This talk is going to be partly at least about children’s literature, or so it says in the program. I should say at the outset that I’m not going to treat the subject in an academic way, even if I could; I find it hard to think about anything for very long, or at all deeply, unless I can get some practical grasp of it. My qualifications for saying anything about books that children read are strictly limited to the fact that I write them. So these reflections are those of someone who makes up stories and thinks about how he does it, rather than those of a scholar who has studied the subject from an academic point of view.

I thought I should begin by trying to say what children’s literature is; but that’s not as easy as it seems. We think we know what it is—there are books about it, you can be a professor of it—but it still seems to me rather a slippery term. It’s not quite like any other category of literature.

For example, if we go into a large bookshop we find many different ways of dividing up the stock. We find books separated by genre, for example horror, crime, science fiction; but children’s books—children’s literature—isn’t a genre in that sense.

However, we also find shelves labelled women’s literature, black literature, gay and lesbian literature. Is children’s literature like that?

Surely there isn’t a complete and unbridgeable gap between them, the children, and us, the grown-ups; or between their books and ours.No, it isn’t like that either, because books of those kinds are written by members of the named groups as well as being about them and for them. After all, those categories, those bookshelf labels, came into being because people felt they needed a voice, not just an ear. They didn’t say, “Write more stuff for us!” They said, “We are writing, and we want to be read.”

But children’s literature isn’t produced by children. It’s written, edited, designed, published, printed, marketed, publicized, sold, reviewed, read, taught at every level from nursery school to post-graduate, and very often bought by adults. A novel written by a child is a very rare thing. Whereas we accept the idea of the child prodigy in the fields of music or chess or mathematics, those activities depend on abstract pattern-recognition more than on the sort of stuff that novels are made of, namely experience of life. A ten-year-old child writing something like A Dance to the Music of Time, say, or Pride and Prejudice, or Tom’s Midnight Garden, would be not a prodigy but a monster.

I’m talking about novels, not poetry: poems, at least to the extent to which they are patterns themselves, seem to be more within the reach of a young mind, and we’ve seen remarkable poems produced by young children under the guidance of good teachers such as Jill Pirrie (author of On Common Ground: A Programme for Teaching Poetry, Hodder, 1987)—though when I was teaching young children I was occasionally reminded of that observation by the pre-Socratic philosopher Ion of Chios: “Luck,” he said, “which is very different from art, sometimes produces things which are like it.” I’m perpetually conscious of the part that luck plays in my own work; it would be odd if it played no part in the work of others. We need to give children plenty of opportunity to be lucky.

So children’s literature isn’t like women’s literature or black literature; but there’s another difference as well. Membership in those other groups I mentioned is presumably a permanent condition: I have always been male, and white, and heterosexual, and while we can never be completely sure what’ll happen tomorrow, I’m fairly safe in saying that I always will be. But I was once a child, and so were all the other adults who produce children’s literature; and those who read it—the children—will one day be adults. So surely there isn’t a complete and unbridgeable gap between them, the children, and us, the grown-ups; or between their books and ours. There must be some sort of continuity here; surely we should all be interested in books for every age, since our experience includes them all.

Or so you’d think. But it doesn’t seem to work like that. To look at the reception of children’s literature today, you’d think that it was a separate thing entirely, almost a separate country, because there are important people like literary editors and critics, who decide what should go where, and why. People who act like guards on an important frontier, and who walk up and down very importantly carrying their lists and inspecting papers and sorting things out. You go there—you stay here. There was an example recently in the Times Literary Supplement. An eminent critic and poet was reviewing a novel that appeared on its publisher’s adult list. The critic called it “too simple by a mile,” placed much of it on the abysmal level of Kipling’s Thy Servant a Dog, said, “The glossary of Australian slang terms is over-literal and out-of-date,” and laid into it heartily for being sentimental.

However, he added, “as a children’s book, it might make its mark.”

So children’s books, apparently, are like bad books for grown-ups. If you write a book that isn’t very good, we’ll put it over there, among the stuff that children read.

