For poet and photographer Jen Fitzgerald “‘a series of unfortunate events’ began unfolding. And in New York City, we don’t have cushion to handle one unfortunate event, let alone twelve.’” She is now one of nearly one million New Yorkers who may be unable to pay their rent and are thus at risk of eviction during the pandemic.

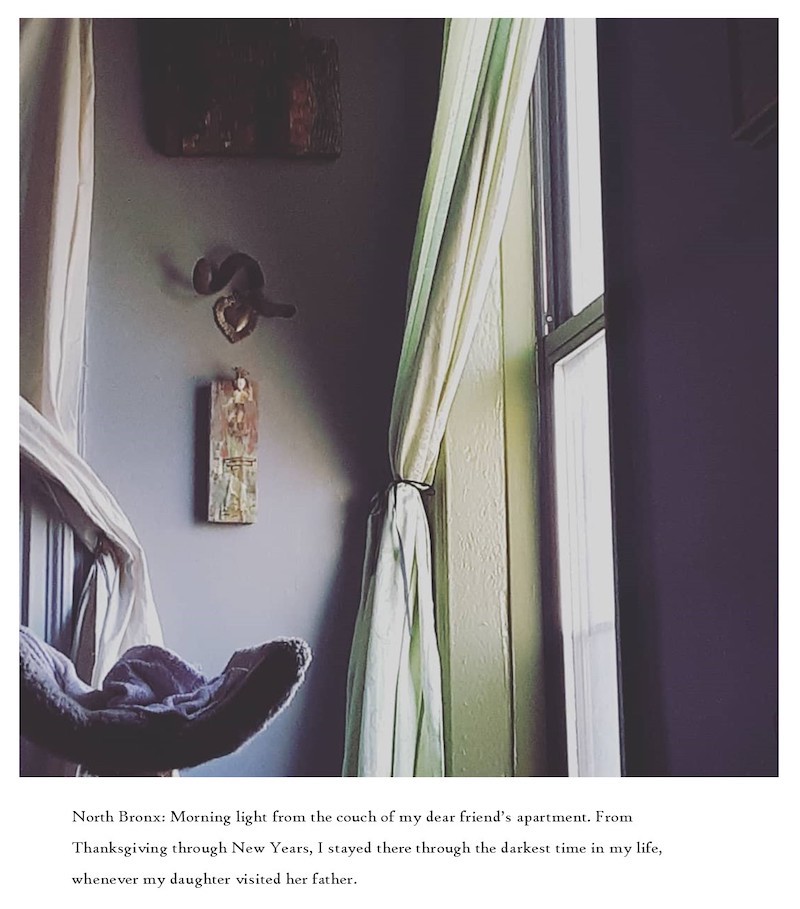

It started even before Covid-19 landed in March. But it worsened then, when the Airbnb Fitzgerald stayed at was swiftly no longer a housing option. She was unable to afford another month upfront, Fitzgerald says.

She grew desperate. A single mother, Fitzgerald was also unable to return to work for the foreseeable future due to the coronavirus, as she teaches poetry and writing in New York City’s jails including Rikers Island, places that have been epicenters for infection. Fitzgerald’s other profession is writing poetry—she was previously the author of a 2016 poetry book, The Art of Work about the members of New York City’s Butcher’s Union, UFCW Local 342, including her own family—but poems do not pay by the word. Eventually, Fitzgerald created an open call on social media to her friends asking for support.

But Fitzgerald was able to put this experience to some use in the fact-based poems and personal images that follow. “My difficulties did not start with the coronavirus but the virus is showing me that there is actually a level of struggle that is simply not possible to contend with,” as Fitzgerald puts it.

