Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels, the best short story collections, the best poetry collections, the best memoirs, the best essay collections, and the best (other) nonfiction of the decade. We have now reached the seventh list in our series: the best novels translated into and published in English between 2010 and 2019.

Each of these lists has presented its own set of problems; with this one we worried about whether it was somehow condescending to books in translation to give them their own list (especially considering they do appear on many of the linked lists above). But in the end, considering that books in translation still make up only a tiny percentage of the books published in English every year, we figured it was worth highlighting some of our favorites. (We stuck to novels because that was the biggest group.)

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

***

The Top Ten

Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky, Visitation (2010)

Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky, Visitation (2010)

At the center of this extraordinary novel is a house on a lake, surrounded by woods. The house and the lake and the woods are in Brandenburg, outside of Berlin. People move in, through, and around the house, and time moves in these ways too—the novel is set during the second World War, and before, and after. The realities and their attendant characters—the gardener, the architect, the cloth manufacturer, the red army officer, the girl—are layered elegantly on top of one another, creating a sense of pattern, of fugue, more than of traditional narrative. As in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the house itself becomes the central, if mute, figure of the novel, and time itself its essential subject: what it does to us and to the world, how we remember, and how we don’t. And also like To the Lighthouse, there are little human dramas within this grander and colder scheme, ones that secretly hook us in, however minor they seem, so that we are devastated when time passes, so that we mourn the ones we barely knew, for their fixations, their tragedies, their trying. Elegiac, often astoundingly gorgeous, sometimes strikingly brutal, this is one of the most wonderful novels of any sort that you could hope to read. P.S. this novel edged out Erpenbeck’s more recent novel, Go, Went, Gone, also translated by Susan Bernofsky, for this list, but we also very much recommend that one. Really you can’t go wrong by immersing yourself in the work of these two masterful artists. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, My Brilliant Friend (2012)

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, My Brilliant Friend (2012)

Before I read My Brilliant Friend, the first of Elena Ferrante’s four Neapolitan novels, I was told by several colleagues that the books were written pseudonymously. All I knew was that they are autobiographical, chronicling the lives and friendships of two young women, Lila and Elena. This conversation took place before the 2016 press attempt to expose Ferrante’s real name, and so someone in the group mentioned that they wondered if the real author of those female-centric stories were a man. Another colleague (a woman) responded quickly, “Absolutely not,” and added “they are written by a woman. You can just tell. They understand women in a way only a woman can.”

Translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein in 2013, the Neapolitan novels (and My Brilliant Friend, particularly, since it broke the ground) are so perfectly, beautifully intuitive. They are about women’s voices—what it means to be a woman and to have a voice as a woman—but also the ways women speak and not speak and who they sound like when they do or don’t. My Brilliant Friend introduces Lila and Elena, childhood friends, as the two bright starts in a depressed Italian neighborhood—precocious readers and writers. They each are beautiful and compelling, but they take different paths. Elena becomes a writer. Lila should have become a writer. My Brilliant Friend is wise, it is nostalgic, it is wistful. But more importantly, it is a love story—between the two central friends, yes, but also between each woman and herself. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Marie NDiaye, tr. John Fletcher, Three Strong Women (2012)

Marie NDiaye, tr. John Fletcher, Three Strong Women (2012)

Published in France in 2009, Three Strong Women won the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary award, making Marie NDiaye the first black woman to have ever won the prize. Having already written Self-Portrait in Green, a wonderful, experimental memoir, and later to publish Ladivine, which was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, NDiaye has by now established herself as a significant, international literary prose stylist and playwright. One can look to NDiaye not only for well-rounded, complicated portraits of characters but for her “fantastical narratives,” as The New York Times writes, in which “the destabilization and even duplication of the self occurs frequently, particularly in families.” Three Strong Women is structured in three parts and moves between France and Senegal to accommodate the stories of Norah, Fanta, and Khady, three women whose resilience and self-worth is called upon to deal with the men of the world who are trying to control and subjugate them. Norah, a lawyer born in France goes to Senegal to deal with another of her father’s offspring; Fanta must leave the teaching job she loves behind to move to France with her husband, where she will not be able to teach; and Khady, a penniless widow, must take to France, where she has one distant cousin, to save herself. Told with incisive wit and deep dives into her characters, NDiaye’s narrative is completely immersive and invokes empathy, and humanity juxtaposed against the toxic masculinity that often plagues families; fathers and daughters, husbands and wives are often at odds in NDiaye’s works, meanwhile the matrilineal line reigns as a force of strength, unending support, and guidance. NDiaye’s ability to invite the reader into the lives of her characters is peerless, and for me, her symbolism and imagery—that verges on surreal or hallucinatory at times—deepens and complicates the layers of the themes of identity, womanhood, lineage, inheritance, and responsibility which she explores with utmost elegance and force. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Juan Gabriel Vásquez, tr. Anne McLean, The Sound of Things Falling (2013)

