PRINCE AND APOLLONIA

It’s hard to say exactly whose idea it was, whether it was Yvette’s or mine, but sometime during that summer we began thinking of ourselves as Prince and Apollonia. The whole world, you’ll recall, spent the mid-eighties bathing in Purple Rain. The movie ruled the box office, the album the charts. In truth, we were two sad teenagers stranded in the Atlanta suburbs, a thousand miles away from Prince’s hometown of Minneapolis. But when His Royal Badness told us a locale called Uptown existed in some as yet unidentified mystical realm, we decided we’d rather pretend we were there. Chances are, Uptown had all the amenities our vacuous setting lacked. There was likely even a mall.

And it’s probably fair to say that, had one Prince Rogers Nelson never ascended to the pinnacle of pop culture and commenced his purple reign, Yvette and I never would have exchanged names, much less bodily fluids. Prince acquainted us—in PE class. That spring, I’d been wearing a yellow T-shirt with Prince airbrushed across the front and Rude Boy across the back. Our class was on the asphalt tennis courts in the shadow of the football stadium, and Ms. Monroe was instructing us in the finer points of the backhand grip, when a girl with reddish-blond hair introduced herself first as a Prince fan and later as Yvette. She said she owned every Prince album—and a couple from his notorious secret vault. She said she knew how to decipher that cryptic backward message at the end of “Darling Nikki.” She said her bedroom walls were purple.

Soon we were professing our eternal love for one another.

At first, the effects of this arrangement were minimal, mostly sweet and insubstantial. In the hallways between classes we started exchanging notes mimicking Prince’s shorthand in the album’s liner notes: How r u? Can’t wait 2 c u 2-night. Yvette wore lacy scarves, a pound of mascara, and a single red earring just like Apollonia’s. I hung purple curtains in my bedroom and plastered posters on my walls. I even gave Yvette my class ring, replete with an amethyst stone. Sometimes she’d drop in while I was scooping ice cream at my afterschool gig at Baskin-Robbins, where between customers I’d serenade her with off-key renditions of “Little Red Corvette” and “Delirious.” Which is a hard act to pull off when you’re wearing a pink, orange, and brown striped shirt with butterfly collars and using an ice cream scooper for a microphone.

But as time passed, instead of having actual conversations, we began substituting passages of dialogue from the movie. We’d meet up in the parking lot after school:

Yvette: Hey.

Me: We have to go to your place.

Yvette: What for?

Me: ‘Cause I wanna show you something.

Yvette: We can’t.

Me: Why, is somebody there?

Yvette: Why do you always think there’s somebody else?

Me: Let’s go.

Yvette: Yeah, but we’re not going to my place.

And then instead of climbing aboard my purple motorcycle, we’d take Dad’s Fairlane to the local park, where we’d feed breadcrumbs to the ducks and pretend the murky pond was Lake Minnetonka. Inevitably I’d tell Yvette that, if our relationship were to go any further, she’d have to “pass the initiation,” just like Apollonia had passed Prince’s, by stripping to her skivvies and “purifying yourself in the waters of Lake Minnetonka.” If she took the bait, she’d jump in, just as I halfheartedly hollered, “Wait— ”. Then when she emerged from the water, retching and gasping for breath, I’d of course say, “That ain’t Lake Minnetonka.” Yvette, however, did not follow this part of the script. She had a smaller rack than Apollonia, but a bigger brain.

And there were other complications to our plan, too. Some inconsistencies needed reconciling. For starters, Prince was black; I was white. He stood five-seven in heels; I was six-two in Converse Chucks. He played wicked guitar and 25 other instruments; I had abandoned baritone in eighth grade. Onstage Prince wore underwear closely resembling black panties; I sported tighty-whities. There was also the matter of his blatant sexuality: a minister from a nearby congregation conducted an album burning in his church parking lot and commenced the festivities by dousing a vinyl copy of Prince’s Dirty Mind in lighter fluid. All of which seemed so very cool from a distance as great as ours from Prince.