Critics must think that we grow up by moving along a sort of timeline, like a monkey climbing a stick.That’s not a view that’s unique to this country, and nor is it confined to the books themselves. Their authors are not very good either. A year or two ago I saw a piece by Robert Stone in the New York Review of Books. He was writing about Philip Roth’s latest novel. Stone opened by praising Roth for his great achievements in the past 30 years, the authority of his voice, his energy, his manic but modulated virtuosity, and so forth. Then he went on to say that Roth was—these are his words—“an author so serious he makes most of his contemporaries seem like children’s writers.”

Well, that put me in my place. You can imagine how embarrassed I felt at not being serious, and having a voice with no authority, not to mention a virtuosity that was sober and unmodulated.

The model of growth that seems to lie behind that attitude—the idea that such critics have of what it’s like to grow up—must be a linear one; they must think that we grow up by moving along a sort of timeline, like a monkey climbing a stick. It makes more sense to me to think of the movement from childhood to adulthood not as a movement along but as a movement outwards, to include more things. C. S. Lewis, who when he wasn’t writing novels had some very sensible things to say about books and reading, made the same point when he said in his essay “On Three Ways of Writing for Children”: “I now like hock, which I am sure I should not have liked as a child. But I still like lemon-squash. I call this growth or development because I have been enriched: where I formerly had only one pleasure, I now have two.”

But the guards on the border won’t have any of that. They are very fierce and stern. They strut up and down with a fine contempt, curling their lips and consulting their clipboards and snapping out orders. They’ve got a lot to do, because at the moment this is an area of great international tension. These days a lot of adults are talking about children’s books. Sometimes they do so in order to deplore the fact that so many other adults are reading them, and are obviously becoming infantilized, because of course children’s books—I quote from a recent article in The Independent—“cannot hope to come close to truths about moral, sexual, social or political” matters. Whereas in even the “flimsiest of science fiction or the nastiest of horror stories . . . there is an understanding of complex human psychologies,” “there is no such psychological understanding in children’s novels,” and furthermore “there are nice clean white lines painted between the good guys and the evil ones” (wrote Jonathan Myerson in The Independent, 14 November 2001).

Consequently any adult reading such stuff is running away from reality, and should feel profoundly ashamed.

In the same week, however, we had a well-known journalist and social commentator saying that children’s books are worth reading, because: “People are desperate for stories . . . Yet in our postmodern, deconstructed, too-clever-by-half culture, narrative is despised and a cracking read is as hard to find as a moth in the dark” (Melanie Phillips, Sunday Times, 11 November 2001).

So there’s a lot of tension along this border—a lot of pride and suspicion and harsh words and dangerous incidents. It might flare up at any minute, we feel.

But when we step away from the border post, when we go round the back of the guards and look about us, we see something rather odd. The guards have entirely failed to notice that all around them people are walking happily across this border in both directions. You’d think there wasn’t a border there at all. Adults are happily reading children’s books; and what’s more, children are reading adults’ books. A thirteen-year-old boy of my acquaintance was a passionate reader of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled; and only the other day I spoke to some children in the public library in Oxford, none of them older than thirteen, and found that they were reading, among other things, Dorothy L. Sayers, Agatha Christie, Ruth Rendell, Ian Rankin, Stephen King, David Eddings, Helen Fielding—much of it genre fiction, to be sure, but all of it firmly on the adult side of the border.

And I well remember my own childhood reading consisting among other things of Aldous Huxley and Lawrence Durrell as well as Superman and Batman, Arthur Ransome and Tove Jansson at the same time as Joseph Conrad and P. G. Wodehouse, Captain Pugwash overlapping with James Bond—a whole mixture of things, both apparently grown-up and apparently not. Furthermore, a book that made a great impression on me and my young schoolfriends was Lady Chatterley’s Lover. So highly did we think of its qualities that we used to pass it around from hand to hand; in fact, like many copies of that book, it used to fall open at the passages most keenly admired.