Juan Gabriel Vásquez, tr. Anne McLean, The Sound of Things Falling (2013)

Gabriel Vásquez has long since established himself as one of the leading voices in Latin American fiction, with a career now spanning two decades and including the 2004 breakout Los informantes, but it was the release of El ruido de las cosas al caer in 2011, brought out two years later in the US as The Sound of Things Falling, that cemented his reputation as a giant of international letters. The novel’s aims were at once ambitious in scope and intensely particular, even intimate. Gabriel Vásquez summarized the project in The Guardian after winning the International Impac Dublin award: “We had all grown up used to the public side of the drug wars, to the images and killings … but there wasn’t a place to go to think about the private side … How did it change the way we behaved as fathers and sons and friends and lovers, how did it change our private behavior?” The narrator and ostensible protagonist of The Sound of Things Falling is Antonio Yammara, a Bogotá law professor whose proclivities make a mess of his current circumstances and drive him to look back on his own and Colombia’s recent past. It’s a life whose texture is often distorted by the effects of narco-trafficking and an increasingly chaotic and violent culture. The story splits out through several time strands, conundrums, and characters, including most notably an ex-con in a pool hall who leads Yammara down a mysterious path and sees both men gunned down on the city streets. The nature of memory, identity, and time become Yamarra’s obsessions, but in classic noir fashion he only seems to wade deeper and deeper into the abyss. Obsession takes over life, as Gabriel Vásquez subtly brings out the devastating effects of a society under the extreme tension of decades of corruption. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Eka Kurniawan, tr. Annie Tucker, Beauty is a Wound (2015)

Eka Kurniawan, tr. Annie Tucker, Beauty is a Wound (2015)

Beauty is a Wound—Eka Kurniawan’s epic, polyphonic, multi-genre novel—is the story of the prostitute Dewi Ayu (who returns from the dead in the first sentence of the novel) and her four daughters. Set against the backdrop of Indonesia’s history of colonialism, its independence struggles, and its depredations under Suharto’s despotic rule, Beauty is a violent family saga flooded with incest, murder, bestiality, and rape (a lot of rape). Dewi Ayu, a mixed race descendant of a Dutch East India Company trader (her parents are half siblings), is taken to a Japanese internment camp reserved for Dutch colonists at the start of World War II; there she survives by becoming a whore—the most beautiful, most sought after prostitute ever. She gives birth to three beautiful daughters who marry important, political men. It’s her fourth daughter, Beauty, who is born (as per Dewi Ayu’s wish) “so hideous that the midwife assisting her couldn’t be sure whether it really was a baby and thought that maybe it was a pile” of excrement. The novel’s evocation of fairy tale and fondness for the tropes (and sexual politics) of magical realism are reminiscent of Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and, at times, Rushdie—there are lovers whose kisses create flames and man who, despite many efforts, cannot be shot or stabbed. But the hyperbolic, maximalist voice brought to rapturous life by Annie Tucker’s 2015 English translation for New Directions is thoroughly Kurniawan’s own. Sometimes maddening in its scope and innumerable characters, it’s an exhilarating novel, and one of the best in translation published this decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Magda Szabó, tr. Len Rix, The Door (2015)

Magda Szabó, tr. Len Rix, The Door (2015)

Magda Szabó’s The Door was first published in Hungary in 1987; it wasn’t published in America until 1995, and I didn’t discover it until 2015, almost a decade after Szabó’s death, when it was reissued by the New York Review of Books. I can’t remember why I picked it up, but I remember the feeling I had only a few pages in: that this was a voice unlike any I’d ever read—elevated, almost cold, but bristling with passion beneath the surface—and that the book was very, very good. And I know I’m not alone. “I’ve been haunted by this novel,” Claire Messud wrote in The New York Times Book Review. “Szabó’s lines and images come to my mind unexpectedly, and with them powerful emotions. It has altered the way I understand my own life.”

The plot is simple, even boring. (More and more, I find that my favorite novels defy snappy summation; there’s no clever, alluring way to describe a quality of mind that can only be understood by reading.) Our narrator tells us a story from years before, when she, a writer whose career had been until recently held up for political reasons, hired a woman to help around the house. But she is no ordinary woman, and the novel is the story of their relationship, one which culminates in a truly extraordinary set piece. “It won’t do to say much more about the plot of the book,” Deborah Eisenberg wrote in her NYRB review, “first because the rather white-knuckled experience of reading it depends largely on Szabó’s finely calibrated parceling out of information, and second (though this might be something that could be said of most good fiction) because the plot, although it conveys the essence of the book, is a conveyance only, to which the essence—in this case a penumbra of reflections, questions, and sensations—clings.”

