Under the Apple Tree

When Joe left me sitting under the apple tree and started to walk across the pasture, he looked back and waved, and then walked on, and then turned and waved, and then walked on, and then he did a complete circle with his arms out, like he was embracing the world. That made me laugh because we were both so happy and so willing to show it. I was leaning back against the tree, most of my clothes back on, wrapped in a blanket, and I watched him go in his spinning cheerful way, and I blew him kisses. Then he got near my trailer and dirt driveway, which is where he’d left his truck, and he climbed in, honked, honked again, and left.

We’d just made love and we’d both come twice, and my body was feeling full and complete and tired. The contrails from the flying sparks of orgasm were just starting to fade, and I felt them dissipate into the space of my body. As they did, I picked twigs out of my hair and wiped a smudge of dirt from my forearm and let my mind think things like, the only thing grand enough for a human life is to love and this is where wild and gentle get sewn together, and the sorts of things that make perfect sense at a time like that, and only at a time like that, and I just sat still and let them.

When he was gone, I considered the sharp rotting smell of apples, and the slant of cold sunlight on my bare feet, and the ache of my knees and inner thighs. After some time, I walked toward my trailer home, bundled up in my blanket, spinning around by myself, and once inside, I flopped on my bed, and I closed my eyes and replayed the whole thing—our lovemaking, and my orgasms, and his, and our mumblings. Then my mind wandered on to less romantic things, like the fact that my rear is dimpled with fat, but I like that position; and that perhaps I had said a stupid thing or two, which was too bad, but entirely predictable. I rubbed my head where it had hit the apple tree, and I brushed away the bits of earth still smashed against my spine.

Joe and I have the exact same hair color—so dark brown that it’s almost black, only his is curly and mine hangs straight to my waist. Our hair is graying, Joe near his temples and mine spread all throughout, and his is softer than mine, because the gray in mine has turned it less supple. I thought of our hair, and each other’s hands in our hair, and I made myself come again. I was curious if I could accomplish three, which is something I hadn’t done before. When my body stopped pulsing, I decided that orgasm is the greatest physical pleasure in life—greater than the feeling of being high, being drunk, feeling sunlight, touching water, catching a snowflake, or the taste of something sweet or salty or new, and that this had to be especially true if one was being held at the same time, and being kissed, and being loved.

* * * *

I live too hard and I know it. Every once in awhile I get myself into some trouble because of this but generally, over the course of my life, I have come to believe it’s worth it. I drink too much, I smoke too much pot, I sleep around. That sort of thing. My body and heart are getting beat up faster than they should be, but I won’t regret this life as much as some people will want me to.

I have one bias that I cannot rid myself of. Perhaps we all ought to be allowed to have just one, and mine is that I severely dislike stingy people. By this I mean not only in the cash sense, but in the people of the world who aren’t generous with their thank yous or their I’m sorrys and most importantly, with the people who spend so little time thinking about others, so little energy loving. I do not like miserly hearts.

Which is probably why I like Joe so much, because he is, at the core, generous. He is, for example, willing to walk away from his new lover, and tell her goodbye in the most charitable way he can, by spinning and holding his arms out to the world. He is announcing: life is good, that was good, I love you. That is something, really that is something.

I am a housecleaner. I sell pot on the side, even now that it’s legal, because who wants to drive to town when they know I’m here, on the mountain, and a good grower? My goal here is to make a living as quickly as I can, so I can spend the rest of my day hiking, or snowshoeing, or reading, or with Joe and his body, or inside my brain, with Joe and his body. The only other interesting thing I can say about myself is that I’ve always been fascinated by sex; which is not to say that I’ve engaged in a huge amount of wondrous activity, but rather that I have paid attention to sex the way some people pay attention to racecar drivers or sports teams. If there were a column in the paper, it would be the first I’d turn to. I know about the Hite Report and Deep Throat and I know about Candida Royalle porn. I know what Freud and Foucault have to say, and I know the most basic truth about enjoying sex, which is that it’s part instinct, but mostly, it’s concentration, it’s a learned activity.

It can’t be learned with just anybody, though, and I’m beginning to think that’s what’s going on with Joe. That is why losing him scares me. He’s going to open me right up, make me understand and feel, and then the loss will be one that I’m not strong enough to bear. He will get in his truck and drive out of my life, back to his horseshoeing and his mountain walks and his hunting and the things that do not include me.