Now it’s quite common to criticize this kind of cross-border reading on the grounds that it’s reading for the wrong reasons. Adults today are reading Harry Potter, apparently, in order to be in the fashion, or to retreat into a state of childish irresponsibility; the teacher who confiscated our copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover did so because he thought it wasn’t the literature we were after, but the sociology. At least, I think that’s what he said; he said it in Welsh.

I don’t believe for a second in criticizing anyone for reading for the wrong reasons.Reading for the wrong reasons is something that the guards on the border never do, but which other people do all the time, unless they’re supervised. Well, my view about that is that even if there are right and wrong reasons for reading, I don’t know what they are when I’m doing it, never mind anybody else. What’s more, it’s none of my business, and to make it still harder, everything is more complicated than we think. An ignoble reason for doing something can turn into a worthy one; as well as being intrigued by the sociology that was going on in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, I do remember being fascinated by the way Lawrence put words together.

This sort of mixing-up happens all the time, and in other fields as well as literature. One minute we’re admiring the way Degas puts his pastel marks on the paper, the next we’re wondering what it might be like to kiss the model. But then we notice something intriguing in the diagonals of the composition, and that sets us thinking about the Japanese print in the painting by Van Gogh on the other wall of the gallery, and while we’re thinking about Japanese art we remember that very sociological woodblock print involving the fisherman’s wife and the octopus; and that reminds us that it’s time for lunch. But on the way out, we look again at Degas, and think that his way with pastel really is exquisite. He puts this color against that one, and something quite different happens. Could I do that with words? we think. How would it work?

And so on. Which are the wrong reasons there, and which are the right ones? They’re all mixed up together inextricably. And no one else can possibly know whether to condemn us for the ignoble, or praise us for the worthy. So I don’t believe for a second in criticizing anyone for reading for the wrong reasons. We’re much better off minding our own business.

In a similar way, I don’t think it makes any sense for someone else to decide who should read this book or that. How can they possibly know? Much better not to decide at all, and just let things happen. One of the questions I’m addressing this evening is that of what children’s and adult literature have got in common: one thing they have in common, plainly, is that both literatures, whatever they are, are read by both groups, whatever they are. But as I began by saying, I’m thinking in a practical way of what will help me write; and one thing that helps me do that is the vision of a marketplace.

I like to imagine the literary marketplace as if it were precisely that, a place where a market is being held, a busy open space with a lot of people buying and selling, and eating and drinking, and stopping for a gossip, and walking through on their way to somewhere else, or just running up and down and playing; and in this corner there’s someone playing the fiddle, and over there is a juggler, and here’s a storyteller on his square of carpet with his hat in front of him, telling a story.

And some people have gathered to listen.

They’ve got heavy shopping bags in their hands, and they probably can’t stay for long, but still, they’re intrigued, they want to know what’s going to happen next, so they stay a minute more, and then another, just to see how it turns out; and there’s an old man leaning on a stick, and here’s a child sucking a lollipop, and they’re both listening hard; faces looking over shoulders or peering between taller bodies, pressed together, crammed close, all listening. And some other people go past and listen for a moment and decide it’s not for them, so they go on somewhere else; and others walk past entirely oblivious, chatting together without noticing the story at all; and once in a while someone who has to leave and catch a bus sees a friend and says, “There’s a good story going on over there, you ought to go and listen.”

And when the story’s over, some coins fall in the hat. The storyteller catches his breath and stretches his legs and then sits down to start another tale.

That’s a picture of storytelling in an imaginary state of nature, so to speak: one storyteller, one tale, one audience, and no borders between anyone or anything. It’s imaginary, because for one thing I’m deliberately ignoring the differences which I know exist between writing and telling, between reading a story and listening to it; but this is an abstraction, and I’m ignoring those differences for a particular purpose, which I’ll come to in a minute.

In the real world, the literary marketplace is nowhere near so simple as the one I’ve just described. We haven’t got just the storyteller and the audience any more; there are other people in the business too.