You see—all that’s left to explain is where you can buy a copy, and I figure, if you’re reading this space, you know that already. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith, The Vegetarian (2016)

Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith, The Vegetarian (2016)

The Vegetarian is the most beautiful work of body horror I’ve ever ingested. It makes sense—what is a body if not a beautiful horror? (Too on the nose? Fine.) Han Kang’s first novel to be translated into English, The Vegetarian is divided into three sections and centers around a woman, Yeonge-hye, described by her husband as “completely unremarkable in any way.” Yeonge-hye is the catalyst for the story’s action—in the novel’s first section, her husband wakes up to find her throwing away all the meat in their kitchen because of a dream she had—but the story, which shifts perspective in each section, is never told in her voice. Yeonge-hye doesn’t rebel against erasures of her person. Instead, she leans further into unpersoning. She stops eating meat, which infuriates her family, then stops eating altogether. In the book’s second section, “Mongolian Mark,” Yeonge-hye’s brother-in-law becomes obsessed with her, specifically a birthmark on her backside, and paints flowers all over her body as part of an art project. Even his desiring of her unpersons her. The scene is horrific and beautiful at once, like so much of the novel. Its language is spare and matter-of-fact, which makes the violence all the more unsettling. Porochista Khakpour describes The Vegetarian as “magnificently death-affirming,” and I’m at a loss to do better than that. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Jennifer Croft, Flights (2018)

The book that established Olga Tokarczuk’s name in the Anglophone world could’ve easily been structured and marketed as a book of short stories, perhaps some of them interconnected. But the fact that Flights is a novel seems somehow more true-to-life in the way that our lives, yours and mine, are discontinuous, fragmented, full of returns and departures, progress and regression. When your eulogy is read, who will describe your singular life in terms of chapter breaks and clean divisions? Flights, an apt title wonderfully rendered by translator Jennifer Croft, felt almost like it was eschewing novelty for novelty’s sake. Rather, it pushed against the edges of the novel’s form to make us second-guess whether the form was somehow actually “exhausted.” Tokarczuk’s stories encompass different epochs, locations, lengths, perspectives and tonal registers: a Polish man on vacation searches for his missing wife and kid; a classics professor experiences a fatal fall aboard a boat heading to Athens; a nameless narrator marvels at the potential of a floating plastic bag; a German doctor obsesses over body parts and their preservation. Tokarczuk is working in a similar vein as Italo Calvino in If on a winter’s night a traveler, Georges Perec in Life: A User’s Manual,and Jorge Luis Borges in his short story, “The Library of Babel.” That is, she has an eye for the paradox of the encyclopedic project, which seeks at once to encompass a significant range of information and possibilities while also leaving room for expansion. As James Wood wrote in his New Yorker review, Flights is “a work both modish and antique, apparently postmodern in emphasis but fed by the exploratory energies of the Renaissance.” –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Ahmed Saadawi, tr. Jonathan Wright, Frankenstein in Baghdad (2018)

Ahmed Saadawi, tr. Jonathan Wright, Frankenstein in Baghdad (2018)

Full, potentially compromising disclosure: I’m here for most, if not all, Frankenstein adaptations and/or reimaginings, from the highs of Danny Boyle’s theatrical production to the alleged lows of the 2014 Aaron Eckhart-fronted sci-fi action horror flick I, Frankenstein. Shelly’s novel is, for me, the greatest horror tale in literary history, and I welcome all acolytes, regardless of how clumsy their tributes may be. Saadawi’s unabashedly political, blackly funny contemporary take on the mythos (superb translated by Jonathan Wright, who captures the wry humor and brooding, ominous rhythms of Saadawi’s dark tale) is, however, a true standout in a very crowded field. Set within the tumult and devastation of U.S.-occupied Baghdad, it’s the tale of Hadi—a scavenger and local eccentric—who collects human body parts, stumbled upon or sought out in the wake of suicide bombings, and stitches them together to create a corpse. When his creation disappears, and a wave of gruesome murders sweeps the Iraqi capital, Hadi realizes that he has, ahem, created a monster. What’s so fascinating about Frankenstein in Baghdad—an ingenious tonal blending of conflict reportage, mordent satire, gruesome horror, and tender travelogue—is that, like its malevolent star, the book’s effectiveness lies in its patchwork nature. There’s something awesome and terrifying about watching this abomination’s unlikely rise from the operating table, its ability to wreak havoc with a conjured power far greater than the sum of its disparate parts. As Dwight Garner wrote in his New York Times review of the book: “What happened in Iraq was a spiritual disaster, and this brave and ingenious novel takes that idea and uncorks all its possible meanings.” –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Can Xue, tr. Annelise Finegan Wasmoen, Love in the New Millennium (2018)

Can Xue, tr. Annelise Finegan Wasmoen, Love in the New Millennium (2018)

