On May 13, 1902, the Guardian sponsored a rally at Faneuil Hall in support of the Fourteenth Amendment and congressional investigation of southern disfranchisement. The event called itself the Crumpacker Rally in honor of the Indiana Republican Edgar D. Crumpacker, who wanted Congress to reduce southern representation in those states where black citizens were denied the right to vote. Crumpacker, and fellow Pennsylvania Republican Marlin E. Olmsted, invoked Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which allowed Congress to reduce representation in those states that denied citizens’ rights. Olmsted introduced this resolution on January 3, 1901, less than three months after Republicans took control of the White House and both houses of Congress in the 1900 elections.

Crumpacker had worked on the resolution months before the presidential election, mainly in response to widespread white violence against black voters across the South. In 1898, for instance, mere months after Frazier Baker’s murder, five hundred white North Carolinians, angry at the predominantly black city of Wilmington for electing Republicans to the state legislature, stormed the town hall, seized control of the city council, and attacked black people and their businesses in a violent political coup. Although the new, white Democratic Wilmington government clearly violated the Fourteenth Amendment, neither state nor Federal officials intervened, allowing the “Old North State” to fall under Democratic control with little attention outside of the black community.

As a GOP loyalist, Crumpacker recognized that suppression of the black vote meant continued Republican losses across the South. And as chair of the Congressional Census Committee, he was also aware how election results in southern districts reflected white violence and voter suppression rather than the will of black voters, most of whom were either disfranchised through revised state constitutions, or violently suppressed by white mobs. Crumpacker designed the legislation in early 1899, but he tabled it in June 1900 out of respect for the incoming McKinley administration—he wanted to avoid the inevitable white backlash that could cost the party either the White House or Congress in November.

Even as Crumpacker’s proposal to implement the Fourteenth Amendment spread across the South, white Democrats cockily declared that rumors of Federal protection for black voters were just that. As the Richmond Dispatch reported, “we do not think that the south need lose any sleep over Mr. Crumpacker’s threat.”

On January 7, 1901, however, when Crumpacker did follow through with his “threat” by submitting an amendment to the congressional reapportionment bill that denied three seats each for Mississippi, South Carolina, Louisiana, and North Carolina, Democrats responded with obstruction, while Republicans refused to even speak on the issue. In fact, only three congressmen supported Crumpacker’s amendment. By the time William McKinley took his oath of office in March 1901, Congress voted to apportion its members in accordance with the 1900 Federal Census, but it refused to consider Crumpacker’s resolution or account for the glaring fact that southern states gained representation at the same time that they disfranchised black citizens.

Undeterred, Crumpacker reintroduced his legislation on June 3, 1901, but obstruction by white Democrats, and apathy by Republicans from across the country, was swift and decisive. Democrats, led by Alabama’s Oscar W. Underwood and Mississippi’s John S. Williams, sent the resolution back to committee when they determined that it made no distinction for why voters were disfranchised. They maintained that disqualifying voters due to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” was very different from standard “educational and poll tax requirements” passed throughout the former Confederacy since the 1880s.

Monroe Trotter made enforcement of Federal civil rights a populist movement, led and orchestrated by the masses of “genteel poor” who Booker T. Washington tried so desperately to disavow.But Crumpacker refused to back down—he offered an amendment, calling for the loss of three House seats each for Mississippi, South Carolina, Louisiana, and North Carolina. According to official US Census records, black voters in these states were disproportionately disfranchised, given their numbers in the population.

For Monroe Trotter, the Crumpacker resolution and the ensuing battle by Massachusetts congressmen to resurrect legislative enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment proved the necessity of a reinvigorated movement for political independence and black-led civil rights protest. The fact that Massachusetts’s only contribution to Crumpacker’s fight came from John Fitzgerald—the Democratic son of Irish Catholic immigrants who dropped out of Harvard Medical School to support his impoverished family—proved the ignorance of blind allegiance to party rather than principle. Booker T. Washington and T. Thomas Fortune’s public opposition to attempts by Massachusetts congressman William Moody to revive Crumpacker’s bill further proved that black people, not their leaders, should be entrusted with civil rights protest.