For example, there are some who go to the storyteller and say, “I happen to have the lease of that prime site under the trees, next to the fountain, where a lot of people pass by. I can guarantee you a big audience if you split the money in the hat with me—as a matter of fact, I can offer you an advance on your takings.”

There are others who go to the storyteller and say, “That’s all very well, but what’s the split they’re asking for? What? Let me handle the deal and I’ll guarantee you a better return than that. I’ll only take ten per cent.”

There are some who say to the storyteller, “Look, you’re attracting a big crowd, but half of them are leaving without paying. Let me sell tickets—that way we can be sure of making a decent amount. Did I say we? I meant you, of course, but I’ll need to cover my expenses.” And then there are those who, noticing the number of people looking for a good story and the number of storytellers in business, set up an advisory service. “I’ve listened to all these storytellers,” they say, “and for a very small consideration I can point out the good ones. There’s a cracking yarn going on just now by the flower stall—bright young talent, well worth a visit. As for old so-and-so next to the bus stop, he’s been recycling the same stuff for days now, you’ve heard it all before—frankly, I wouldn’t bother.”

Segregation always shuts out more than it lets in.And in recent years, storytellers have had a new sort of service offered to them. “It’s no good just telling your story these days—you need to attract attention to yourself. Pay me, and I can guarantee to get you talked about. I can’t buy your story a good report from the advisory service, but I can promise lots of interest in you. By the way, you need to get your hair cut—and wear something blue tomorrow.”

Now most of those other people who come between the storyteller and the audience do so for the best of reasons, and few of us in the real world would want to be without the services that publishers and booksellers and literary agents and critics provide. I’m glad they’re there. But among the other intermediaries in this imaginary marketplace are the security guards. They are another branch of the same service that watches the border. They’re interested in the audience more than the stories. They make it their business to say, “This story is only for women.” Or, “This story is intended especially for very clever people.” Or, “The only people who will enjoy this story are those under ten.”

They sort out the audience, and chivvy some this way, some that way, and if they could, they’d make them stand in lines and keep quiet. Some of them even want to give the audience a test on the story afterwards—but I shall say no more about our current educational system.

The result is that instead of that audience I described earlier, all mixed up together, old and young, men and women, educated and not educated, black and white, rich and poor, busy and leisured—instead of that democratic mix, we have segregation: segregation by sex, by sexual preference, by ethnicity, by education, by economic circumstances, and above all, segregation by age.

But, as I pointed out, the trouble is that no one can tell what is going on in a mind that’s reading or listening to a story; no one can know whether we’re reading for the right reasons or the wrong reasons, or what’s right and what’s wrong anyway; no one can tell who’s ready and who isn’t, who’s clever and who isn’t, who’ll like it and who won’t.

Not only that; do we really believe that men have nothing to learn from stories by and about women? That white people already know all they need to know about the experience of black people? Segregation always shuts out more than it lets in. When we say, “This book is for such-and-such a group,” what we seem to be saying, what we’re heard as saying, is: “This book is not for anyone else.” It would be nice to think that normal human curiosity would let us open our minds to experience from every quarter, to listen to every storyteller in the marketplace. It would be nice too, occasionally, to read a review of an adult book that said, “This book is so interesting, and so clearly and beautifully written, that children would enjoy it as well.”

But that doesn’t seem likely in the near future.

Can we ever have a state of things free from labeling and segregating, though? And if we can’t, what’s the use of imagining this democratic open-to-all marketplace which doesn’t really exist?

Well, my reason for thinking about it is strictly practical. Storytellers can do exactly what they like. Those who want to speak only to adults may do so with perfect freedom, and I shall be there in the audience. Those who want to speak only to children may do so too, and if what they say has nothing to interest me, I’ll pass on and leave them to it.

But as a storyteller myself, and one who depends on the contents of the hat to pay the mortgage and buy the groceries and save up for my old age, I don’t want my audience to be selected for me; I want it to be as large as possible. I want everyone to be able to listen. The larger the crowd, the more goes in the hat.

