In memory of Michael Seidenberg, owner of Brazenhead Books.

For years, I had been hearing about a secret bookstore on the Upper East Side, run by the owner out of his apartment. I thought that you could show up only in the company of a regular attendee. (I would later learn that this was not true, that Michael was, as he liked to say with his trademark this-should-be-obvious-but-nobody-thinks-of-it grin, “in the phone book,” and would happily give his address to any stranger who called him—there were few people more open, less interested in elite status, than Michael.)

One night, I was having a beer with an acquaintance who mentioned he was on his way to the secret bookstore. I tagged along to the unassuming building on 84th St. and heard “Sugar Man” coming from a record player even before we reached the apartment door.

Inside, I was overwhelmed by the books. Pulpy 1950s thrillers stood close to the front, as though to remind you not to get too self-serious in a place that also offered esoteric experimental literature that had been out of print for decades, books you never heard of until Michael put them in your hands and you wondered how you had ever lived without them. The apartment was overstuffed, with books apparently strewn everywhere, and yet somehow their arrangement was so aesthetically gorgeous that, on my first visit and my fiftieth, I could hardly believe it was real. (A friend I later brought to Brazenhead emailed me after hearing of Michael’s death and described the bookstore as “one of those magical disappearing feasts, like in a fairy tale.”)

But the bookstore itself fell away that night once I started talking to the bearded, missing-toothed man behind the bar. Did he tell me about his time as a puppeteer, and did that get us talking about our shared love of Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, or was it the reverse? Michael’s stories and the stories that lined the walls flowed into and out of each other for hours at a time. It was probably close to three in the morning when I got in a cab back to Queens, thinking I had just had one of the peak experiences of my life, not likely to be repeated.

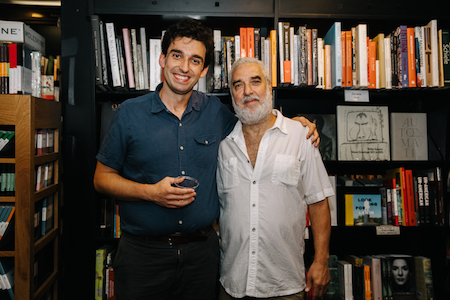

A few days later, he messaged me on Facebook that he had read and loved my first novel, Short Century, which had just been released, and invited me to come to his bookstore for a Q&A. This was a great honor and pleasure, the sort of thing that happens for a writer that you can’t predict but that makes the whole endeavor seem worthwhile.

I started going to Brazenhead all the time with Grace, who was then my girlfriend. We loved having hours-long conversations with Michael, and with people we had never met, some of whom we never saw again but won’t forget, many of whom remain our close friends. When you were at Brazenhead you became a Michaelized version of yourself; your stories were a little more embroidered, you were a little funnier, you felt more comfortable saying embarrassing things. It was difficult to be buttoned up when the proprietor of the establishment usually had most of his shirt unbuttoned, chest hair protruding.

After Grace and I got engaged, we did a champagne toast at his place. On a drunken whim, I suggested that he get ordained to officiate our wedding.

Reader, he married us.

Photo by Sylvie Rosokoff

Photo by Sylvie Rosokoff

One night, he said offhand to me that he had always wanted to be a cult leader. Up to this moment, I had been struggling with my second novel, The Epiphany Machine, which centered around a quasi-cult. I wanted to create a cult leader who wouldn’t feel clichéd or like an easy target, someone I could imagine following myself. With that comment, I saw that my character was right there. I finished the book in just a few months.

The secret bookstore couldn’t remain secret forever; eventually the landlord found out and, after a million packed and sweaty summer farewells, Brazenhead closed.

And then it opened again, a few blocks away in another apartment, and—somehow—at another location upstate. Brazenhead and Michael, it seemed, would live forever.

“What did I think the end times were gonna be like?” This was one of his favorite bleak, wry lines, about the destruction of the literary world, and possibly the world itself, by capitalism. With Michael’s death, the bleakness of this line feels truer than ever, in large part because we no longer have his wryness to counter it. But I’d rather close with a line he used in a promotional video, in which he implored viewers to find his hidden location by opening the phone book: “Come find me and visit me and I’m yours.”

For everyone who found and visited Brazenhead, Michael will always be ours.