A portable typewriter in a carrying case is underneath the seat in front of the bright young man. Sometimes he puts his feet on it. The case is baby blue with a two-inch black leather stripe down the middle. The typewriter inside is an Olivetti Lettera 32, a brand and model that have become the favorites of serious journalists around the world. This is the Louisville Slugger of his profession. Red Smith uses a Lettera 32. Jim Murray. Frank Deford. No doubt Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett, and Shakespeare would have used one, too, if they could have. The bright young man is very proud of his Olivetti Lettera 32.

He is a journalist of sorts, a writer, at least in his own mind, a sportswriter for the Boston Globe, off to cover the first two games of the best-of-seven National Basketball Association finals between the Boston Celtics and the Los Angeles Lakers. He is not afraid to share this fact with whoever might have the fortune to sit next to a sportswriter for the Boston Globe who is off to cover the first two games of the series between the Celtics and the Lakers. (God bless that person.)

The assignment is the biggest the bright young man has had in fifteen months at the newspaper, the biggest of his short career. He is scheduled to cover the whole shebang, a possible two full weeks of athletic bloodletting. Games will be played every other day. Time zones will be flipped and flipped and flipped again. Circadian rhythms will be dismantled and left in late-night coffee shops and airport lounges.

April 23—Boston at Los Angeles

April 25—Boston at Los Angeles

April 27—Los Angeles at Boston

April 29—Los Angeles at Boston

May 1—Boston at Los Angeles (if necessary)

May 3—Los Angeles at Boston (if necessary)

May 5—Boston at Los Angeles (if necessary)

There is the promise of melodrama, suspense, transcontinental electricity inside this schedule. The bright young man can feel it. He has been traveling with the Celtics since the start of these playoffs, has chronicled the team’s successes in Philadelphia and New York to reach the finals. He has latched onto a show that has become much better than it was predicted to be.

The Celtics were supposed to be dead by now. They had finished an embarrassed fourth in the Eastern Division of the NBA with a 48-34 record, nine games behind the first-place Baltimore Bullets, six games behind the third-place New York Knicks. No matter that they were defending champions, had won nine NBA titles in the past ten years, had dominated their sport for an entire decade, the Celtics were supposed to be finished. Done.

The universal judgment was that they were too old. Every year another piece had fallen off the juggernaut, another part that had made the basketball machine function. Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman, Frank Ramsey and K. C. Jones, Tom Heinsohn and celebrated coach Red Auerbach, all future members of the Basketball Hall of Fame, had peeled away, one after another. A host of supporting players like Wayne Embry and Jim Loscutoff, Gene Conley and Willie Naulls, also had departed.

There is the promise of melodrama, suspense, transcontinental electricity inside this schedule. The bright young man can feel it.Sam Jones, master of the jump shot, thirty-five years old, would be the next to depart at the end of the playoffs. A Sam Jones Day already had been held at the end of the regular season at Boston Garden, complete with a proclamation from the City Council, a cake, a dinner, a standing ovation from 13,555 fans, and a gift of the shell of a prefab home that would be built in Silver Spring, Maryland, at his new address. All that was left was for the playoffs to end before he could move.

Bill Russell, the six-foot-ten foundation of all of the success, same age as Jones, also was thinking about retirement. He was in his third year as a player/coach, Auerbach’s replacement. He was in his thirteenth year in a green uniform. As a young coach at thirty-five, he knew the limits of an old player at thirty-five. His body gave him reminders every day. He couldn’t run as fast, couldn’t jump as high. His arthritic knees ached. He had his moments, but, man, he had to spread them out. He had to survive on bursts of energy, rather than the constant flow of high-grade performance that had made him the winningest player in the history of American professional sports.

Bursts were how he had led the team to a tenth championship in 1968, a year ago, lifting the Celtics from a 3-1 hole against the Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Division championship, then to a six-game triumph over the Lakers in the finals. Could he do it again? There were positive signs in the first two playoff series this year, both mild upsets, but not enough to change the minds of the actuarial thinkers in Las Vegas.