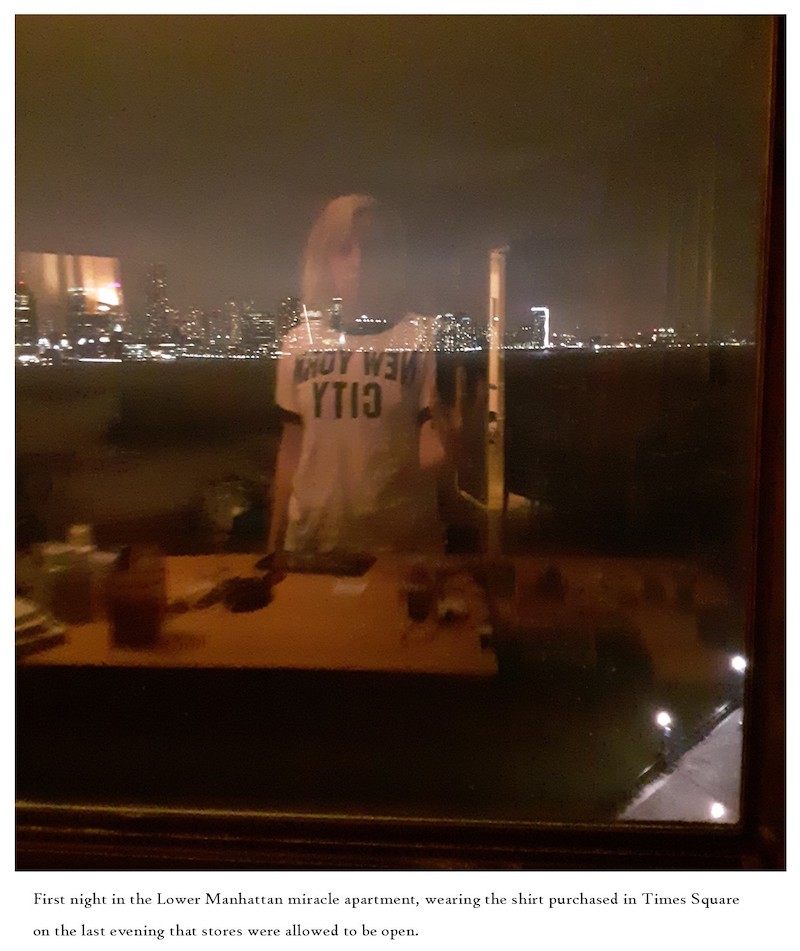

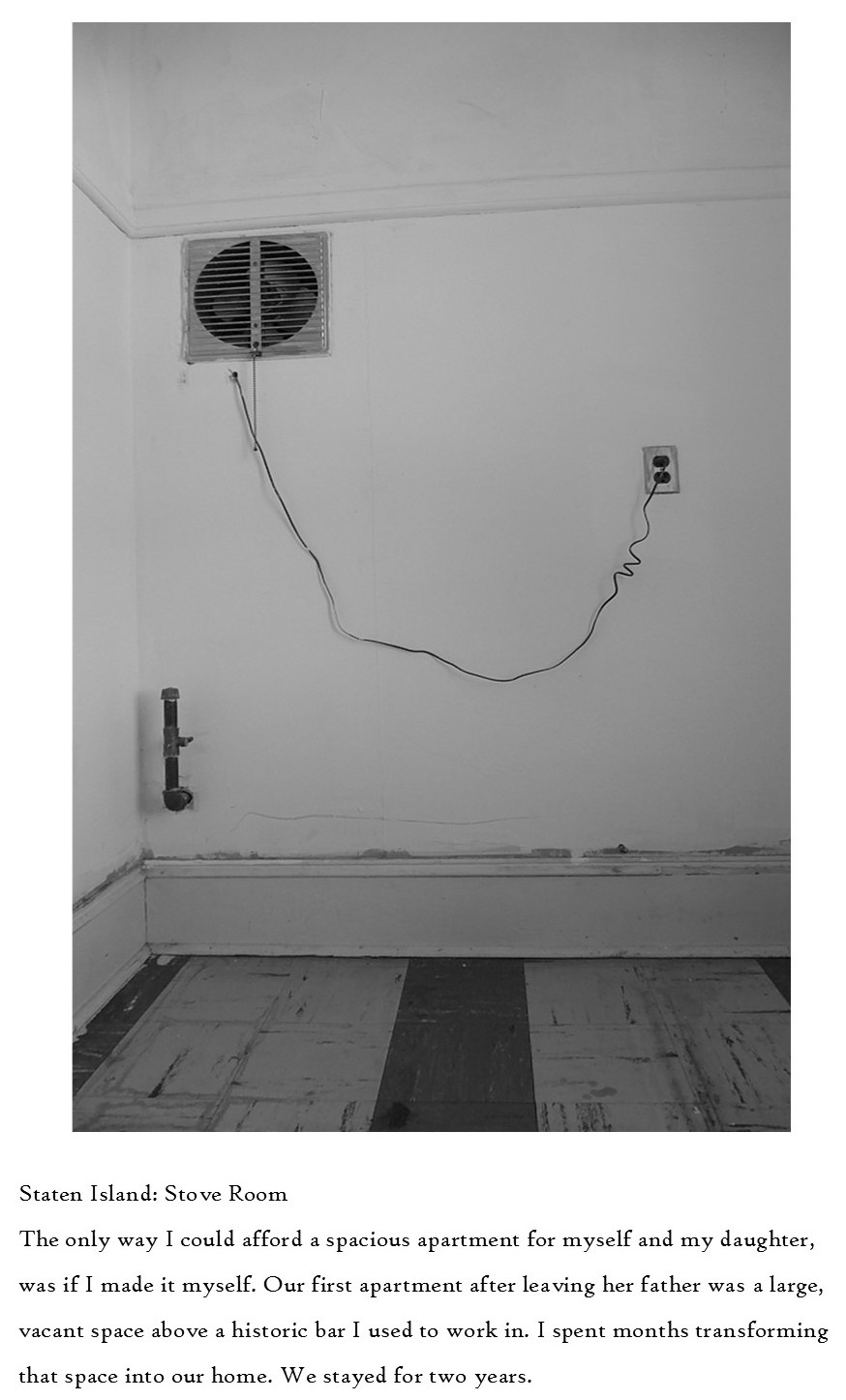

Fitzgerald was born and raised in New York’s Staten Island. Thanks to her social media outreach Fitzgerald was introduced via a friend to friends of hers who had left their lower Manhattan apartment vacant during the quarantine. “The open minds and open hearts of this couple astound me,” she says. She and her daughter are currently living rent-free in the donated vacant apartment. They will have to leave soon, however.

For other cost of living expenses, Fitzgerald has, as she puts it, been battling “the Unemployment Ins. gods since April 6th.” She waited for the money to arrive with “millions of other New Yorkers: calling, calling, waiting, calling.” Fitzgerald’s unemployment money came through toward the end of May.

