In the film business you hate for things to be fucked up at the start. They’ll end up there, it goes without saying. You’re a writer and you’re not stupid, so you know this. Nor is your own relative insignificance in the overall scheme of things in doubt. Films belong to producers for a time, then to directors, and in the end to stars. You? The writer? Forget the yearly Oscar speeches given by actors. Writers are hirelings.

At the beginning, though, for a span of weeks or months, every one pretends otherwise. Really, dude, it all depends on you. You’re wined and dined. If you write books as well as screenplays, you’re told that your last one wasn’t just a good read, it was fucking literature, though the person telling you this hasn’t read it and you know he hasn’t. If you’re not the first screenwriter on the project, you’re given to understand that the whole thing was a clusterfuck because it’s obvious you’re the right guy, the one who understands working-class people, or Ivy League professors, or returning Iraq veterans, or whoever the fuck this movie’s about. It’s all bullshit and you know it, just like you know that in due course you’ll be fired, though probably not by the people flattering you now. By then at least one of these smooth talkers, maybe all of them, will have attached themselves to a more promising project, its financing more secure, its star coming off a hit. Someone new will read your most recent draft and that person will send you an e-mail saying you’ve made real progress in this pass. Shortly thereafter, maybe even the same day, your agent will phone. It’s the call you’ve been expecting for a while, the one telling you the studio has decided to take the project in a new direction, because it turns out you’re not the right guy after all, the one who understands working-class people, or Ivy League professors, or returning Iraq veterans, or whoever the fuck this movie’s about. Now you can go back to your life, to the book you interrupted to take this gig, the one that people on your next film project will claim to admire, though they won’t have read that one, either.

My point is that even though the whole charade is pretty tawdry and transparent, you look forward to it, or part of you does, the part that enjoys being flattered and lied to. The more cynical you are, the more you look forward to it. Which is why I was put off when it appeared we’d be dispensing with this ritual on Milton and Marcus. The initial meeting was supposed to take place in LA, where Jason, who was attached to direct, was shooting a pilot for cable TV. But then Regular Bill wondered if we could meet at his place in Jackson Hole, where he was cutting his recently completed film, Desperation Alley, which was rumored to be overbudget and behind schedule. Anticipating a yes, he’d already flown there along with Marty, his producing partner. Jason suggested that he and I both fly to Salt Lake, rent a car and drive to Jackson Hole. We’d worked together years earlier, when he was young and I was middle-aged. Now he was middle-aged and in another year I’d qualify for Medicare, which was good because I hadn’t worked in quite a while and consequently my health insurance had lapsed. The long, leisurely drive from Salt Lake to Jackson Hole would give us a chance to catch up and maybe talk a bit about Milton and Marcus before we sat down with Marty and Regular Bill. To me that sounded like a good idea. A man can only serve one master, and as far as I’m concerned that’s the director, even when the power behind the project is a Hollywood legend.

Of course alliances between directors and writers are not perceived to be in the best interests of producers and stars, so I wasn’t entirely surprised to learn that Regular Bill had gotten wind of our plan and talked Jason into flying to Jackson a day early, after his pilot wrapped, so he could view a cut of Desperation Alley. My own travel arrangements were left as they were, which meant I’d now have to make the long drive from Salt Lake alone. Marty apologized for the inconvenience, but insisted that once there I’d appreciate having my own vehicle. “Think of it as your getaway car,” he confided. “Bill’s a workaholic. You don’t want to be trapped.”

I was halfway to Jackson when Jason called my cell. “You’re here,” he said, by which he seemed to mean that I was no longer in Vermont. “You’ve got GPS?”

“On my phone.”

“Good. Bill says come up for a drink?” The original plan had been for me to check into my hotel and meet the others for dinner. After all, I’d had an early wake-up call and was still on East Coast time.

“Up?”

“His place is on a mountaintop. Unless you’re too wiped out,” he added, apparently sensing reluctance in my hesitation.

Before I could answer I heard, in the background, the one-of-a-kind voice of William Nolan, unmistakable, even over a tinny cell phone. “Tell him I’ll make him the best margarita he’s ever tasted.”

“You catch that?” Jason said.

I said I had and entered Nolan’s address into my cell.

I was halfway up Nolan’s mountain, two hours later, when my wife called. “You okay?” I asked.

“Of course,” she said. “I told you I would be.” “Is Cassie there yet?”

“She just called from the airport. She’ll be here shortly.” “Did you eat?”

“Some soup.”

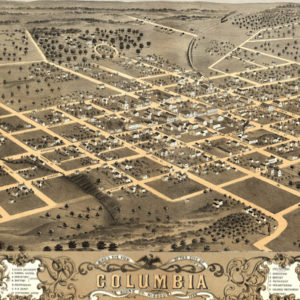

“Look, I’m on a windy dirt road.” At this elevation Jackson looked like a town made out of Lincoln Logs on the valley floor. “I’ll call you in the morning?”