* * * *

Anya’s two kids are always coming over to my property to pick apples. Anya is my one friend, and she’s also my only neighbor way up here in this mountain enclave. We have a remarkable friendship, really, and I love her. Anya has short blond hair, which she dyes, and she’s married to the town vet, and she’s a therapist, and she’s got these two kids and she exercises and she eats right, and so in many ways, Anya is the opposite of me. That’s why we’re friends, at least in part, so that we can see the other life, the road not taken; we can bounce into that every once in a while without having to live it ourselves.

The apple tree sits right between our two houses, with about an acre on each side, and the tree lures her kids onto my place, which is more overgrown with raspberry bushes I planted, and the milkweed and mountain mahogany and grasses that nature did. I tell her kids to watch out because there’s a bear. His scat is all over the place, big dumps of apple-seed laden piles. I haven’t actually seen the bear, but sometimes I can smell it, the vinegar smell of its urine, the rank smell of the body. The kids need to be careful, and I tell them this, but they escape out of the house, right when Anya is trying to put bread in the oven, for instance—she is a great baker—and these kids were meant for the outdoors and I think that’s great but I worry about the bear.

Anya thinks I’m amusingly wild and I like regaling her with stories, and so when she came over for our five-o’clock whiskeys, which is something we do every-other-day, I told her about Joe. How Joe’s kisses had a certain pull to them, his hands had a certain knowledge, how his fingers listened. I told her that it was startling to suddenly, at this age, be experiencing such orgasms. Orgasms that came so easily, with the muscle contractions spreading through my body with unexpected lightness and force, great crashes of sparks that danced as they shot from my inner regions to my skin.

Anya stared at me a long time. She said, “Sy and I never have sex like that. Maybe we never did.”

I could hear the waver in her voice, so I said, “Well, there’s a lot of days when I wish I had one particular person. And that I had kids. I don’t have anyone to sleep with me at night.”

We sat for a while and ate some of her homemade bread with Havarti cheese and the last of this year’s raspberries.

“Can I ask you something?” I finally said. “When you orgasm, during sex, you’re telling yourself a story in your head, right?”

Anya tilted her head and considered this. Then she chewed on her thumb and thought about it some more. “That’s probably true.”

“Can you orgasm without it? Without a story going on in your head?”

Her eyes moved across the pasture, as if the pasture was the landscape of her brain, and she was examining the horizon for memories and experience. “I don’t think I can. I think I need the story. I’ll pay attention to confirm that for sure.” She stuffed some bread in her mouth and looked up at the sky.

“Because I couldn’t. Without a story,” I said. “But then, with Joe, I suddenly could. I mean, it’s ridiculous! It sounds like a romance novel! It sounds like I’m one of those women doing a disservice to womankind by granting the man too much, by having too much pleasure, by exaggerating the possibilities. I just want to store these moments up for later.”

“That’s sounds smart. Have another drink.”

“I’ve had bad sex before,” I said. “Plenty of it. Bad sex, mediocre sex, standard sex. But suddenly this. It’s confusing my body, and I just didn’t expect that kind of surprise.”

She said, “Joe sounds better than any of your previous choices. Maybe you should figure out a way to make this work.” Anya chewed on her lip and I could tell she was telling herself all the things she didn’t like about my life, so she could confirm her choices. As part of her righting of herself, her eyes veered off to her kids, as if to say, There, that’s what you have, there they are.

After she was done looking at them, I said, “Can I ask you one more thing? These stories, the ones we tell ourselves, they have violence in them, don’t they? Spankings? Forced blow jobs? Being tied up?”

Anya raised her eyebrows and then laughed. “Yes.”

I said, “I think most women do. Link violence and arousal. What’s that all about? Some buried remnant, some cultural leftover. But here’s what I’m getting at. I was thinking about this while I was cleaning today. Humans are going to evolve. Someday, when you and me are long gone, you know, humans will be different, they’ll change for the better. One, they’re going to figure out how to communicate on a higher level. Two, they’re going to be able to see another person better. Because three, they’re going to be able to see inside themselves better, with some clarity. And four, this violence, it’s going to disappear. For some women, it’s just not going to be inside anymore.”

She gave me an endearing look and said, “Gretchen, that’s very optimistic of you.”

“I know,” I said.

“You’re seeming very young today,” she said.

“I know,” I said. “I know.”

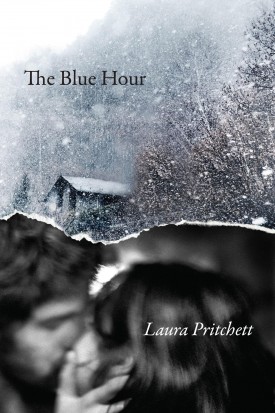

From THE BLUE HOUR. Used with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2017 by .