My daughter would sit on my lap while I read to her. We rocked in the gliding chair my grandmother gifted us when she was born. We preferred stories with a plot to those with pictures and “baby’s first words.” She sat in the space between my elbow and shoulder.

She loved Dragons Love Tacos. When I read it I stressed the word “love.” I pushed the “O” sound with a little inflection at the end, “loooooooooOOve.” Each night she pointed and asked if we could read it first. She’d imitate the gurgling sounds I made when the dragon with an upset stomach appeared on the page. We fell into a rhythm. After we finished, she’d ask to read it again. And again. I started hiding the book.

Her other favorite was The Love Monster, which is about a monster who can’t find anyone to love him because he’s ugly and a little funny looking in a world filled with cute and fluffy things like puppies and kittens. After looking everywhere, including a place where a tumbleweed rolls past him, he finds someone while getting on the bus to go home. Sometimes all it takes is a little waiting and a little luck to find the right person at the right time.

My son was born a few months after my daughter’s second birthday. He arrived with less patience and interest in books.

I tried to read to him, but wrestled in my arms for freedom. After months of trying, he sat through Little Blue Truck. He loved how the truck went “Beep! Beep! Beep!” He liked the farm animals and noises they make. He enjoyed the toad saving the day. But how many times can a parent read the same book? More than I thought.

As he grew into a toddler, my son decided to play instead of read books with his sister at night or at the kitchen table during breakfast. He preferred running wild until he passed out. He’s me as a small child—the energy and the desire to explore and push boundaries. He wants to climb up my back and jump on me.

Finally, I found another book that caught his attention: Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. I’d read the book to him before, but one evening, when he was two, he saw what I saw as a child.

*

Published in 1963, Where the Wild Things Are won the 1964 Caldecott Medal, which is awarded by the American library association for the most distinguished American picture book for children. At the time, though, Sendak’s book horrified some parents. His Wild Things are big, scary monsters. The protagonist is a little boy named Max who tells his mother he will “eat” her up.

One of the people offended by the book is my sister-in-law. I gifted a copy to her when she had only one of her six children. Twelve years later, I found out she hated it. She thought Max was a mean and disobedient child. We disagree. He’s not a kind boy, or obedient, but that’s the magic of the book: no child is perfect. If they are then I’m terrified. Instead, there’s something honest about Max. As readers, we venture into his psyche.

The Wild Things are manifestations of Max’s fears. He knows he wronged his mother. He’s dreaming to discover an answer for his behavior and punishment—being sent to bed without dinner.

“Far too many contemporary picture books for the young are still populated by children who eat everything on their plates, go dutifully to bed at the proper hour, and learn all sorts of useful facts or moral lessons by the time the book comes to an end,” Nat Hentoff wrote in a profile of Sendak for The New Yorker in 1966. “And any fantasy that may be encountered either corresponds to the fulfillment of adult wishes or is carefully curbed lest it frighten the child. Many of these books, homogenized and characterless, look and read as if they had been put together by a computer.”

Parents want their children to listen. With that, they hope the kids on the pages of the books they read will act as if they’re under a spell and that any “bad” kid will get their comeuppance. Children’s books don’t exist in reality. They both don’t want to offend the readers (parents) or hypothetically scare the children. They don’t acknowledge that children live in the same world as adults but their experiences are limited so they don’t know how to be scared or how to react to such monsters as “Wild Things.” To them, the world is mostly imagined and they fill in the gaps between what they do and do not know with things like monsters and nightmares.

I felt this as a child without knowing it. I connected with “Where the Wild Things Are” because I recognized Max’s anger. I could see the story unfold and feel Max’s emotions move with it. I understood where the Wild Things arose. I sensed that rage, the desire to have nonstop fun, to be in charge. As an adult who reads to his children, there is often something missing in a children’s book where the character does everything right. The stories forced and diluted. They’ve been Disney-brain-washed with happy endings and uncomplicated characters with simple motivations. Not Sendak’s books. He refuses to give in to parents and their wishes. Instead, he believes and thinks from a child’s point of view. He acknowledges their feelings, which grants his characters levity.