“I’ll be here. I promise.”

Up ahead there was a place you could pull off, so I did. And threw up.

The woman who answered the door looked to be in her mid-forties. She was dressed in a leotard, her upper lip dewy, apparently from a workout. She introduced herself as Tina, and I recognized her from the tabloids as Nolan’s second wife.

“There he is,” said the man himself, rising from the outdoor sofa when I was ushered out onto the deck. He and Jason and a third man I took to be Marty—we’d only spoken on the phone— were in fact drinking margaritas. Nolan was wearing a pair of weathered snakeskin boots, faded jeans and a coarse poncho over a T-shirt that was stretched at the neck. Marty wore a suit, white button-down shirt, no tie. Jason had on jeans and a long-sleeve shirt, not tucked in, boat shoes, no jacket. We were high up and despite the season it was chilly, which made me wonder if Nolan had noticed Jason’s discomfort and offered him a jacket. They were about the same size. Hard to accept a garment from an icon, though. We shook hands all around.

“You arrange that just for me?” I said, because the sun was setting between two peaks, Jackson Hole in deep shadow now, lights in town coming on like jewels on velvet. The private road I’d ascended snaked down the mountain until it gradually merged with the darkness. I recognized the spot where I’d pulled over to be sick. On the railing sat a pair of expensive-looking binoculars. Not the best place to leave them because the deck was built out over the ravine, so if someone accidentally jostled them they’d free-fall a hundred yards before they hit anything. I made a mental note to not be the one to do that.

Nolan held our handshake that extra Hollywood half beat. “I’m guessing you go by Ryan?” he said, my last name, and not guessing, either, since I’d told him that on the phone last week. Still, if he wanted to feel prescient, I had no objection. “You need to use the bathroom?”

A man my age, did he mean, after a long drive? He was fifteen years my senior, though, so maybe he only meant to suggest that he understood if I did. “No, I’m good.”

“I only mention it,” he continued, pointing at my shirt, “because you’ve got a little bit of . . .”

Looking down, I saw what he meant: the word he was looking for was vomit.

By the time I returned, a wet spot the size of a sunflower on my shirt front, Regular Bill had shaken my margarita and was pouring it into a salt-rimmed glass. “Tell me what you think,” he said, which I translated as Tell me what I want to hear.

“Best margarita I ever tasted,” I told him, and no lie, either. “Small-batch tequila,” he explained, topping off Marty’s and Jason’s glasses. “I could almost tell you the exact agave plant it was distilled from.” He consulted his watch. “Time for just one, I’m afraid. We’ve got an eight o’clock dinner reservation in town.” I nodded, letting that sink in. I’d risen at five, flown from Burlington to Boston, from Boston to Salt Lake City, then driven nearly five hours to Jackson. Instead of letting me check into my hotel and catch a short nap, they’d had me drive another half hour to the top of Nolan’s mountain, only to turn around and drive back down again. Good tequila was supposed to make that all right.

“Anyway, it’s not his fault,” Nolan said, returning to the conversation that my reappearance on the deck had interrupted. “The only acting the kid’s ever done is in front of a blue screen. Worse, he has no life experience.”

Unless I was mistaken, they were discussing a well-known young actor who’d made his name in action movies driven by special effects. He’d taken a small but significant role in Desperation Alley. While I was driving from Salt Lake, Nolan evidently had screened the film for Jason.

“Yeah,” Jason said, “but he’s what? Twenty-three?”

“At twenty-three I spent a year backpacking across Europe,” Nolan said.

“Alone?”

“Nah, with this guy Renny. We both flunked out of Claremont the same semester. He’s probably still over there. All he wanted to do was bum around and smoke dope. Which, don’t get me wrong, was fun for a while.”

“Anyway,” Jason said, circling back to the young actor, “he’s not that bad. In your mind’s eye you’re probably still seeing all the bad takes.”

“That’s the other thing. The takes are identical. You say, Let’s try something different, and he says, Yeah, okay, but then he does the exact same thing.”

“Why did you cast him?”

Nolan rolled his eyes. “There must’ve been a reason, or I wouldn’t have done it. Marty. Why did we cast him?”

“You liked the fact that he wanted to be in a real movie,” Marty said. Apparently one of his jobs was explaining Nolan to Nolan. “Also, his name got us green-lit.”

“See?” Nolan said. “I knew there was a reason. Two reasons. That’s one more than I usually have.”

“Two more,” Marty corrected, finishing his margarita and setting the glass down.

Nolan flashed him the smile that, even in his midseventies, still caused women to moisten their panties. “You, too, can be replaced.”

The smile lingered on Marty for a beat, then fixed on me. I assumed the idea was to include me in the joke, but then I realized I’d heard too when he might’ve meant two. For his part, Jason had the look of a man who was fluent in a whole other language where two meant three.

From Trajectory. Used with permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Richard Russo.