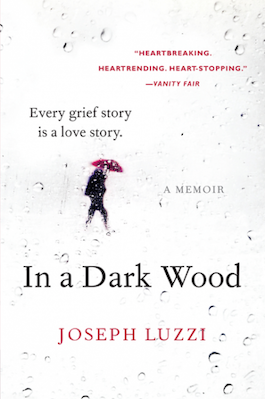

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi rit rovai per una selva oscura.

“In the middle of our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood.”

So begins one of the most celebrated and challenging Divine Comedy poems ever written, Dante’s, a fourteen-thousand-line epic about the soul’s journey through the afterlife. The tension between the pronouns says it all: although the “I” belongs to Dante, who died in 1321, his journey is also part of “our life.” We will all find ourselves in a dark wood one day, the lines suggest.

For me that day came eight years ago, on November 29, 2007, a morning just like any other. I left my home in upstate New York at eight thirty a.m. and drove to nearby Bard College, where I am a professor of Italian. It was cold and wet, the air barely creased by the gray light. After my first class ended, I walked to my office to gather materials and then made my way to a ten thirty a.m. class.

I was joking with my students as we all settled in, when I noticed something unusual out of the corner of my eye: there was a security guard standing at the door.

“Look, they’re coming to arrest me,” I said, laughing. But the beefy security guard was not smiling.

“Are you Professor Luzzi?”

I’ve done nothing wrong, was my first thought. “Yes—why?”

“Please come with me.”

I edged outside the classroom and saw the associate dean and vice president of the college racing up the stairwell. I started running too, down the stairs and out of the building. There was a security van waiting for me.

Joe, your wife’s had a terrible accident.

The words came from somewhere close, but they sounded muffled, as though passing through dimensions. Time and space were bending around me.

I was entering the dark wood.

* * * *

Earlier that morning at nine fifteen, my wife, Katherine Lynne Mester, pulled out of a gas station and into oncoming traffic, just a few miles from where I sat proctoring an exam in Italian. As close as she was, I didn’t hear the crunching blow of the oncoming van into the soft aluminum pocket of her driver’s side door, nor did I see the careening skid of her jeep as it swerved across the country highway and finally came to a full stop twenty feet from impact on the other side of the road. In the monastery-like silence of my classroom, I was unaware of the surging convoy of emergency response vehicles that were barreling up Route 9G, ready to rescue my wife from the tangle of metal and speed her to Poughkeepsie’s Saint Francis Hospital a half hour away.

These emergency responders were not just carrying my wife: Katherine was eight and a half months pregnant with our first child. Soon after the security guard had appeared at my ten thirty class, a medical team performed an emergency cesarean on an unconscious Katherine, delivering our daughter Isabel, who was limp, pale, had no respiratory effort, and whose heart rate was inaudible. The doctors applied pressure ventilation by bag and mask—but one minute into her new life Isabel’s heart rate was still slow and she had to be intubated. Slowly her heart rate rallied. Within ten minutes she was taking her first voluntary, spontaneous breaths.

Forty-five minutes after Isabel was born, Katherine died.

I had left the house at eight thirty; by noon, I was a widower and a father.

* * * *

A week later myself standing in the cold rain in a cemetery outside of Detroit, watching as my wife’s body was returned to the earth close to where she was born. The words for the emotions I had known until then—pain, sadness, suffering—no longer made sense, as a feeling of cosmic, paralyzing sorrow washed over me. My personal loss felt almost beside the point: a young woman who had been vibrant with life was now no more. I could feel part of me going down with Katherine’s coffin. It was the last communion I would ever have with her, and I have never felt so unbearably connected to the rhythms of the universe. But I was on forbidden ground. Like all other mortals, I would have to return to the planet earth of grief. An hour with the angels is about all we can take.

Days afterward, I went for a walk in the village where Katherine and I had been living, Tivoli, New York. By chance I ran into a neighbor who was also out walking: the chaplain who had officiated at my college’s memorial service for Katherine.

“You’re in hell,” she said to me.

I immediately thought of Dante, the author I had devoted much of my career to teaching and writing about. After a charmed youth as a leading poet and politician in Florence, Italy, the city where he was born in 1265, Dante Alighieri was sentenced to exile while on a diplomatic mission. In those first years, Dante wandered around the region of Tuscany, desperately seeking to return to his beloved city. He met with fellow exiles, plotted military action, connived with former enemies—anything to get home. But he never set foot in Florence again. His words on the experience would become a mantra to me:

You will leave behind everything you love

most dearly, and this is the arrow

the bow of exile first lets fly.

No other words could capture how I felt during the four years I struggled to find my way out of the dark wood of grief and mourning. And yet it was only because of his exile that Dante was able to write The Divine Comedy, when he accepted once and for all that he would never return to Florence. Before 1302, the year he was expelled, he had been a fine lyric poet and an impressive scholar. But he had yet to find his voice. Only in exile did he gain the heaven’s-eye view of human life, detached from all earthly allegiances, that enabled him to speak of the soul.

At the beginning of The Divine Comedy, as Dante finds himself lost in the selva oscura—the dark wood—he sees a shade in the distance. It’s his favorite writer, the Roman poet Virgil, author of The Aeneid and a pagan adrift in the Christian afterworld. By way of greeting, Dante tells Virgil that it was his lungo studio e grande amore—his long study and great love—that led him to the ancient poet. Virgil becomes Dante’s teacher on ethics, willpower, and the cyclical nature of human mortality, illustrated by his metaphor of the souls in hell bunched up like fallen leaves. Virgil is his guide through the dark wood, just as The Aeneid gave Dante the tools he needed to curb his grief over losing Florence, whose splendor would haunt him as he wandered through Italy looking for a home during the last twenty years of his life.