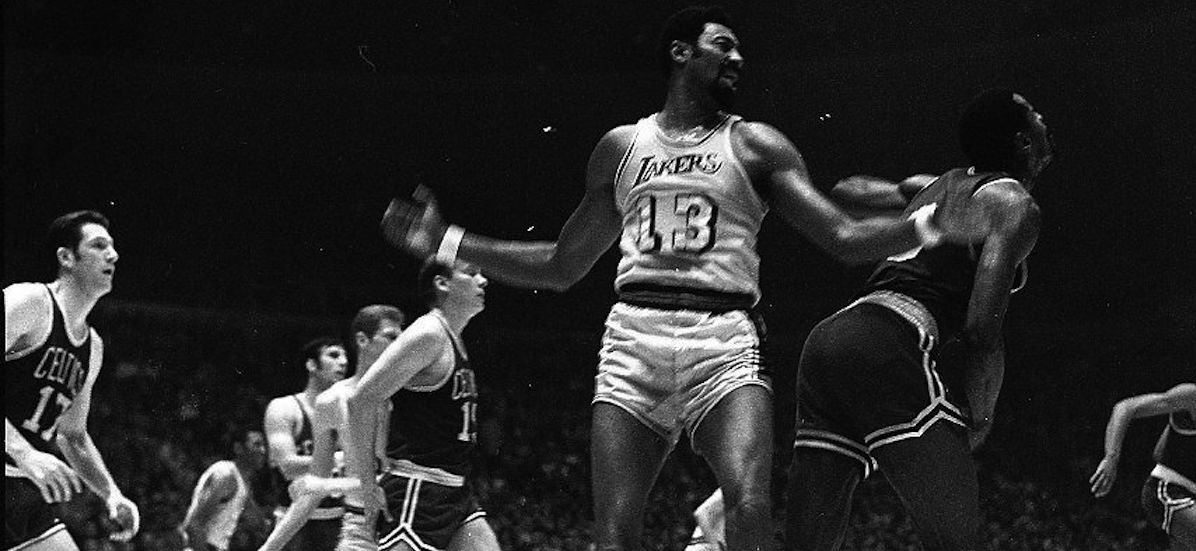

The Lakers are a 9–5 favorite, which pretty much translates to 2–1, large odds for a championship series. This is not a new evaluation. Despite their loss in the finals last year, despite their loss in all six finals they have played against the Celtics in their history, the residents of the Fabulous Forum, 3900 W. Manchester Rd., Inglewood, CA 90305, have been the favorites to win this title since July 9, 1968, three months before the season even started. That was when their owner, Jack Kent Cooke, laid out an astounding $260,000 for the first year of a five-year contract to secure the services of seven-foot-one Wilton Norman Chamberlain. Ranked everywhere except, perhaps, Boston Massachusetts, as the biggest, bestest, most stupendous basketball player in the history of the world, Chamberlain was added to a lineup that included certified superstars Jerry West and Elgin Baylor.

No team like this ever had been assembled in the NBA. It was as if the roster had been cut from the pages of comic books, Superman pasted together with Batman and, oh, the Incredible Hulk or any one of the Avengers in an effort to rid Metropolis of the dark forces that had ruled for so long. The move was unprecedented. There was no such thing as free agency in the NBA or any American professional sport in 1969. Players like Chamberlain simply weren’t available on the open market. They were chained to their employer, indentured, locked into servitude at their latest stop until their owners chose to send them elsewhere.

And yet, here he was.

The word “destiny” seemed appropriate on a bunch of levels for the Lakers and for Wilt. This was the final test before it could be fulfilled.

*

Stories bounce through the young man’s head. Angles. They are there when he wakes up in the morning, there when he goes to sleep. He makes a mental list, changes it, adds or deletes. He conducts imaginary interviews that he hopes will happen. He will be ready for anything. He will make the readers see what he sees, hear what he hears, feel what he feels. The matchups sing to him.

Celtics vs. Lakers

Perpetual Winners vs. Perpetual Losers

Bill Russell vs. Wilt Chamberlain

Fate vs. Jerry West

Sam Jones vs. Age

Age vs. Elgin Baylor

John Havlicek vs. The Four-Minute Mile

Red Auerbach’s Basketball Knowledge vs. Jack Kent Cooke’s Ownership Money

The Athens of America vs. Hollywood

Defense vs. Offense

Running vs. Walking

Teamwork vs. Celebrity

Good vs. Evil (Parochial View)

The Boston Garden vs. The Fabulous Forum

Truth, Justice, and the American Way vs. High Gloss and Big Money

Boston vs. Los Angeles

Yes!

