DAY 1

I am staring out the window of my office and thinking about death when I remember the way Paiute smells in the early morning in the summer before the sun burns the dew off the fescue. Through the wall I hear the muffled voice of Meredith shouting on the phone in laborious Arabic with one of her friend-colleagues, and in my mind’s eye I see the house sitting empty up there, a homely beige rectangle with a brown latticed deck and a tidy green wraparound lawn to its left, a free-standing garage to its right, and beyond that an empty lot with juniper shrubs and patches of tall grass where the deer like to pick. Technically it is a double-wide mobile home, although it does not look mobile—it’s not on wheels or blocks; it has a proper covered foundation, or at least the appearance of one, and could not be mistaken for a trailer. Technically I own this house, because my grandparents left it to my mother and when she died she left it to me.

The house is waiting for an occupant; my uncle Rodney, who didn’t need it and thus didn’t inherit it, has been paying someone to come every month to tend the geraniums and cut the grass for the last five years. He pays for a low, persistent hum of electricity and gas through the winter so as to avoid the effects of a hard freeze. The idea is that someone will one day want to buy this house, and my uncle Rodney is keeping it nice until then, I suppose as a favor to me.

I hear Meredith send valedictory kisses through the phone and amid the sparkling glass and chrome splendor of the Institute I see the faux-wood paneling of the house and the nubbled brown upholstery of my grandmother’s two soft couches, still in situ with the rest of her furnishings. And then I feel something tugging—first from across the Bay, the dingy living room where Honey and six other babies spend ten hours a day toddling, then from the long stretch of road, nearly four hundred miles of road, leading up to the high desert. And then I stand up from my office chair and open the right-hand desk drawer and put a Post-it on the petty cash box noting my outstanding debt of $64.72 to the petty cash fund, and after a moment’s hesitation I put the Dell laptop and charger paid for with endowment income from the Al-Ihsan Foundation into my bag. And then I turn off my monitor, slip on my ill-fitting flats, call goodbye to Meredith (“Have a good night,” she calls back, at 10:00 a.m.), and walk out of the building and down the main walkway through campus, the Bay before me and the clock tower at my back.

“In my mind’s eye I see the house sitting empty up there, a homely beige rectangle with a brown latticed deck and a tidy green wraparound lawn to its left, a free-standing garage to its right, and beyond that an empty lot with juniper shrubs and patches of tall grass where the deer like to pick.”On BART I stare out the window and consider why it is that I am homebound at 10:15 in the morning with my eye to the northeast. The morning was not worse than most mornings. The alarm went off at six and I hit snooze six times at 6:10 6:19 6:28 6:37 6:46. Honey called from her crib like a marooned sailor and I guiltily left her there to take a shower after calculating the number of days without, four, too many. Then half-dressed and still dripping I pulled her wailing from the crib and wiped her tears changed her diaper replaced her jammies gave her kisses carried her to the kitchen. I put her in the high chair and gave her a fistful of raisins and realized there were no eggs or yogurt or fruit, which meant oatmeal, which takes an additional eight minutes by the most optimistic estimate, and so because of my own late start and the absence of the eggs I had to rush her through breakfast, and lately she hates to be rushed, hates to have things cleared away before she is ready, so when I took the oatmeal away she started wailing and when I carried her into our room she screamed and stiffened and threw her body back against my arms, a great dramatic backward swan dive with no regard for what ever might lie behind. And when I hustled her onto the floor to get dressed and held up the onesie and tried to invest her in the process like they say you should she started shrieking and thrashing anew and it felt very distressing, very critical, very personal, and I gripped her arms tightly, too tightly, arriving at a threshold of tightness that felt dangerous but obscurely good in a way I wouldn’t care to investigate further. And then I tugged the onesie over her head looked at the time put my own head in my hands and sobbed for thirty seconds.

Engin’s primary criticism of me is that whenever he tries to initiate a serious conversation I start crying, which activates his innate gallantry and sympathy, and which effectively halts what ever potentially challenging conversation we are having. He calls it a taktik; I call it a refleks. “What do you do when they criticize you at work?” he asked me once, and I told him, truthfully, that at work I am perfect. What ever the thing is, my taktik or refleks, it worked on Honey, because she paused and I seized the moment to stuff all her limbs into the onesie the pants the socks. Then I put her down and got dressed while she rampaged cutely around the bedroom and messed

with the doodads on my bedside table, evil eyes and icons and various other apotropaics I keep meaning to hang up on the wall. And then I dutifully put the little rice-size grain of toothpaste on the little toothbrush festooned with Elmo and friends and sang the song from the Elmo video, but she clamped her mouth shut tight and pearly tears squeezed from her eyes and I gave up which I do four times out of ten.

But all this was par for the course. In fact it was a small miracle that we were out the door at 7:55 for a nearly on-time daycare arrival of 8:05. Then to the streetcar, then to the train, there to zone out with the Turkish work of midcentury social realist fiction I’ve been trying to read for three years, then switch trains, then to the planter boxes of a Wells Fargo to smoke a cigarette, then up the hill to arrive at work at 9:35 which is a little over one hour later than I am supposed to be there according to the terms of my offer letter. But I’m still the first in the office, and if I bring Honey to daycare at 8:00, the earliest they accept kids, I can’t get to work any earlier than 9:30, even if I don’t smoke a cigarette—it is physically impossible.

