT DOOR. Used with permission of Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2014 Marja Mills.