That’s beauty’s terrible calculus, I would come to learn: its hold over you becomes stronger after you’ve lost it.

I had met Katherine four years earlier at an art opening in Brooklyn, her tall, elegant beauty standing out amid the slouching hipsters in T-shirts and flannel. She was wearing a form-fitting dress and stood with perfectly erect posture as she drank her champagne and talked with a friend. I made a beeline for her and mustered up the courage to introduce myself. She was kind enough not to sneer at my opening line.

“Nice shoes,” I said, pointing to her spectacular leopard print heels.

“They are, aren’t they?” she answered smiling.

And with these few words my life began to flow in a new direction, one of brief but powerful happiness, the kind that changes you. The crowd buzzing around us seemed to disappear as Katherine told me about her family in suburban Detroit, the father she adored who was a federal judge and a pillar of their community. She laughed as she described her mother, a homemaker who had been raised on a cherry farm and now rankled the family with her unfiltered outbursts on subjects ranging from America’s welfare system to children who pursue artistic careers. I learned about Katherine’s fancy prep school that the family could hardly afford and that she could barely stay afloat in, and her years of fruitless auditions and demos: “My mom says stop doing freebies,” she joked. We walked through the warm October night, first in a pack, then just the two of us. I told her I was a professor, and she repeated the word slowly, looking me in the eye. I don’t know whether she was impressed or just glad to meet somebody from a staid world far from her own. By two in the morning, we were in a cab that would drop me off in Park Slope and then take her to the Upper West Side. But there was a terrible thud, and the car stopped stock-still in the middle of a Brooklyn thoroughfare.

“Sorry, man,” the driver shouted back to us, “we’ve got a flat.”

Katherine and I had fallen asleep next to each other, but now were jolted awake by the noise. Earlier in the evening, I had punched her number into my cell phone, and as we waited for the driver to fix the tire, I couldn’t help but worry that my phone could also experience a mechanical failure, just like the cab.

Later, alone in my apartment, my concern turned to panic: what if I had taken her number down incorrectly? I had no other way of contacting her, no last name, address, or mutual friends. In my southern Italian superstition, I wondered if the jolt from the flat tire was an ominous sign—that I might have lost our connection for good.

Forty-eight hours later, I dialed the number and she picked up on the first ring.

* * * *

Nothing Katherine and I shared could prepare me for the challenges that would come when our allotted time was over. Rilke once wrote that to love another person is our ultimate task, that for which all else is preparation. Only after losing thislove did I grasp his awful wisdom. One of you will have to face the world alone someday and inhabit the Underworld—the hell at the start of Dante’s descent into a dark wood.

A car accident claimed Katherine’s body, but my grief would nearly kill her memory. For the longest time after her death, she became opaque, as an unconscious force deep inside me repressed the things that we had shared. I didn’t try to distance myself from my most intense recollections of her, from the feel of her skin against my own or her smell in the morning as sleep still clung to her. Before I met Katherine I used to believe that love’s chosen space was night, the time for coupling in the dark and dreaming in tandem. But Katherine heightened the start of each day, from the first light that fell on her through the blinds beside the bed, illuminating the dust in chiaroscuro stripes, to the rhythmic weight of her breath, as heavy on my shoulders as her resting arms. Surrounded by her sleeping body, I felt love’s gravity, and it took all of my strength to disentangle myself from her and follow the streams of brightly lit dust out of the bed and into the new day. Slowly but implacably, her death began to transform these living sensations into spectral images—things that haunted my dreams and daydreams, but which I could no longer feel or smell or taste. Grief was a great disembodier.

The insulating shock that kept me from absorbing the full pain of Katherine’s loss also numbed me, preventing me from recalling the full joy of what we had shared. The love we had made, the promises we had exchanged, the plans we had scribbled on Sunday afternoon scraps of paper—grief carried them all away. Only years later, when I began to write about this lost cache of memory, would I learn that to survive Katherine’s loss I had to let her die a second time, in my thoughts and dreams, so that the pain would not paralyze me.

The day of her accident, part of my shock was tempered by the calming thought that I could speak with her later that night in spirit—after all, our relationship had been cut short almost mid-conversation. But these one-way dialogues offered only the coldest comfort; I needed a guide, someone who knew how to speak with the dead. Someone who had written about life in the dark wood.

The Divine Comedy didn’t rescue me after Katherine’s death. That fell to the support of family and friends, to my passion for teaching and writing, and above all to the gift of my daughter. Our daughter. But I would barely have made my way without Dante. In a time of soul-crunching loneliness—I was surrounded everywhere by love, but such is grief—his words helped me withstand the pain of loss.

After years of studying Dante, I finally heard his voice. At the beginning of Paradiso 25, he bares his soul:

Should it ever happen that this sacred poem,

to which both heaven and earth have set hand,

so that it has made me lean for many years,

should overcome the cruelty that bars me

from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb,

an enemy to the wolves at war with it . . .

I still lived and worked and socialized in the same places and with the same people after my wife’s death. And yet I felt that her death exiled me from what had been my life. Dante’s words gave me the language to understand my own profound sense of displacement. More important, they enabled me to connect my anguished state to a work of transcendent beauty.

After Katherine died, I obsessed for the first time over whether we have a soul, a part of us that outlives our body. The miracle of The Divine Comedy is not that it answers this question, but that it inspires us to explore it, with lungo studio e grande amore, long study and great love.

From IN A DARK WOOD. Used with permission of Harper Wave. Copyright © 2016 by Joseph Luzzi.