Besides, it’s more interesting. The work you do to keep a mixed audience listening is technically intriguing.

So, for purely practical reasons, I turn to this imaginary and abstract vision because I find that it brings about, in the field of storytelling, something not unlike the “original position” in John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice. According to Rawls, the “original position” is the state in which we are to imagine ourselves behind a veil of ignorance, without knowing what position in society we actually occupy. In this original position we can work out what principles should govern a society that would be just and fair to all, given that we might find ourselves anywhere in it. In real life, we know what position we occupy, and we’re influenced by all sorts of considerations— not only selfish ones—to favor that position over others; when we’re distracted by the knowledge of where we really are, it becomes much harder to see the way to bring about justice for all.

Similarly with the storyteller in the marketplace. I find that there are certain practical ways in which this “original position” idea—the picture of the storyteller and the mixed audience, whose attention I have to keep, but whose reasons for listening, right or wrong, are none of my business—does help me to think about what I’m doing when I tell a story, and what a story is, and how I could tell it most effectively.

Your postmodernist doubts about narrative and fictionality are never going to be as interesting as the people and the events in the story you’re telling.For example: if you’re going to keep people listening, you need to know your story very well. You need to think about it and go over it and clarify it so that you know the line of the story as well as you know the journey from your front door to the bus stop. By “the line of the story” I mean the connection between this event and that one. The world in which Little Red Riding Hood meets the wolf contains all sorts of events and facts and histories, and we could make them up if we had time, but the story we know as “Little Red Riding Hood” ruthlessly ignores most of them. It goes in a line from one event to the next, and in a good telling those events will be in the most effective order and follow swiftly and cleanly one after another; everything that’s important will be there, and everything that’s irrelevant will be left out.

The same, of course, is true of any great novel. Given the events that take place in and around the town of Middlemarch, the book that’s named after it tells their story about as well as it could be told. It does many other things besides, but that is one thing it does do.

The advantage of thinking yourself into the original position here is that it helps you concentrate on getting the story as clear as possible. Without taking anything into consideration but the audience-that-includes-children-but-doesn’t-entirely-consist-of-them, you can work at the story like a craftsman, calmly and quietly going about the task without imposing your own concerns or your own personality on it. If you’re going to keep them all listening, you have to subdue everything that you think makes you interesting.

As a matter of fact, you the intelligent, well-read, educated storyteller and your postmodernist doubts about narrative and fictionality, your anguish about jouissance, are never going to be as interesting, to this mixed audience, as the people and the events in the story you’re telling. Realizing this is a great help when it comes to overcoming the tormenting self-consciousness that many writers of stories feel and have felt for a century now, and which I fully understand, and which I used to share: because when you tell a story to an audience that includes children, you actually become invisible. You don’t matter any more. You can be impersonal about it.

This impersonality brings me to the second consideration, which is the matter of style. How do you put the words together? What kind of voice are you hearing in your head? What kind of voice does the story want?

This is partly a matter of taste. But a limpid clarity is a great virtue. If you get that right, the story you tell will not seem to anyone as if it’s intended for someone else. No one is shut out. There are no special codes you have to master before you can follow what’s going on. Of course, this sort of thing has been said many times before; W. H. Auden and George Orwell both compared good prose to a clear windowpane: something we look through, not at.

Which naturally brings me to the next question: what are you inviting your audience to look at, through the window of your telling? What are you showing them?

If you want your mixed crowd to be interested, you have to make up interesting things. Here’s an interesting scene. In a little inn, a country doctor is talking calmly over a pipe and a glass, and in another corner of the parlor, a drunken sea-captain is singing loudly.

The captain . . . at last flapped his hand upon the table in a way we all knew to mean—silence. The voices stopped at once, all but Dr. Livesey’s; he went on as before, speaking clear and kind, and drawing briskly at his pipe between every word or two. The captain glared at him for a while, flapped his hand again, glared still harder, and at last broke out with a villainous, low oath: “Silence, there; between decks!”