In the office things had proceeded more or less as usual. I visited the Visa Status Check page of the National Visa Center website to see the status of Engin’s green card, which was, is, in perpetuity, “At NVC,” which means nothing except that not a single thing that needs to happen has happened. I checked the bank balance, $341 checking; $1,847 emergency. This had five months ago been a plump and hopeful $4,147 until the forced abandonment of Engin’s green card and immediate forced return of Engin to Turkey at our expense, and the subsequent retention of an attorney to reapply, and the new application fee, and the recent additional lawyer’s fee to understand why it has been At NVC for five months with no perceptible forward movement— which is, we have lately been told, a probable “click-of-the-mouse error.” I paused to silently pray that what ever future emergencies might arise can be resolved for under $1,847. I checked the credit card balance, $835 less $483 in pending reimbursements for Miscellaneous Catering Expenses. I checked the University Purchasing Portal to see the status of my pending reimbursements, and verily they were still pending. I checked my retirement balance, $9,321, which was theoretically comforting although I cannot of course access it without penalty for twenty-seven years. I checked an immigration thread on BabyCenter, very short, and a Subreddit, very sad. I looked at a WeChat picture from daycare showing Honey’s diaper and a troublingly small turd. I checked Whats App for Engin’s last greeting and sent him the picture of the turd. And finally I listened to a voice mail from the Office of Risk Management relaying that I would have to make a statement regarding the death of student Ellery Simpson and injuries sustained by student Maryam Khoury in a taxi outside the Fidanlik Park refugee camp on a research trip supported with funds from the Al-Ihsan Foundation and partially arranged for by me. And then I looked out the window and thought of death and remembered the smell of the Paiute air and the dew on the fescue grass.

*

I reach my stop and take the streetcar to my block and stop to smoke a cigarette in front of the door of our building, staring at a free newspaper in a waterlogged bag on the pavement and picturing the long road up to the house. It’s been a year since I made the drive, the miles of sprawl, then the huge swath of territory punctuated by alkali lakes and picturesque homesteads and tree stands, then the stretch of increasingly far-apart tiny townships and ruined general stores and abandoned trailers, the place where you think you’ve absorbed the beauty and caution of the territory and it must be time to get where you’re going but you’ve still got eighty miles of rattlesnake plain left to go. I imagine the swift elevation up from the plain through sugar pine and juniper and more pine and the sudden descent onto another great basin, this one checkmarked with fields and cattle and pieces of wetland, its silvery grass and wet places shimmering pink in the twilight, a cattleman’s paradise five thousand feet high. And then my own abandoned homestead in Deakins Park, to sink into those soft nubbled couches and take in the cool morning air of Altavista, the seat of Paiute County.

I put out the cigarette in a flowerpot and go inside and pull out a tote bag and a suitcase, and all of the focus that has lately abandoned me at work materializes and I run through the checklist: clothes diapers Pack ’n Play baby bedding sound machine high chair Ergo stroller toys books bib sippy cup snacks and, in a flash of motherly inspiration, socket protectors. There are thirty-some Costco string cheeses in the fridge and several bags of shriveled horrible natural apricots in the cupboard. I put on jeans and I stuff my jammies a house dress a few of Engin’s T- shirts and my sweatshirt that says “I Climbed the Great Wall” into the suitcase. There is no Business Casual in the high desert and none of my nice things fit in any case. I put everything in the trunk of the car in two trips and then I pause before locking the door and run back in to get our passports because you never know. Then I stand on our dingy wall-to-wall carpet thinking now is a moment to reverse course and drive south to the airport and find the soonest flight to Istanbul and get us one ticket since Honey is still free and then I recall I have this thought every single day like a goldfish and every time it ends back at the $1,847 in emergency.

“It’s been a year since I made the drive, the miles of sprawl. . . the place where you think you’ve absorbed the beauty and caution of the territory and it must be time to get where you’re going but you’ve still got eighty miles of rattlesnake plain left to go.”My mother-in-law is not rich but she is not poor and I suspect she would happily buy the plane ticket to get her hands on her granddaughter so I suppose it’s not only the $1,847 that keeps me from this course. The other thing is that I have this objectively marvelous job, a world-historically good job, a job at one of the best universities in the country or the world, a job wherein I got to make up my own nonsense title which is Director of Engagement and for which I make $69,500 a year all by myself, an extremely arbitrary figure which is somehow not enough to live on here but well above the national median house hold income and with which I pay our rent our daycare and our food and appreciate but do not rely upon the sporadic lump sums from Engin’s video gigs. “Always have a job,” my mother told me when I was eleven, and again when I was seventeen, and then again, when I was twenty-three, right before she died, when we sat together at her dining room table going over the papers that would give me the mobile home and all of her own furniture and household effects. “Don’t ever live on someone else,” she said to me over her glasses, her dainty head wrapped in a silk scarf I remember for no reason that my dad bought her at the Alhambra gift shop in the dead of a cold Spanish winter.

So I suppose it is the $1,847 that keeps me here, but it is also my glass-walled office, my gold-plated health care, our below-market rent in a top-five American city. And there’s Honey, born here. If we leave I am pretty sure we are never coming back, and she’s a California baby now and if we leave she won’t be ever again. So I abandon Istanbul with a pang as I do every time I think to take flight, and I smoke another cigarette against the hours in the car to come. Then I walk the two blocks to daycare to collect Honey, who gives me a radiant smile when she is brought to the door, which I accept as confirmation of the rightness of my actions thus far.

__________________________________

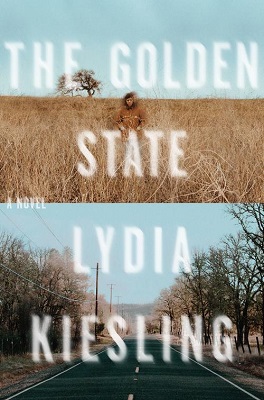

From The Golden State. Used with permission of MCD Books. Copyright © 2018 by Lydia Kiesling.