But these differences became only minor inconveniences when Yvette cued up Purple Rain on her boom box, and we’d lie shoulder-to-shoulder on her basement floor and stare up at the ceiling and vibrate to the sheer palpitating intensity of Prince’s voice when he broke into those screams at the end of “The Beautiful Ones” and demanded his lover make a decision: Do you want him? Or do you want me? Cuz I want you. That kind of bare expression would set our bodies on edge, triggering the release of pheromones or some kind of illicit chemical reaction in our bloodstreams, and we’d curl into each other and be reborn as Prince and Apollonia. The world seemed so small and intimate in those moments, as though all meaning were distilled in the timbre of Prince’s voice. We’d been transported to Uptown.

One night, we were listening to 1999 while news of a tornado warning spread across Atlanta’s metro area. Outside, the alarms sounded in the distance. The wind was gathering in great gusts of fury and the shrubs in the yard were bending under the force and the whole house seemed to be shaking on its foundations. I should’ve headed home an hour ago, when the first reports of bad weather had come through the radio; but now it was too late to risk the roads and all we could do was sit tight and wait it out and hope the house stayed on the ground. So we just settled in and began grooving on that opening title track, and Prince was telling us Everybody’s got a bomb/ We could all die any day. Then he was segueing into the chorus—They say 2000 zero zero party’s over, oops out of time/ So tonight I’m gonna party like it’s 1999. Of course it was still the eighties, and all this chatter about a purple Armageddon amounted to some sketchy forecasting of the future—but the weather outside was indeed ominous, and we were two suburban kids, seventeen years old and absolutely certain that Prince possessed the gift of prophecy.

We believed him.

* * * *

Apparently my father was sensing the inevitable. A Southern Baptist deacon, Dad believed sex required a ring, a preacher, and a marriage license—and even this holy trinity was subject to the laws of propriety.

One night, while we watched a Braves game, Dad casually initiated a conversation. Sometime during the middle innings, he said, “You and that girl have been spending a lot of time together.” He kept his eyes glued to the TV screen. As though he were just talking out loud to himself.

Throughout my adolescence, there had been no bird-n-bees talk in our house, no rote summary of the biology, and something in Dad’s tone made it clear that this conversation would be as close as we would ever come to one. To this point, females had merited no discourse whatsoever between us. Dad was aware, I’m sure, that my voice had deepened some time ago and my body changed, and therefore girls were high on my list of priorities. But sixty-hour workweeks at the Post Office probably had become a blessing of sorts for him, a convenient excuse for not having to delve too deeply into his son’s messy emotional life.

“What’s her name again?” he asked.

“Yvette.”

We both stared at the screen. We worked hard to convince ourselves what was going down here. We were not having a conversation about females, much less about sex. We were watching a baseball game.

Then, after a long pause, a series of pitches and a couple of batters, came this: “You know a woman’s body is a temple of the Holy Spirit, right?” he said.

I was vaguely aware that he was making a reference to scripture, and that he was invoking what my English teacher called a metaphor, though my blue-collared father wouldn’t have known to call it that. This was no simile; he was saying a woman’s body is a temple of the Holy Spirit. But I wasn’t sure what he ultimately was getting at—whether he was telling me not to carry a scroll into the temple; or to make sure the scroll was clean if I did enter; or to be sure to wrap the scroll in a sacred cover. It was all a mystery.

I waited for further clarification.

None was forthcoming.

But by this time, thankfully, the question had been sitting there long enough for both of us to reasonably think we could forget it had been asked in the first place. Just in case, though, I let it linger a little longer. I pretended to watch the action until eventually, that’s again all we were doing—watching a baseball game.

The next pitch was a slider, low and inside. But with his next offering, a 2-2 pitch, the southpaw tried to sneak a fastball by Dale Murphy, who lined it into left field for a solid base hit.

“Murph could be a decent ballplayer,” Dad said, “if he didn’t strike out so much.”

* * * *

During my epoch of my life, I spent all of my time at school, Yvette’s, or the Baskin-Robbins where I worked.