We quickly learn that nothing is as it seems in Love in the New Millennium, a book by experimental Chinese author Deng Xiaohua, known by her pseudonym Can Xue. This is a work ostensibly about love stories. Not much “happens” in the sense of a through line from points A to Z, which is the draw of this perplexing book. Translator Annelise Finegan Wasmoen conveys a remarkable linguistic simplicity while maintaining the weirdness of Xue’s descriptive passages and dialogues, which are rather like non-sequiturs, fragments of barely connected thought that make us think they are meant to follow from one another because they are framed a certain way on the page. There’s a little passage in a chapter about an antique store owner named Mr. You that sums Xue’s book up well. Speaking of Mr. You: “His personal life was hardly smooth sailing, but there were no life-or-death crises. His nature quietly settled into shape apart from anyone’s notice […] A stranger looking at Mr. You would have seen no trace of time’s passage on that face—he looked too much, in fact, like someone a little over thirty.” If there is a crisis at all in the book, it’s that minute changes are often happening quietly, such that characters and readers might easily miss them. Each of the book’s chapters are often narrated by one or two new characters, one being at least tangentially connected to the next. Movements of time are questionable, and just about every encounter in some way minor. This is a challenging but worthy path into Xue’s body of work. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

***

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Don Bartlett, My Struggle: Book 1 (2012)

Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Don Bartlett, My Struggle: Book 1 (2012)

In retrospect, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle saga is perhaps best understood as a literary phenomenon of the internet age. The sense of selfhood that obsesses it is so monomaniacally focused, so deeply confessional, premised on a disclosure so radical (the author’s father’s abuse, alcoholism, death; his wife’s nervous breakdown) it infamously cost Knausgaard some of his closest personal relationships even as it won him international acclaim. Added to that, the suspense and anticipation on which the series’ rising acclaim in the English-speaking world depended was a pleasure its readership had almost forgotten it could feel. Somewhere, out there, were very large books—very large caches if information, of personal data—bound and in physical form but inaccessible to you, the next volume unavailable for another year! And when the work did become available, there was the sheer superabundance if it, the excruciating detail its author expected you to be interested in—or maybe what he expected you to be was bored. And why would someone want to bore you like that; who was this guy? And what was with the title? What kind of “novel” was My Struggle—or what could it be, a book that so undid the notions of the form (plot, characters, development) as to seem at once to portend the total destruction of the novel and the next stage in its next evolution. In the end, seven years, five more volumes, and one 400-page not-okay digression on Hitler (Book Six) later, the sum of Knausgard’s achievement feels less than what this first volume promised it could be. But what a promise it was. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Fuminori Nakamura, tr. Satoko Izumo and Stephen Coates, The Thief (2012)

Fuminori Nakamura, tr. Satoko Izumo and Stephen Coates, The Thief (2012)

Fuminori Nakamura is one of the most intriguing crime writers around, and in 2012, SoHo Press began a decade of bringing his spare, minimalist prose and intellectual noir aesthetic to American audiences. The Thief is a perfect noir—we follow an unnamed protagonist as he wends his way around the cityscape, thieving and thinking, until he encounters a shoplifting child and saves him from arrest. When the titular thief meets the child’s mother, he finds his hard edges softening, and in the process, finds himself less and less suited to the life of a desperado, and increasingly vulnerable to the dangers of the streets. Japanese noir, with its frequent emphasis on alienated cityscapes and the difficulty of human connections, has always appealed to me, but The Thief is the ultimate example of noir distilled to its essence. Nakamura writes harsh poetry for the modern world, and his works are essential reading for fans of translated works and just plain literature alike. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Valeria Luiselli, tr. Christina MacSweeney, The Story of My Teeth (2013)

Valeria Luiselli, tr. Christina MacSweeney, The Story of My Teeth (2013)

Valeria Luiselli’s short novel The Story of My Teeth, written in Spanish and translated by Christina MacSweeny, was produced in collaboration workers at the Jumex Juice Factory in Mexico. She would send chapters of the novel to the juice factory workers, who would read, discuss, and provide feedback on the story in a kind of book-club format. Then the writing project was commissioned in conjunction with an art exhibit, called “The Hunter and the Factory,” which was installed in the juice factory, itself. The Story of My Teeth was originally included in the exhibition catalog—Luiselli eventually expanded it into the full novel later. This background, which she presents in the novel, makes perfect sense, given that The Story of My Teeth is about the incredible meaning of objects—not merely as symbols, but as transformative, personal, material things, whose very materiality has the most significance.