“Adults who are troubled by it forget that Max is having a fine time. He’s in control. And by getting his anger at his mother discharged against the Wild Things he’s able to come back to the real world at peace with himself,” Sendak told Hentoff. “I think Max is my truest creation. Like all kids, he believes in a world where a child can skip from fantasy to reality in the conviction that both exist.”

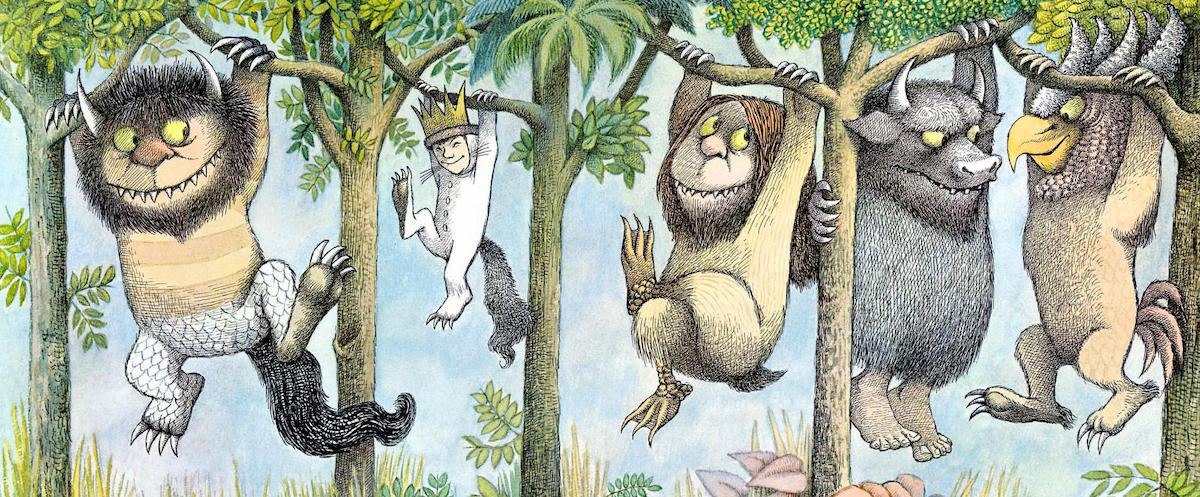

Where the Wild Things Are unfolds with Max’s imagination growing and each picture expanding with it. The illustrations increase in size until the middle of the book, when Max is named King of the Wild Things and starts the “rumpus,” and the pictures take up both pages. Then they begin to shrink as his imagination wears out. The book has an uneven edge to the drawings. “When one of his lines for a drawing is blown up, you find that it’s not a precise straight line,” Hentoff writes. “It’s rough with ridges, because so much emotion has gone into it.” The pictures have feeling and sense of spatial understanding that most children’s books don’t. Reality has its own edges and Sendak’s drawings bring that to life. Nothing is easy and the pictures we remember are often muddled and half put together memories or dreams.

Even when my son doesn’t want to sit and read, even when he protests Where the Wild Things Are in favor of jumping or bouncing, he stops when I start to read. He places his head and his long blonde hair on my chest. When we reach the rumpus, we have a series of sounds we make. We howl like a wolf like Max and the Wild Things as they howl at the moon. We say, “Weeee” as they swing from branches. I begin to sing “When the Saints Go Marching In” when they have their parade. He never questions Max’s room turning into a jungle. He never questions the boat tumbling by and the room transforming back again.

“What I don’t like are formless floating fantasies. Fantasy makes sense only if it’s rooted ten feet deep in reality,” Sendak said. “In Where the Wild Things Are the reality is Max’s misbehavior, his punishment, and his anger at that punishment. That was why he didn’t just have a cute little dream. He was trying to deal with imperative, basic emotions.”