“Were you addressing me, sir?” says the doctor; and when the ruffian had told him, with another oath, that this was so,

“I have only one thing to say to you, sir,” replies the doctor, “that if you keep on drinking rum, the world will soon be rid of a very dirty scoundrel!”

The old fellow’s fury was awful. He sprang to his feet, drew and opened a sailor’s clasp-knife, and, balancing it open on the palm of his hand, threatened to pin the doctor to the wall.

The doctor never so much as moved. He spoke to him, as before, over his shoulder, and in the same tone of voice; rather high, so that all the room might hear, but perfectly calm and steady: “If you do not put that knife this instant in your pocket, I promise, upon my honor, you shall hang at next assizes.”

Then followed a battle of looks between them; but the captain soon knuckled under, put up his weapon, and resumed his seat, grumbling like a beaten dog.

“And now, sir,” continued the doctor, “since I now know there’s such a fellow in my district, you may count I’ll have an eye upon you day and night. I’m not a doctor only; I’m a magistrate; and if I catch a breath of complaint against you, if it’s only for a piece of incivility like tonight’s, I’ll take effectual means to have you hunted down and routed out of this. Let that suffice.”

Soon after Dr. Livesey’s horse came to the door, and he rode away; but the captain held his peace that evening, and for many evenings to come.

Treasure Island, of course. Another scene that’s interesting in a similar way is the return of Odysseus to Ithaca, stringing the great bow that none of the suitors can manage.

So they mocked, but Odysseus, mastermind in action, once he’d handled the great bow and scanned every inch, then, like an expert singer skilled at lyre and song—who strains a string to a new peg with ease, making the pliant sheep-gut fast at either end so with his virtuoso ease Odysseus strung his mighty bow.

Quickly his right hand plucked the string to test its pitch and under his touch it sang out clear and sharp as a swallow’s cry.

–(Homer’s The Odyssey, from book 21: 451–458, translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin Classics)

I was once telling that story to my five-year-old son, and he was so tense and excited that at the point when the string sang out clear and sharp as a swallow’s cry, he bit clean through the glass he was drinking from. You can hardly get more interested than that.

Scenes like these never fail, because they involve danger and tension and courage and resolution, circumstances and qualities which listeners or readers of every age respond to. Not every story has to involve high adventure, by any means; but no successful storyteller is afraid of the obvious—of conflict and resolution, faithfulness and treachery, passion and fulfillment. If your narrative shies away from a situation because you think it will seem hackneyed, if you wince fastidiously and refuse to follow your characters where they want to go, on the grounds that you don’t want to be mistaken for the other writers, less good than you are, who have gone there before, then the audience will go away and find another storyteller with more vigor and less self-importance.

Another very important thing we can discover in this original position is that of stance—not quite the same as voice, not quite the same as point of view; it’s a mixture of where the camera is, so to speak, and where the sympathy lies. I recently re-read some of Richmal Crompton’s William stories, and found her particular stance more interesting than I remembered. The story in which William and the Outlaws first encounter Violet Elizabeth Bott ends with them pretending to rescue her and being rewarded, but the money is small consolation for the shame they’ve had to endure at being manipulated by her all morning.

They tramped homewards by the road.

“Well, it’s turned out all right,” said Ginger lugubriously, but fingering the ten-shilling note in his pocket, “but it might not have. ’Cept for the money it jolly well spoilt the morning.”

“Girls always do,” said William. “I’m not going to have anything to do with any ole girl ever again.”

“’S all very well sayin’ that,” said Douglas who had been deeply impressed that morning by the inevitableness and deadly persistence of the sex, “’s all very well saying that. It’s them what has to do with you.”

“An’ I’m never going to marry any ole girl,” said William.

“’S all very well sayin’ that,” said Douglas again gloomily, “but some ole girl’ll probably marry you.”

There’s a very subtle and fluid mixture here of sympathy and satire, of affection and mockery, of cool knowledge and the memory of what it is not to have it; it’s a matter of being with the characters but not entirely of them, and it’s a stance that works very well with this mixed audience.