Told in seven parts, it tells the story of Gustavo (“Highway”) Sánchez Sánchez, a compulsive liar, flamboyant auctioneer, and a collector of teeth from famous people (including Plato, Petrarch, G.K. Chesterton, and Virginia Woolf). He trades all these in to buy a pair of teeth that purportedly belonged to Marilyn Monroe, which he then has implanted into his own mouth. He is kicked out of his son’s house and set adrift, and wanders. That’s all there is to the story, except it’s also not—while the narrative concludes, the book picks up in a series of photographs and a “Chronologic” (this one drawn by Christina MacSweeney, the novel’s translator—additionally emphasizing the true collaborative spirit of the project). The book is about relics—the morsels of things that last throughout time, and are imbued with great significance specifically for being lasting material things. The book itself plays with its being an object—there are marbled paper pages printed into it, whole pages which are devoted to reproducing fortune cookie fortunes, photographs, illustrations, a map. In this way, it reads much like Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, which also experiments with a book’s ability to be an object, as well as a character’s own awareness that he is literally writing a book (Sterne, a printer who published his own book, also formatted it creatively, slipping in blank and marbled pages on purpose, among other things). It’s a clever, delightful, expanding-center of a book, one which draws on centuries of inquiry about what books are and what they can do. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Kamel Daoud, tr. John Cullen, The Meursault Investigation (2015)

I’m a huge believer in culture as an ongoing conversation, and many of the most beloved works in history are also intensely problematic; so much so that in order to continue loving what’s good about the original, we first need to see a response to its ugliest parts. Kamel Daoud does this in spades with his lyrical reworking of Camus’ The Stranger; told from the perspective the unnamed Arab’s brother, Daoud takes us long past the events of the stranger to take on a sweeping tale of identity and vengeance against the backdrop of the Algerian Revolution. By focusing on the story of Meursault’s victim and his family, Daoud restores humanity to a character used as racially insensitive plot device in Camus’ original, and helps us to understand that Camus’ pretension at distance and invention of “existentialism” was merely another version of colonialist prejudice. Here’s hoping that future schoolteachers take heed from Daoud’s text and change up the way they talk about The Stranger! –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman, Signs Preceding the End of the World (2015)

Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman, Signs Preceding the End of the World (2015)

Signs Preceding the End of the World is a slim novel, barely over 100 pages, and it is almost fable-like, both in length and tone: when you begin reading it, you’re not sure (or at least I wasn’t) whether you’re in our world or another—it begins with a sinkhole, a curse, and a quest. Soon it becomes clear that this is our world, or almost, sliced by the border between Mexico and the United States. Borders in this novel—between worlds, between words, between people—are both dangerous and porous, messages meaningless and profound in equal measure. It is an intense, indelible book, an instant myth of love and violence.

Most of the time, when reading books in translation, I do not stop to wonder what the text was like in its original form; I simply accept the book whole, as it is, while knowing it is in some sense inexact. With this novel, however, I found myself pausing, turning sentences over, wondering how their texture had possibly been transposed from the Spanish, wondering what had been lost, what gained. This should not be taken as a slight against the translator, Lisa Dillman, but rather a compliment: the language is so beautiful and strange and precise, such a perfect balance of high and low, that it seems absolutely native to the book, which is of course about translation in some essential sense itself. I suppose I simply need to learn Spanish, so I can read it anew again. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Fiston Mwanza Mujila, tr. Roland Glasser, Tram 83 (2015)

Fiston Mwanza Mujila, tr. Roland Glasser, Tram 83 (2015)

I would love to have an en face version of this book, to figure out how, exactly, translator Roland Glasser managed to transpose Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s profane and teeming portrait of a semi-fictional Congolese mining town into the roiling, musical English of Tram 83. The novel takes its name from the café-bar-club-brothel at its center, a true demi-monde populated by miners, musicians, malcontents, pimps, gamblers, adventurers, freedom fighters… and, in but a fraction of Mujila’s accounting:

…organized fraudsters and archeologists and would-be bounty hunters and… human organ dealers and farmyard philosophers and hawkers of fresh water and hairdressers and shoeshine boys and repairers of spare parts and…

Bearing witness to this endless stream of characters is Lucien, a writer not infrequently found adrift at the corner table, and the closest thing the novel has to a moral compass. As civil war rages at the indistinct edges of the map, Lucien reenters the atmosphere of his old friend Requiem, a lapsed communist turned black market realist who plays foil to Lucien’s delusions of conscience. It is hard to say who has the clearer picture of the fallen world within which they dwell, the storyteller or the smuggler, but conjured as it is in Glasser’s translation, Mujila’s world will stay with me for years to come. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Álvaro Enrigue, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Sudden Death (2016)

Álvaro Enrigue, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Sudden Death (2016)

I have, from time to time, been accused of only liking “cold” literature. Writers like Tom McCarthy, W. G. Sebald, Rachel Cusk, David Markson, whose primary pleasures (one could argue) are intellectual, not emotional. I will not deny it. (Well, I’ll deny the “only,” maybe downshift it to a “primarily.”) I’d personally much rather be dazzled by prose and form than fully convinced of a fictional character’s personhood and traumatized by their love affairs over a few hundred pages. And those who feel the opposite may not go in for Álvaro Enrigue’s amusing, ramshackle, hyper-intellectual, mischievous tennis match of a novel, Sudden Death, but those with similar proclivities should pick it up immediately.