A child’s life is filled with anxiety because they don’t know or understand what’s around them. The spectrum of basic emotions is enhanced because of their lack of experience. It’s the opposite of being an adult who has information and history to ground them. Each time we read the book, though, I can see how my son relates to Max. How I related to Max. How we both want to run up and down the stairs and chase the dog. How we imagined ourselves somewhere else. How we saw monsters and how we want to tame them.

“I refuse to lie to children. I refuse to cater to the bullshit of innocence.”In Max I see a boy not being mean or rude, but a child searching for their place and that place just doesn’t mix with what their parents want all the time so he lashes out in a fit of rage and is eventually sent to bed. Neither of us will sit still and neither of us have any inclination to want to read or learn. I saw in my son the beginning of my own journey to finding stories and reading.

In kindergarten I refused to learn to read. I didn’t show much of a desire before either. As a baby and toddler my mother would try to read to me while I sat on her lap and I’d wiggle free. I preferred to jump and run. I wanted to climb on the refrigerator and hide.

That changed in kindergarten when I discovered I was placed in the “slow group,” not with the kids I wanted to be friends with. I decided to learn to read. I went from the bottom group of readers to an honors student. I hung on to that track by doing just enough for years. I worked with acceptable effort not to get in trouble, never to excel.

*

Maurice Sendak began to illustrate as a young child. His older brother wrote the words to the stories he drew on cardboard from the inside of a new dress shirt. The writer Gay Talese famously used the same boards to take notes when reporting because they offered room to write and folded nicely to fit into a jacket pocket. Sendak’s sister bound the stories for him.

The earliest stories weren’t happy because Sendak wasn’t a happy child. Most of his extended family was killed during the Holocaust and he was scared of the relatives he saw. The ones who visited every Sunday scared and scarred him. “I hate them all. They were grotesque.” Sendak told the Chicago Tribune in 1990. They served as inspiration for his Wild Things.

Sendak had an interest in children from a young age. He would sit and watch children play and interact with adults. His own childhood wasn’t great, though. He was a sick kid with a mother who could enter into her own dark moods that lingered. He had his own depression to deal with too. The world seemed dark and dangerous. Especially for him, a gay man in American in the middle of the 20th century.

He could peer into the fears and lives of children because he had to live in a dream state all his life. He hid his true self from the world. His parents didn’t know he lived with his partner until his death. He didn’t tell the world until after his partner died in 2007. “All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy,” he told The New York Times in 2008. “They, never, never, never knew. Children project their parents.”

A curmudgeonly man, Sendak’s vision of the world flowed into his work. He never made it magical or wondrous in a way that had rainbows and unicorns popping out of thin air to solve every problem. The characters in the stories he wrote and illustrated needed to discover something on their own. They needed to explore the world and find their way. They needed to draw their own conclusions and paths. Life isn’t easy, but children survive.

After we read, I lay down with my son until he falls asleep. He needs someone to help keep him in his bed.“It is always amazing to me that children survive childhood, that they go on to have professional careers and run countries,” Sendak told the Tribune. “I think it’s due to their tremendous courage. They have to be very brave. And that loyalty and courage and bravery is the subtext of everything I have ever written.”

*

Each night before bed we go through the routine: bath, pajamas, brush teeth and hair and books. There’s the fighting over cleaning up messes from the day of play. I lay flat on my back with my eyes closed. Sometimes I drift to sleep for a few minutes and wake to a child jumping on my stomach. The kids get to pick from the bookshelves upstairs. That’s the good one, filled with the books their parents want to read. We sit down, either my wife and the kids or me and my kids, and read.

After we read, I lay down with my son until he falls asleep. He needs someone to help keep him in his bed. Otherwise he will stand in his doorway and yell to his sister, calling her name over and over again for hours. He bangs and jumps. He climbs on furniture. My daughter sits in her bed with stacks of books and a small reading light. She stays up for hours parsing through them, telling herself the stories.

After my kids go to bed, I sit on my couch and open a book. I don’t have as much time to read as I did before children and life, but I find the moments. Usually, though, I read a few pages and drift off to sleep. Too tired. Too worn out. But, without the books, I’d stay up all night doing chores, cleaning or watching television.