Yes, indeed.

This is an important trip for the bright young man. Excuse, if you can, his self-absorption. Ambition pumps through his body in a daily systolic beat, always there, threatening to explode from his body in inopportune moments. He is young enough to believe that anything can happen. This is a chance to make people notice.

A simple game story will not be sufficient—“The Boston Celtics defeated the Los Angeles Lakers, 110–109, as John Havlicek scored 42 points and Bill Russell pulled down 28 rebounds, blah, blah, blah . . .” The stories of today must do more. They must be different, provocative, but also must read like a page or two from a novel, tell the background of what took place, describe the characters involved, their thoughts and emotions, their answers to the toughest questions. Details. Details. Details. There never can be too many details.

No team like this ever had been assembled in the NBA. It was as if the roster had been cut from the pages of comic books, Superman pasted together with Batman and, oh, the Incredible Hulk.The term that is peddled on the most literate streets in 1969 is “New Journalism.” Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote and Gay Talese are prominent New Journalists in the real world. They not only report the news, they report the colors, the sounds, the brands of cigarettes and automobiles, the contents of the subject’s imagination. The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Wolfe), In Cold Blood (Capote), “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” (Talese). This is revolutionary stuff. Musical. Funky. The dull informative clatter of the Associated Press, say, or the New York Times has been replaced by stories that read like good fiction, stories that talk about thoughts and motivations, reasons, and memories of home and Mama.

The sportswriting business has a different name for the would-be practitioners of this approach to writing. They are called “chipmunks.” Young, mostly under thirty-five, they are irritants to the older generation. Too noisy. Too demanding. Too . . . everything. Jimmy Cannon, the longtime standout columnist in New York, age fifty-eight, grew impatient with these new people and their incessant questions. He said, “They sound like a bunch of chipmunks.” The name stuck. A famous moment came when Ralph Terry, a pitcher for the New York Yankees, won a game in the World Series and said afterward that his wife was home feeding their new baby. “Bottle or breast?” a sportswriter asked. That was a chipmunk question.

The bright young man considers himself part of the revolution. He works for the evening edition of the Globe, so he has later deadlines—pretty much no deadlines at all—and will be able to stay later in the locker rooms, ask his questions, then take time to write his story. Bottle or breast? He will have that story behind the story. He will write it for what he is worth. Breast would be more exciting.

When he first moved to Boston, fifteen months ago, before he was married, he lived in a rooming house on Marlborough Street. Dead asleep one night he was awakened by an alarm and noises in the hall. An orange glow was outside his only window. The Unitarian church on the corner, First Church of Boston, was on fire. The glow was a reflection on a wall of another building.

Half-asleep and panicked, he put on some clothes and grabbed the Lettera 32 in the baby-blue carrying case with the two-inch black stripe down the middle. He went outside and stood on the street. He watched the fire with residents who had grabbed cats and dogs and family photos, antiques, and other treasures. He had grabbed his typewriter.

*

Somewhere in the flight, the beverage cart is replaced by baskets filled with headphones wrapped in plastic. The glamorous stewardesses walk through the plane with the baskets. A movie will be shown. (Is there a charge? Can’t remember.) The fine young man accepts the offer, plugs the power end of the headphones into the armrest, careful to stay away from any possible inferno in the ashtray, inserts the appropriate plugs into his appropriate ears. Small television screens drop from the ceiling in a choreographed entrance, all of them at once. There is a screen at every fourth or fifth row, the entire length of the plane. The movie is Bullitt, starring Steve McQueen.

I watched this movie again on Netflix two nights ago. This was maybe the seventh time I have seen the thing in my lifetime. Holds up well. Steve, if you never saw it or don’t remember, plays Bullitt, of course, the headstrong detective who gets things done, no matter the cost. Jacqueline Bisset is the love interest.