It is more or less half about an imaginary game of tennis played between Caravaggio (yes, the painter) and Quevedo (the poet), who are using a tennis ball made out of Anne Boleyn’s hair (why not), and half a smattering of other historical musings and anecdotes (one of the most striking is the story of Cortés and La Malinche), with all the timelines thrown together, including some of our current ones (this novel includes emails written between Enrigue and his editor).

None of it makes any overarching sense, exactly, and the many moving parts don’t quite fit together, but they don’t need to. Each one is sheer delight and obvious brilliance, which makes the experience of reading this novel something of an intellectual thrill, and that is more than enough for me. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Andrés Barba, tr. Lisa Dillman, Such Small Hands (2017)

Andrés Barba, tr. Lisa Dillman, Such Small Hands (2017)

Andrés Barba’s Such Small Hands will haunt you. It begins, “Her father died instantly, her mother in the hospital.” This is how we are introduced to seven-year-old Marina, left parentless after a horrible car accident. But the story isn’t so much about the tragedy as it is about the ways she copes with it, starting with language. The first section has her repeat that horrible first line many times, like a refrain. From the concerned paramedics: “But the girl doesn’t cry, doesn’t erupt, doesn’t react. The girl still inhabits the suburbs of the words.” The suburbs of the words!! In Lisa Dillman’s beautiful and biting translation, Andrés Barba gives a physicality to miscommunication and the feeling of dislocation in such a powerful and surprising way. (I read this slender gem of a novel months ago, and I still think of this phrasing often.) Another shiny turn of phrase: “A second later it broke. What did? Logic. Like a melon dropped on the ground, split in one go. It started like a crack in the seat she sat on, its contact was no longer the same contact: the seatbelt had become severe.”

All of Such Small Hands reads like logic breaking, like a melon dropping on the ground. It is the unexpected word choice (the seatbelt had become severe!) that makes this work simultaneously sinister and a joy to read. After the car accident, we follow Marina to an orphanage, where she struggles to find her place amongst the other girls there. In this section, another unexpected turn: the narration starts to switch off, and the reader is met by the collective “we” of the girls who came before her. We (the readers) are brought gracefully into that special realm of make-believe that they have created for themselves, where there exists the real world and the world they all agree on: “We used to touch the fig tree in the garden and say, ‘This is the castle.’ And then we walked to the black sculpture and said, ‘This is the devil.’” Marina eventually finds her place by introducing a menacing game to the orphanage. At only 94 pages, Such Small Hands is a cruelly quick read that makes you feel, in the best way, like the walls of language are closing in on you. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Samanta Schweblin, tr. Megan McDowell, Fever Dream (2017)

Samanta Schweblin, tr. Megan McDowell, Fever Dream (2017)

While Fever Dream, Argentine writer Samanta Schweblin’s mesmerizingly eerie debut novel (novella, really, but who cares), isn’t what you’d call an enjoyable read, it is a remarkably intense and compelling work of existential and environmental dread. A hallucinatory eco-parable clocking in at less than 200 pages, it tells the story of a young woman, Amanda, dying in a hospital bed in rural Argentina, and of the creepy young boy, David, with whom she is carrying on a surreal and fragmented dialogue. Both David and Amanda, as well as Amanda’s missing daughter and the rest of the town’s children, have been poisoned by toxic agricultural chemicals, and while a mysterious local healer saved David’s life, he also replaced half of the boy’s soul with that of a stranger. As you do. And so David and Amanda excavate distressing memories of the recent past together—he the interrogator, uttering the same “That is not important” when displeased, and she the delirious subject, grasping at disintegrating images to stave off nonexistence. As Jia Tolentino wrote in the New Yorker: “The reader begins to feel as if she is Amanda, tethered to a conversation that thrums with malevolence but which provides the only alternative to the void.” The cursed offspring of Waiting for Godot and Pedro Páramo (Juan Ruflo’s iconic 1955 novella about a man returning to his dead mother’s hometown in search of his father, only to find it peopled entirely by ghosts), Fever Dream is a literary haunting of the highest order. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Yan Lianke, tr. Carlos Rojas, The Years, Months, Days (2017)

Yan Lianke, tr. Carlos Rojas, The Years, Months, Days (2017)

Okay, I know picking The Years, Months, Days is sort of cheating because technically it’s two novellas, but I had to champion them somehow because they’ve really stuck with me.