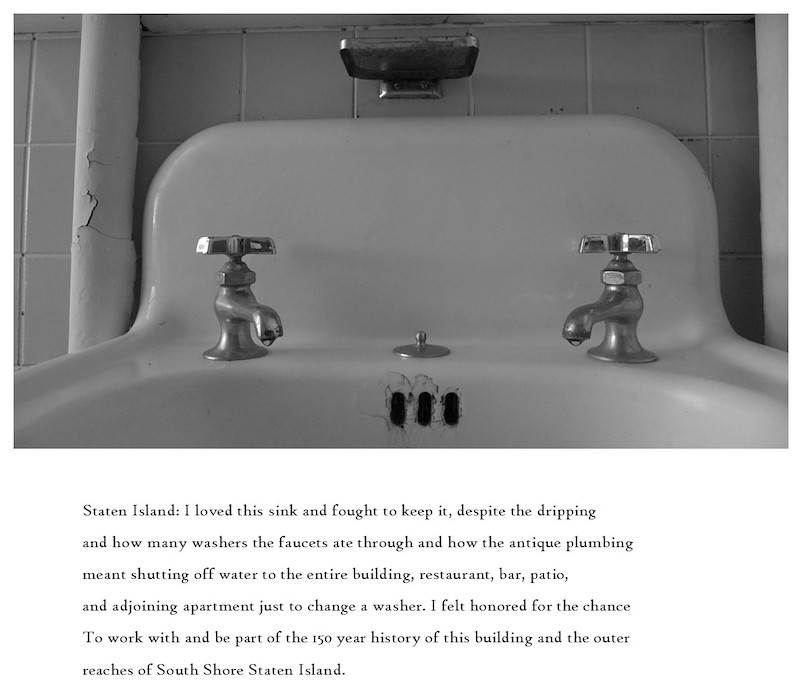

In addition, protests against police violence as well as the effect of Covid-19 on communities of color have roiled American public spaces in recent weeks. These protests, and the experience of housing instability during a health crisis, have edged into the poems and images that follow. They stand as testaments to the wearying nature of eviction and homelessness. They are also records of what it is like to be alive in an extreme time and place, accompanied by Fitzgerald’s photos. Fitzgerald says they are examples of her “feeling out this new reality.”