Moody, who left Congress in 1902 to become President Roosevelt’s secretary of the navy, took Crumpacker’s legislation a step further by calling on Congress to investigate southern suffrage laws. If those laws were unconstitutional, Congress would deem them null and void, and if they were not, Congress would still enforce the Fourteenth Amendment by reducing state representation if suffrage laws continued to deny citizens’ rights.

Even more frustrating for Trotter was the fact that, in opposing such legislation, Booker T. Washington acted with the same duplicity that characterized his approach to the Thomas Harris case in 1895. Back then, public conciliation to white Alabamans took precedence over assistance for a black man attacked merely for exercising his civil rights. Now, in 1901, support for the conservative notion that southern states could deal best with the “negro problem” excused Federal neglect of the Fourteenth Amendment, even as Washington worked behind the scenes to pass stronger antilynching legislation.

This last project involved white Boston liberals who were conspicuously silent on Crumpacker and Moody, including Senator George F. Hoar and former abolitionist Albert Pillsbury. Pillsbury wrote legislation to prosecute all lynching participants for murder under Federal, rather than state, jurisdiction, and Senator Hoar submitted the Pillsbury Bill to Congress in 1901, where Moody offered his unqualified support. Pillsbury wrote frequently to Washington about the measure while the two worked, privately of course, to pass antilynching laws in Louisiana. Publicly, however, neither Pillsbury nor Hoar countered prevailing conservative rhetoric about the evils of “Federal interference,” and the supposed “ignorance” of the negro.

But Monroe Trotter believed congressional enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment should be supported, publicly and passionately, and that black people themselves should lead the charge. And so he fired the first shot in his Guardian arsenal from Faneuil Hall, where colored Bostonians, “and all those concerned with the cause of justice” let the world know that they would not back down in the face of political apathy. Beneath the same Doric columns and bay windows under which his father spoke following Benjamin Butler’s triumphant ascension to the state house, Monroe Trotter made enforcement of Federal civil rights a populist movement, led and orchestrated by the masses of “genteel poor” who Booker T. Washington tried so desperately to disavow.

Monroe started by advertising the May 13 Crumpacker Rally in the Guardian, which mobilized black radicals to publicize the pending legislation at church, through settlement houses, and at community events. As a result, the Faneuil Hall rally mixed “radical” lawyers and former Federal officeholders like Archibald Grimke with black community organizers like Woburn minister William H. Scott and Cambridge pastor S. Timothy Tice. Scott and Tice had particularly strong ties to the genteel black poor across greater Boston. A former Virginia slave who escaped to the Twelfth Massachusetts Regiment at the age of 14, Scott attended Wayland Seminary, pastored churches in Virginia and Brooklyn, and opened a bookstore in D.C. before he moved to Boston in 1895. By 1900, Scott pastored an all-black church in Woburn, where he had long argued that radical support for Federal civil rights was the only route to racial equality.

At the Faneuil Hall rally, where he served as permanent chairman, Scott declared that his Racial Protective Association had one purpose—“to unite ten million Negroes of this country in one purpose of regaining their rights.” Through Scott, the Crumpacker Rally attracted black working people from outside of the city, particularly in the small towns surrounding his Woburn church.

Reverend Tice was another radical who brought the black genteel poor with him to Faneuil Hall. A “negrowump” editor in his native Annapolis, Tice was an AME Church leader who pastored congregations in Maryland and eventually left Massachusetts to lead a church in upstate New York. Less than a year in to his leadership at Cambridge’s St. Paul’s AME, Tice published a scathing attack on William Hannibal Thomas, a black author who called for wholesale disfranchisement of his race. As committed to the rapidly expanding black community in Central Square as he was to national reclamation of civil rights militancy, Tice created the St. Paul Social Settlement to provide black migrants with domestic training, women’s clubs, nursery schools, and employment contacts.