The eponymous novella follows an old man known only as the Elder in his last days of the abandoned village he calls home. A terrible drought has forced the rest of the residents to flee, leaving the Elder and his vision-impaired dog, Blindy, as the sole inhabitants. They become obsessed with salvaging seeds and attempting to grow a new crop for the next season. The bond between the two, the way the dog becomes a way for the Elder to project his thoughts and feelings, is part of what makes this such an interesting story. It is very much a tale about survival, and it will stick its struggling claws in you, much like the second novella, “Marrow,” which tells the story of a widow who will do anything (anything!) to provide a more normal life for her disabled children. She discovers that soup made of bone marrow (especially that of kin) is the solution. She feeds her children soup made of the marrow of their deceased father. It is a chilling story of sacrifice and the lengths a mother will go to to help her children.

It is dark, yes, but there is also something sly and funny in it. It reads like a wink. It feels like a tale being told, like a fable. While the circumstances are dire and shocking, once you enter this surreal world, you might not be surprised at what happens to the characters in it. There is a beautiful, understated repetition to these pages that creates the eerie feeling that you’ve been here before, that you know what’s coming. The prose cradles you in dread. Yan Lianke was the recipient of China’s Lu Xun Literary Prize and the Franz Kafka Award, in addition to being a Man Booker International Prize finalist. His writing, wonderfully translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas, feels like a very old, very magical folktale being passed on to you. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

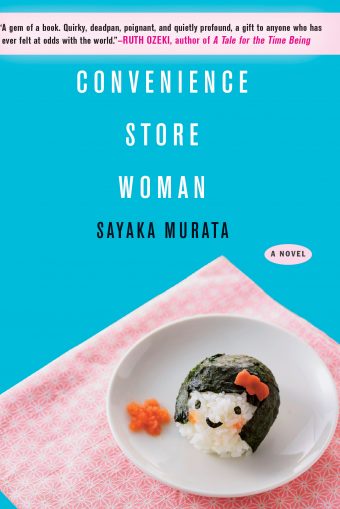

Sayaka Murata, tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori, Convenience Store Woman (2018)

Sayaka Murata, tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori, Convenience Store Woman (2018)

A number of the reviews of Sayaka Murata’s slim, dry, and very funny novel about a 30-something convenience store worker use the word “weird” to describe it. “It’s the novel’s cumulative, idiosyncratic poetry that lingers, attaining a weird, fluorescent kind of beauty all of its own,” writes Julie Myerson in The Guardian. I agree—Convenience Store Woman is weird, in a deeply enjoyable way. Its narrator and protagonist, Keiko, is weird, too—she has been aware, since childhood, of her strangeness, and has taken some pains to cloak her differences (peeking at the labels on a coworker’s clothing in order to imitate her manner of dress, for instance). But Keiko isn’t tormented by her strangeness, and her efforts to conform are mostly so she can live her life unharassed, doing what she loves: working at a convenience store. Keiko’s—and by extension, the novel’s—voice is a clipped deadpan. It’s simple and even repetitive, like the tasks Keiko performs at her job each day, but not monotonous. It reads, by turns, like a love story (woman meets store), an unusually charming employee handbook, and a psychological thriller—but somehow, it never feels disjointed. It was interesting to read this novel in the midst of a glut of English books about the dehumanizing nature of underemployment. Convenience Store Woman doesn’t, in my reading, take a stance on the Value of Work. Instead, it presents Keiko in all her glorious strangeness, and invites the reader to delight in it. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Negar Djavadi, tr. Tina Kover, Disoriental (2018)

Negar Djavadi, tr. Tina Kover, Disoriental (2018)

I am the lover of a certain kind of story, where geographic and interior movement shape one another across various countries and times. This is often explicitly a story about migration and the multiple generations of a family that such movement influences. French-Iranian screenwriter Négar Djavadi’s debut novel ticks these boxes, though it is also a somewhat comic epic about familial fate, sexual awakenings, traditional and unorthodox gender roles, political dissent, and the modern history of Iran. At least one event in Djavadi’s own childhood mirrors something that happens to her protagonist, Kimiâ. Like Kimiâ, Djavadi was born in Tehran shortly before the Iranian Revolution and can remember when she and her family fled as exiles opposed to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. At one point in the book, Kimiâ and her mother are literally smuggled into their lives on horseback. Kimiâ is the daughter of Sara and journalist-activist Darius Sadr, the man who occupies much of the novel as a loving but aloof figure who has decided that the fight for his country’s soul matters more than the preservation of his family. Kimiâ’s story is partly an attempt to understand Darius, and Darius’s effects on Sara, but also the patriarchal norms that were being upended in a modernizing Iran. Djavadi isn’t content exploring only the disorientation caused by cultural and political revolution; the novel’s transition to Paris brings with it a shift in self-awareness, too. Kimiâ came from an upper-class Iranian family that was something of intellectual royalty, though in France the notion of such stability and assurance begins to seem a silly thing. Disoriental plays with various genres, from magical to social realism, and in its wonderful English translation by Tina Kover, did so at a time when borders between totalitarianism and democracy; Europe and the Middle East; and men and women were being questioned anew. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Scholastique Mukasonga, tr. Jordan Stump, The Barefoot Woman (2019)