*

For Maurice Sendak the fantasy of his books was never a lie. That fantasy exists in us all. The stories live in us. There’s no hiding from our imagination, especially a child’s imagination.

“I refuse to lie to children. I refuse to cater to the bullshit of innocence,” Sendak told The Guardian in 2011.

There’s no greater clue to this kind of thinking than in Sendak’s final interview with Terry Gross that same year. Sendak, 83 at the time, was struggling with what the end of life looked like. He’d completed his final book, Bumble-ardy, and was doing the usual book tour. With Gross, who has an ability to crumble barriers put up by the most dedicated subjects on her show Fresh Air, Sendak broke from the usual book tour mantras of what life was like. He held up no facade. He could not lie. While working on the book, Sendak’s partner died and he found an escape from death in creating art.

“Since I don’t believe in another world, in another life, that this is it,” Sendak said. “And when they die they are out of my life. They’re gone forever. Blank. Blank. Blank. And I am not afraid of death.”

Later, Gross pushed him on his atheism. Was it still strong?

“Yes,” Sendak said. “I’m not unhappy about becoming old. I’m not unhappy about what must be. It makes me cry when I see my friends go before me and life is emptied. I don’t believe in an afterlife, but I still fully expect to see my brother again. And it’s like a dream life. But, you know, there’s something I’m finding out as I’m aging: that I am in love with the world.”

*

My son enjoys books now. He asks me throughout the day to read to him. He will pick a few books out and bring them to the table or the couch. At night, he will pick out a pile of books. From time to time I’ll even find him at peace in a corner looking at books. I’ll peer in and make sure not to disturb him. Every once in a while he will emerge in a huff yelling, “Dad! Dad! Look!” and show me a page in a book that he’s looking at and tell me a story about it. He’ll laugh and run away again.

One night a thunderstorm rumbled outside. The loud bangs and the falling rain against the air conditioner in his window scared my son. He crawled under a blanket and covered his face and body so that the thunder couldn’t hurt him. We opened Where the Wild Things Are and read.

“The book that children have reacted to most strongly, though, is Where the Wild Things Are. They wear out copies at libraries and keep rereading it at home. Some have sent me drawings of their own wild things, and they make mine look like cuddly fuzzball…” Sendak told Hentoff in 1966. “Adults who are troubled by it forget that Max is having a fine time. He’s in control. And by getting his anger at his mother discharged against the Wild Things he’s able to come back to the real world at peace with himself. I think Max is my truest creation. Like all kids, he believes in a world where a child can skip from fantasy to reality in the conviction that both exist.”

The world kids live in is the same as adults but… different. Their experiences are firsts. They have imaginations that haven’t been torn from them. My son can lose hours of his day in a different place. What makes that place feel real to them is that it’s alive and connected to the one with us in it. It’s why Max’s room slowly transforms into a jungle rather than in an instant.

The thunderstorm ended as quickly as it arrived, but my son wouldn’t let it go. He couldn’t sleep. An hour passed. I rubbed his back, tucked him in and put on his favorite sleep-time music. Nothing worked. I sat next to him and listened to his breathing. The thunder would come for him, he thought. He needed to hide. I built him a small fort on one end of his bed. I tucked him under it. Like Max, his imagination had taken over.

“[Max] will fantasize again, but the hope is that like other children, he’ll keep coming back to his mother,” Sendeck said. “So the book doesn’t say that life is constant anxiety. It simply says that life has anxiety in it.”

Life has anxiety “in it” feels right. Life isn’t anxiety. It’s something we create, even if we can’t help ourselves. Sometimes the only way to get away from the feeling is to drift off into another place and come home. Sometimes it’s about finding a world where the Wild Things live and becoming the king of all the stuff that scares you before returning home to find a hot dinner waiting. Sometimes we need books to take us to that place, to show us the way or free us from the burdens of our world and experience.

I told my son it would be ok. I asked him if he would be ok. He told me “yes.” He had a new place to feel safe. The thunder couldn’t get him now in his a fort. He would return when he was ready. He knows he’s loved. He knew everything was alright, eventually.