The inescapable fact of this seventh viewing is that I know Steve McQueen will be dead on an operating table in Juarez, Mexico, in twelve more years at the age of fifty. He will try a long-shot operation to combat the many cancerous tumors in his body, but will die of a heart attack. (I looked up the dates and circumstances.) In the movie, Steve still is thirty-eight years old, thirty-eight forever, handsome in that hard-edged way that appeals to both men and women. He takes no shit from anyone. He outwits the bad guys. His face crinkles in all the right places when he smiles. His blue eyes stare into the future that he doesn’t know exists.

The fine young man is entranced. He hasn’t traveled much, certainly not long distances like this, and never has seen a movie on an airplane. The decadence of the experience is wonderful. Smoking. Drinking a Pepsi. (Real Pepsi, not diet.) Stretched out. Watching a movie. Steve McQueen must do this all the time. Fly in a jet. Probably a private jet. Maybe with Jacqueline Bisset at his side. Drink. Smoke. Maybe watch himself on the screen.

Who wouldn’t want to be Steve?

Nobody.

A voice asks everyone to buckle their seat belts, return their seat backs and tray tables to an upright and locked position, make sure all their carry-on luggage is stowed under the seat in front of them or in the overhead bins. The stewardesses prepare for landing.

California!

*

I am going to say the plane flies out over the Pacific Ocean and turns around to land at LAX. I don’t know if this is true, can’t remember, but I’m going to say it does for dramatic purposes. The bright young man looks out the window. (I’m also going to say he has a window seat.) He is spellbound by the sight of the Pacific. There it is. Son of a bitch. He never has seen the Pacific Ocean. He never has been to California. He never has seen a palm tree, except in pictures. There is a lot he never has seen.

In the army, finishing up basic training with the National Guard, he hitchhiked from Fort Leonard Wood to St. Louis once with a guy from New Albany, Indiana. After they drank a lot of beer and went to a baseball game, they visited the famous arch, then went down and spit into the Mississippi River. The guy from New Albany, Indiana, said that a man had to spit into the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Mississippi River to prove that he was a true American male. It sounded like a proper Code of Life. Something important. This will finish the process for the bright young man. Spit into the Pacific.

Will he go to Hollywood, see the names of the stars in the sidewalks? Will he see any stars in real life, doing their shopping or going to the dry cleaners? Will he recognize them? Will he go to a beach? Will he see any surfers? Will he see a Beach Boy? Brian Wilson would be good. Will he see a Dodgers game? Probably not. Will he go to Disneyland? Probably not. Will he go up to Griffith Observatory where James Dean kicked ass in that knife fight in Rebel Without a Cause and captured Natalie Wood’s heart? Rodeo Drive? Venice Beach? Will he ride on a freeway? What’s that like? Will he eat a California orange?

He heads through the terminal confusion toward baggage claim with no problem. All he has to do is follow the heads sticking out of the crowd, the Celtics’ heads, taller than all the other heads. There’s Russell. There’s Tom Sanders. There’s Bailey Howell. The players will lead the way, then stand around, then pick their bags off the luggage carousel, same as the bright young man. They will grab a cab to the Airport Marina Hotel, same as he will. Often the same cab.

There will be no air-conditioned luxury bus. There will be no preferred treatment. Joe DeLauri, the team trainer, also handles the travel arrangements. He will hand out keys at the hotel. All the players except Russell will have a roommate.

The bright young man will follow along. The trainer also will give him a key. His roommates will be those Lucky Strikes and that Lettera 32. The room will be filled with smoke and that clackety-clack noise, a bell at the end of each typewritten line. An ashtray will always need to be emptied. There will be great internal debates about choices of words and phrases, quotes to use and quotes to leave out. Plot lines will evolve. Drama will develop. The characters on the Celtics and Lakers will play their parts, working through a series that will be as memorable as any in NBA history. The bright young man will play his part, clackety-clack, in the room.

He is the twenty-five-year-old me. I am the seventy-seven-year-old him.

He knows nothing about what will happen next. I know pretty much everything.

____________________________________________________

From Tall Men, Short Shorts: The 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt, Rus, Lakers, Celtics, and a Very Young Sports Reporter by Leigh Montville, published by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Leigh Montville.