Set in Rwanda, before the genocide, The Barefoot Woman defies categorization—it sometimes is described as memoir, others as fiction, but no matter the label it is a tribute of a daughter, Scholastique, to her loving mother, Stefania. The first time Stefania speaks, she says, “When I die, when you see me lying dead before you, you’ll have to cover my body.” These words haunt the rest of the book’s pages, and signify just one of the many recurring instances when Stefania will tell her three daughters stories foreshadowing her death. Though Scholastique is just a young girl and admits she does not always comprehend her mother’s warnings, her mother’s “land of stories” “impregnated the slow drift of [her] reveries.” Bearing in mind the impending genocide while reading, imbues each page with an additional sonorous depth, and as contraries fuel each other, the monstrousness and tragedy of the genocide fortify the mother’s love.

Scholastique Mukasonga reveals, throughout the book, the daily life, customs, and labor that bound mother and daughter and the rest of the Tutsi women to each other and to their land. Each chapter represents a different window into their entwined lives: on “Bread,” on “Sorghum,” on “Beauty and Marriage.” The encroaching violence against Rwanda is felt from the first pages but is anchored by the mother whose worry for her children drives her fastidious efforts to save them; she teaches them the path to the border, she hides food, she listens like a hawk to any sounds of approaching militia. A Finalist for the National Book Award for Translated Literature, The Barefoot Woman is described by Zadie Smith as a “simultaneously a powerful work of witness and memorial, a loving act of reconstruction, and an unflinching reckoning with the Rwandan Civil War.” The memories of childhood, a lost home, a mother who sacrificed herself are the pounding heart of the book, and Mukasonga has produced a work that anyone who might read it will remember. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

***

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Haruki Murakami, tr. Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel, 1Q84 (2011) · Peter Nadas, tr. Imre Goldstein, Parallel Stories (2011) · Alina Bronsky, tr. Tim Mohr, The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine (2011) · Peter Stamm, tr. Michael Hofmann, Seven Years (2011) · Santiago Gamboa, tr. Howard Curtis, Night Prayers (2012) · Laurent Binet, tr. Sam Taylor, HHhH (2012) · Javier Marías, tr. Margaret Jull Costa, The Infatuations (2013) · Herman Koch, tr. Sam Garrett, The Dinner (2013) · Patrick Modiano, tr. Euan Cameron, So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood (2015) · Daniel Galera, tr. Alison Entrekin, Blood Drenched Beard (2015) · Juan Gabriel Vásquez, tr. Anne McLean, Reputations (2016) · Stefan Hertmans, tr. David McKay, War and Turpentine (2016) · Johanna Sinisalo, tr. Lola Rogers, The Core of the Sun (2016) · Yoko Tawada, tr. Susan Bernofsky, Memoirs of a Polar Bear (2016) · Edouard Louis, tr. Michael Lucey, The End of Eddy (2017) · Domenico Starnone, tr. Jhumpa Lahiri, Ties (2017) · Cristina Rivera Garza, tr. Sarah Booker, The Iliac Crest (2017)· Elvira Navarro, tr. Christina MacSweeney, A Working Woman (2017) · Mathias Enard, tr. Charlotte Mandell, Compass (2017) · Pola Oloixarac, tr. Roy Kesey, Savage Theories (2017) · Hideo Yokoyama, tr. Jonathan Lloyd-Davies, Six Four (2017) · Anne Serre, tr. Mark Hutchinson, The Governesses (2018) · Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky, Go, Went, Gone (2018) · Patrick Chamoiseau, tr. Linda Coverdale, Slave Old Man (2018) · Dubravka Ugrešić, tr. Ellen Elias-Bursać and David Williams, Fox (2018) · Leila Slimani, tr. Sam Taylor, The Perfect Nanny (2018) · Roque Larraquy, tr. Heather Cleary, Comemadre (2018) · Jose Revueltas, tr. Amanda Hopkinson and Sophie Hughes, The Hole (2018) · Henne Orstavik, tr. Martin Aitken, Love (2018) · Yukio Mishima, tr. Andrew Clare, The Frolic of the Beasts (2018) · Yoko Tawada, tr. Margaret Mitsutani, The Emissary (2018) · Khaled Khalifa, tr. Leri Price, Death Is Hard Work (2019) · Yoko Ogawa, tr. Stephen Snyder, The Memory Police (2019), Valérie Mréjen, tr. Katie Shireen Assef, Black Forest (2019) · Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (2019) · María Gainza, tr. Thomas Bunstead, Optic Nerve (2019).