Among my scooping colleagues, a kid named Destry was what our manager called a “provisional employee.” Destry was fifteen. His mother drove him to work. Desperate for employees, the manager had hired Destry on a trial basis. If he successfully proved himself he would be hired at full minimum wage: $3.35 per hour. But if the manager had actually paid any attention to Destry, he would have known that his newest worker should be terminated—immediately. Destry’s uniform, including his 31 visor, constantly reeked of weed. Anytime a Van Halen song came on the radio—and let’s remind ourselves, it’s the mid-eighties, so when a Prince song isn’t on the radio, a Van Halen song most certainly is—Destry amped up the volume and refused to help the next impatient customer until he’d finished ripping through Eddie Van Halen’s solo on his air guitar. Under his breath he frequently mumbled crude and offensive comments about customers, especially old people, whom he universally referred to as “Q-tips.” He flirted shamelessly with college coeds who dropped in for low fat yogurt, savoring the skin-to-skin contact when he handed them their change, gaping slack-jawed at their backsides as they exited the store. To summarize: Destry lived with the sincere conviction that at every waking moment he was one second away from getting laid.

Which is exactly what he would have you believe. Destry regularly entertained us with tales of his bawdy escapades. He was dead-set on cataloguing his conquests for us, documenting every in and out of his illustrious career as a lover. If dismal weather outside meant no customers inside, we’d sit around the tubs of Mint Chocolate Chip and listen to Destry weave salacious fantasies. According to Destry, his mom, who was single and worked nights, would push a ten into his hand and tell him to order a pizza as she headed out the door for an eight-hour shift. Immediately he’d be on the phone, importing a veritable harem of heavy metal chicks into his room. He’d recount for us how, under the watchful gaze of Ozzy Osbourne peering down from the poster above his bed, these girls would fulfill their sole desire in life: to sate Destry’s insatiable sexual appetite.

It was all cock and jive, of course. Or most of it anyway. The challenge was figuring out which was which—until finally you gave up and willingly suspended your disbelief. We didn’t care. Destry made time go faster, God bless him. On a slow night, we’d shake our heads at the realization that we’d just killed a solid hour sitting around listening to Destry make himself out to be a Headbanging Hero at the peak of his carnal powers.

Destry seemed to relish Yvette’s visits to the store. He did not attempt to hide his lust. “Damn,” he’d say when he saw her crossing the parking lot toward the store. “Lookit that shit.” Once she was inside, he’d intercept her, offering a free scoop of Rainbow Sherbet, her favorite, and noting how good her hair looked. With subtle grace, Yvette became practiced at rejecting his overtures, and somehow I took his comments more as a compliment than an affront.

But one slow afternoon, after ogling her departure, Destry turned toward me with that sly and wicked grin and asked, “How does she like it, bro?”

I proceeded to start wiping down the counter, even though it was already clean. Which of course broke the tacit code between boys that all sexual activity was subject to public discourse. I was keenly aware I was violating an agreement, veritable and longstanding.

Destry eyes grew wide and incredulous. “You mean to tell me you ain’t hitting that?”

“I didn’t say that,” I told him. “I didn’t say anything.”

“You ain’t getting any,” he declared.

“You don’t know what I’m getting.”

“Else you’d be telling everybody,” he said.

“I wouldn’t be telling you,” I offered.

He shook his head mournfully. “Man, if you ain’t getting that poontang, you must be homo.”

“I’m not homo.”

“Serious queer bait.” He tsked his tongue. “What a waste.”

“Screw you.”

I started drifting away, toward the supply room in the back—anywhere to get some distance. But Destry trailed me, his voice actually veering toward sympathy. There was, dare I say, compassion in his tone. Something that, to my evangelical ears, sounded curiously like grace. “Just get you some, bro,” he said. “Ain’t no reason to be scared of it.” He was patting me on the shoulder now. “Do it,” he advised. “And if you like it, do it again.”

I understood the dangers of giving ear to such an imposter, a boy who had gotten so lost in the maze of his own imagination that even he wasn’t sure when a Motley Crue song ended and his real life began. But almost immediately I was ducking inside the walk-in freezer in the supply room to contemplate Destry’s statement. The frigid air blasting from the fan served to clear my head, heighten my senses. Surrounded by a hundred tubs of ice cream, I repeated Destry’s advice, trying it out on my tongue—Do it, I told myself, and if you like it, do it again—the visible clouds of frost giving the words concreteness. Saying the words aloud, seeing them form into puffy shapes, made them tangible. Made them real. In their unadorned simplicity, they struck me as the most profound sexual advice I’d ever received.