Courtesy comes into it too: an attitude to the audience that doesn’t assume either that they’re simple and need to have things made easy for them, or that, since only clever people read books, you can make jokes about how dull everyone else is. A recent writer of books that children read who embodied that kind of courtesy perfectly was Henrietta Branford, whose early death robbed us of someone who, in my view, might have become the best of us all.

Meanings are for the reader to find, not for the storyteller to impose.The last point I want to make is that in a good telling—the sort one tries to emulate, or bring off oneself—the events are not interpreted, but simply related. “Events themselves,” as Isaac Bashevis Singer said, “are wiser than any commentary on them.” Don’t tell the audience what your story means. Given that no one knows what’s going on in someone else’s head, you can’t possibly tell them what it means in any case.

Meanings are for the reader to find, not for the storyteller to impose. The sort of story we all hope we can write is one that will resonate like a musical note with all kinds of overtones and harmonics, some of which will be heard more clearly by this person’s ear, others by that one’s; and some of which may not be heard at all by the storyteller. What’s more, as the listeners grow older, so some of the overtones will fade while others become more clearly audible. This is what happens with the great fairy tales. What you think “Little Red Riding Hood” is about when you’re six is not what you think it’s about when you’re 40. The way to tell a story is to say what happened, and then shut up.

When I first started thinking about children’s literature for this talk I found myself surrounded by images of gardens. Alice in Wonderland is full of gardens, and so is Through the Looking-Glass; Humphrey Carpenter called his study of children’s literature of the so-called golden age Secret Gardens, after the novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett. Nursery rhymes sing about them: it was in a garden where the unfortunate maid lost her nose to the blackbird, and Mary, Mary, quite contrary was describing a garden makeover of which Alan Titchmarsh would have been proud.

A garden is a safe place, a pretty place, after all; you’d be happy to let your children play in the garden. And it suggests ideas of growing and cultivation and training, of bringing things up, of nurturing them in the greenhouse to the point where they’re hardy enough to stay outside; and also of keeping them in order, of making sure they look tidy, and so on. There are all kinds of reasons to associate children and their literature with gardens.

So when I was asked to speak about children’s literature I looked for a garden metaphor to start me off, but I couldn’t make it work; because what kept coming to mind was the crazy disordered garden in that little scrap of genius, The Great Panjandrum:

So she went into the garden to cut a cabbage leaf to make an apple pie; and at the same time a great she-bear, coming up the street, pops its head into the shop. “What? No soap?” So he died, and she very imprudently married the barber: and there were present the Picninnies, and the Joblillies, and the Garyulies, and the great Panjandrum himself, with the little round button at top; and they all fell to playing the game of catch-as-catch-can, till the gunpowder ran out at the heels of their boots.

Samuel Foote, 1755

Well, there was my garden metaphor. What could I do with it? This isn’t one of those safe gardens, where all the plants behave predictably; if you want an apple pie here, you have to pick a cabbage leaf. And people can die suddenly—from shock, one presumes. What’s more, dangerous and explosive substances are casually sprinkled around the floor. It shouldn’t be allowed. Someone should stop it.

But of course someone’s trying to: the great she-bear is demanding cleanliness and trying to keep order. She’s obviously one of those security guards in disguise, or perhaps a school inspector, and the only effect she has is to cause the death of an innocent bystander.

But the consolation is that nobody takes any notice at all, and the wedding goes ahead, imprudent or not, and the game of catch-as-catch-can is still going on, as far as I can tell. When I find it, I shall join in.

*

This talk was delivered at the Royal Society of Literature, 6 December 2001.

_____________________________

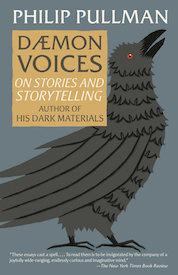

From Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling by Philip Pullman. Used with permission of the publisher, Vintage Books. Copyright © 2017 by Philip Pullman.