In German, the word uncanny, umheimlich, a favorite word of Freud’s, also means “unhomey.” These poems show how synonymous the uncanny—or the disturbing—and the loss of our homes, really are. For Fitzgerald and so many others in American cities, no longer having or being pushed out of their homes during a national crisis is strange indeed.

“The city is opening back up and my continued presence will quickly morph from ‘crisis help’ to ‘free-loading,’” says Fitzgerald. “I am keenly aware of that and am too grateful for this help to ever cross that threshold.”

“I do not know where I am going, but I know I am going to start heading there in a couple of weeks,” says Fitzgerald of her and her daughter’s future.

–Alissa Quart

*

American Landscape: Inheritance

This is not a poem

about losing an apartment

nor is it a poem about losing

three apartments in three months,

which I could write for you

with deftness; this is not a song

for my job long gone, I’m afraid

this is an answer.

I’ll not be so bold as to insert myself

into 200 years of the dream—

of who still dreams it

and who still comes,

of who was born in it

and what’s been done

but geography is fate

and I’ve been here

far too long for gratitude

in the immigrant city,

of the immigrant nation—

after five generations,

the best I could do

was a single room

and some money for food

If I am an answer

then is failure my question?

My images, like my lineage: too grand—

but I am the song my ancestors sang

on their ocean voyage West;

raised on the Statue of Liberty

and the Irish starving in the streets;

raised the impossibility of survival.

I can’t make allegory of an entire life;

at some point I will have to start living.

But I remain at the impossible nexus:

five generations in and ousted

cannot be dressed up in eloquent language, poet.

Disinherited, at last!

from the monolith

I am afraid, but in that fear,

liberation, I tell myself—

because even my homelessness

must have glory written in the margins.

When My Daughter Writes the Poem of this Day

I will be distant—in black and mourning; I will be leaning

into the open window as I drive us up and over; hauling

only what we could carry, through three boroughs; I tell

myself she will remember nothing I want her to forget

as though I could shield her from failures I call attempts;

these formative failures I swore to never—forgive me;

not all scenes can be painted in favorable light; she sees

the view from back seat, clenched jaw, my rising tide;

forgive me; for some of us, grief is unshakable anger—

it takes up residence within us; for we well-practiced few,

anger throws us into the dust of the new; forgive me;

I have dragged my child into my childhood where I was

more wildflower than girl, cast to soil by wind; rootless

yet never free; incapable; me, again—me again, here now—

somehow not just me; forgive me; I burned through all

the saints and call on any deity that will have me, let her

painlessly unsee all but my hair catching wind as a bright

but tenable flame, let her remember me only as the woman

who carried water up the hill for everyone to finally drink.

The Heart Divided Has Many Rooms

1.

Of the normally four walls that comprise a room,

Of the plaster, lathe, gypsum, gas lines veining the lamp-lit walls,

Of the layers

the layers of paint, paper, poster,

we decorate vacancy

Of the pine floors,

the stripped, peeled, stained, patched—

Of the necessary steps we take

to not be too many steps away—

but that’s how they get us—

the absurdity of structure

and our inherent tenancy;

Of walk up, of split level, of detached, semi-attached two family

Of costs that defy reason—

that’s how they gut us.

And we let them,

all to prove,

I will do whatever it takes

to stay with you

2.

what language

have we made

for each other?

I am afraid I don’t know what to say

I am afraid I shouldn’t say

and afraid not to say

the heart divided has many rooms

3.

my claim to this city

has nothing to do with birth

but that I have loved

and laid my head

in every borough.

I am native;

you cannot evict me

from the people

who sustain this heart divided

4.

words obfuscate meaning, so I will do my best:

This vision is no city without you

no country

no heart;

a vacant lot,

absent your voice

I may not know what we look like

after all this burning but

I will sit with you in the rooms of this heart;

we’ll eat from a charred table,

view our scorched street

through singed curtains, eat of whatever is left—

hear me: anything, anywhere, but only with you

__________________________________

Jen Fitzgerald is a poet, essayist, photographer, and a native New Yorker who received her MFA in Poetry at Lesley University and her BA in Writing at The College of Staten Island (CUNY). Her essays, poetry, and photography has been featured widely, over the past decade, in venues such as <em>PBS Newshour, Tin House, Boston Review, NER, Colorado Review</em> among others.