When I exited the freezer, I had more than a new life philosophy.

I had a plan.

* * * *

About the implementation of that plan I remember very little. The logistics seemed to involve one of Yvette’s mom’s fiancée’s weekend gigs at an Italian restaurant—where he and two other fortysomething men with receding hairlines formed a cocktail jazz trio that sounded like elevator music in a retirement home. The restaurant was in Rome, Georgia, a hundred miles away. Yvette and I begged off the assignment, lamenting homework, tests, etcetera. Those teachers are real slave drivers! we complained with straight faces. I didn’t possess the kind of transcript that would make these excuses ring with any authenticity, but Yvette was in fact a stellar student, and sounded convincing when she offered her account of the intellectual evening that lay before us.

After the fiancée’s four-door hatchback disappeared from view, we probably spent some time watching television, scrolling through the channels, checking out the latest videos on MTV, assuring ourselves that they hadn’t forgot something and really had vacated the premises for the entire evening. We probably availed ourselves of whatever was in the fridge or the cupboards. We might even have indulged in one last review session by watching a scene or two of Purple Rain in search of final reminders.

But at some point we climbed the stairs. There was ceremony, sure—too much of it, in fact. We knew our roles. The spastic, incompetent groping of teenagers was what should have been going on here, but we were thinking too much for that. If the sexperts on Phil Donahue were right when they claimed sex is as much mental as physical, then we were performing quantum physics here. In our attempt at making it special, we began kissing as though obeying meticulous stage directions. There was something very Days of Our Lives about removing our clothes. Yvette shut the blinds and slid a cassette into her boom box. She cued up “When Doves Cry.” The song, I knew, was five minutes and fifty-two seconds. I hoped I would last that long.

Nothing particularly remarkable happened. There were the requisite whispers that we’d waited so long for this moment. The mechanics to figure out, too, the real life application of the details. All the particulars I still vaguely recollected from eighth grade Sex Ed. But we managed. Biology did its part.

I recall the smell of shampoo in Yvette’s hair. Her hands on my back. Maybe the play of shadows on those lavender walls. The rest seems to have been lost in the fog of memory.

Except this: I do know that what happened in that three-bedroom contemporary on that spring night in the eighties in no way resembled what we’d seen Prince and Apollonia do on the Midwestern prairie.

But it wouldn’t be until after I kissed Yvette goodnight and drove home that I started to see the significance of this turn of events. By the time I nudged open the front door of our brown brick on King Arthur Drive and killed the porch light Mom had kept glowing for me, already I was thinking of tonight as a kind of mystical encounter. Inside, the house was silent. Mom and Dad had gone to bed. The fact I was the only one awake in the house, and maybe in the entire world, felt like it mattered. I crept through the kitchen and went into the bathroom and sidled up to the mirror, where I stared at my reflection. I expected to find a stranger there, a new being awaiting proper introduction. I searched my features for signs that I looked different; that somehow people might be able to simply glimpse me and recognize my journey into foreign lands.

But the kid in that mirror looked much the same as he had last time he viewed himself. He seemed, between then and now, to have found no secret knowledge. In a few short months he’d be heading to college—to a school that admitted anyone with a pulse and a high school diploma—and by all appearances he’d be just another kid from suburbia despite what happened tonight. But he was seventeen, and subject to all manner of reinvention from moment to moment, and he was accustomed to assuming a new swagger and pose. So he threw back his shoulders and set his jaw, and waited.

Tomorrow was Sunday, a new day and a new Sabbath, which seemed for all the world right and true. This Baptist boy could vouch for the gospel in his father’s words. After all, he had now been inside the temple. He’d felt the Holy Spirit.

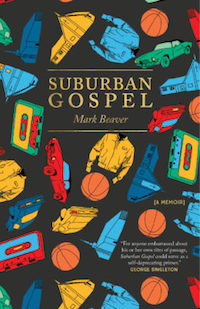

From Suburban Gospel by Mark Beaver. Used with permission of Hub City Press. Copyright © 2016 by Mark Beaver.