From the settlement’s headquarters on Hastings and Portland Street in Cambridge, Tice mobilized black working people around the Guardian’s cause when he personally escorted them across the Charles River to Faneuil Hall for the rally. Tice then received raucous applause and a chorus of “amens” from the audience when he called the meeting to order with a rousing speech about the desperate need for Federal civil rights enforcement.

The Faneuil Hall rally included a diverse cross section of the black public.“Too long split and divided by the trimmers and compromisers in their own ranks, the Negroes of Massachusetts, and the Negroes of the entire country, are fast becoming united against the traitor within and the enemy without,” Tice shouted. “We believe a Black American has as much right to vote as a White American; that the Negro should resist actively and with every means at his command the taking away of his civil and political rights.” Stressing racial unity against “Negro race trimmers” and the “politicians or chief executives” who supported them, Tice explained to the crowd that they must appeal to the Constitution for their Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment rights.

Despite such enthusiasm, the Crumpacker resolution did not make it through Congress, and another antilynching bill, based on the constitutional arguments made by Albert E. Pillsbury and George Hoar, would not appear for nearly two decades. Still, the Guardian’s Crumpacker Rally, which attracted overflowing crowds to Faneuil Hall, established Monroe as a significant force in Boston politics. Unlike the Afro-American Council, the Faneuil Hall rally included a diverse cross section of the black public—colored people from Cambridge to New Bedford, attorneys as well as passionate janitors and bootblacks.

Reporting on the Guardian’s activities for Booker T. Washington, Harvard student Roscoe Conkling Bruce groaned that the paper was devoured by “the malcontents whose doctrines it expresses, by the curious whose curiosity it feeds, and by the rather large lower middle class of Negroes who yearn for a lively race paper in Boston.” Because these “lower middle class” negroes made up the vast majority of black Bostonians, Bruce complained that “Forbes and Trotter aren’t likely to be losing any money.”

What Bruce dismissed as a money-making rag sheet marketed to black “malcontents,” however, black Bostonians saw as a popular vehicle for political mobilization. As such, they stood side by side with Archibald Grimke, Butler Wilson, and other professional men at Faneuil Hall, galvanized by Trotter’s insistence that the Guardian wanted “laws enforced against the rich as well as the poor, against the capitalist as well as the laborer: against white as well as Black.”

The Faneuil Hall Crumpacker Rally also revealed that Trotter and the Guardian could attract white liberals who had either been indifferent to, or quietly supportive of, Booker T. Washington. In the same letter to Washington, describing the Guardian’s “lower middle class” readers, Bruce lamented that the paper “might exert some slight influence over the white people [in New England].” The fact that the congressman and other influential white legislators wrote letters of support to the Guardian indicates that Bruce’s concerns about Trotter’s influence on white liberals were accurate. In just six short months, Monroe managed to turn the cultural capital accrued through his Hyde Park childhood and his time at Harvard into a level of political respect that Booker T. Washington worked over twenty years to cultivate.

In addition to Crumpacker’s letter, the Guardian received notes of encouragement, and apologies for their absence, from Massachusetts governor Winthrop M. Crane, ex-governor George S. Boutwell, and leading constitutional lawyer Moorfield Storey. The meeting closed with a list of resolutions, read by New Bedford activist Edward B. Jourdain, which demanded congressional investigation of southern election laws, immediate passage of the Crumpacker resolution, and black New England voters’ refusal to endorse or caucus for any candidate who did not support these resolutions.

____________________________________

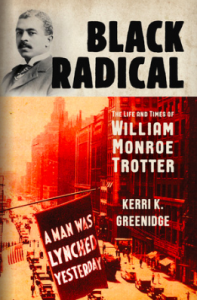

From Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter by Kerri K Greenidge. Used with the permission of Liveright. Copyright © 2019 by Kerri K Greenidge.