He listened to his wife’s breath even into snores and wondered how he had arrived here. Drunk, lonely, stewing in his failure. Triumph had been assured. Somehow, he’d frittered his potential away. A sin. Thirty and still a nothing. Kills you slowly, failure. As Sallie would have said, he done been bled out.

[Perhaps we love him more like this; humbled.]

Tonight, he understood his mother, burying herself alive in her beach house. No more risking the hurt that came from contact with others. He listened to the dark beat under his thoughts, which he had had forever, since his father had died. Release. A fuselage could fall from a plane and pin him into the earth. One f lick of a switch in his brain would power him down. Blessed relief at last, it would be. Aneurysms ran in the family. His father’s had been so sudden, forty-six, too young; and all Lotto wanted was to close his eyes and find his father there, to put his head on his father’s chest and smell him and hear the warm thumpings of his heart. Was that so much to ask? He’d had one parent who’d loved him. Mathilde had given him enough but he’d ground her down. Her hot faith had cooled. She’d averted her face. She was disappointed in him. Oh, man, he was losing her, and if he lost her, if she left him—the leather valise in her hand, her thin back unturning—he might as well be dead.

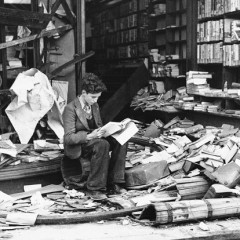

Lotto was weeping; he could tell from the cold on his face. He tried to keep quiet. Mathilde needed sleep. She had been working sixteen-hour days, six days a week, kept them fed and housed. He brought nothing to their marriage, only disappointment and dirty laundry. He fished out the laptop he’d stored under the couch when Mathilde had ordered him to clean up before everyone had come over tonight. He just wanted the Internet, the other sad souls of the world, but instead, he opened a blank document, shut his eyes, thought of what he’d lost. Home state, mother, that light he’d once lit in strangers, in his wife. His father. Everyone had underestimated Gawain because he was quiet and unlettered, but only he had understood the value of the water under the scrubby family land, had captured and sold it. Lotto thought of the photos of his mother when she was young, once a mermaid, the tail rolled like a stocking over her legs, undulating in the cold springs. He remembered his own small hand immersed in the source, the bones freezing past the point of numbness, how he’d loved that pain.

Pain! Swords of morning light in his eyes.

Mathilde was haloed blindingly in the icicles in the window. She was in her slattern’s robe. Her feet were red at the knuckles with cold. And her face—what was it? There was something wrong. Eyes puffed and red. What had Lotto done? Surely something awful. Maybe he’d left porn on his laptop and she’d seen it when she had woken up. Maybe a terrible kind of porn, the worst, maybe he’d been led into it by wild curiosity, clicking through wormholes so progressively more evil that he ended up at the unforgivable. She would leave him. He’d be finished. Fat and alone and a failure, not even worth the air he’d breathe. “Don’t leave me,” he said. “I’ll be better.”

She looked up, then stood and came across the rug to the couch and put the computer down on the coffee table and took his cheeks in her cold hands.

Her robe parted, revealing her thighs, like sweet pink putti. Practically bearing wings.

“Oh, Lotto,” Mathilde said, and her coffee breath mingled with his own dead muskrat breath, and he felt the swoop of her eyelashes on his temple. “Baby, you’ve done it,” she said.

“What?” he said.

“It’s so good. I don’t know why I was so surprised, of course you’re brilliant. It’s just been a struggle for so long.”

“Thank you,” he said. “I’m sorry. What’s happening?”

“I don’t know! A play, I think. Called The Springs. You started it at 1:47 last night. I can’t freaking believe you wrote all that in five hours. It needs a third act. Some editing. I’ve already started. You can’t spell, but we knew that.”

It snapped back to him, his writing last night. Some deep-buried acorn of emotion, something about his father. Oh.

“All along,” she said, “hiding here in plain sight. Your true talent.”

She had straddled him, was easing his jeans down his hips.

“My true talent,” he said slowly. “Was hiding.”

“Your genius. Your new life,” she said. “You were meant to be a playwright, my love. Thank fucking god we figured that out.”

“We figured that out,” he said. As if stepping out of a fog: a little boy, a grown man. Characters who were him but also not, Lotto transformed by the omniscient view. A shock of energy as he looked on them in the morning. There was life in these figures. He was suddenly hungry to return to that world, to live in it for a while longer.

But his wife was saying, “Hello there, Sir Lancelot, you doughty fellow. Come out and joust.” And what a beautiful way to fully awaken, his wife astraddle, whispering to his newly knighted peen, warming him with her breath, telling him he’s a what? A genius. Lotto had long known it in his bones. Since he was a tiny boy, shouting on a chair, making grown men grow pink and weep. But how nice to get such confirmation, and in such a format, too. Under the golden ceiling, under the golden wife. All right, then. He could be a playwright.

He watched as the Lotto he thought he had been stood up in his greasepaint and jerkin, his doublet sweated through, panting, the roar inside him going external as the audience rose in ovation. Ghostly out of his body he went, giving an elaborate bow, passing for good through the closed door of the apartment.

There should have been nothing left. And yet, some kind of Lotto remained. A separate him, a new one, below his wife, who was sliding her face up his stomach, pushing the string of her thong to one side, enveloping him. His hands were opening her robe to show her breasts like nestlings, her chin tipped up toward their vaguely reflected bodies. She was saying, “Oh god,” her fists coming down hard on his chest, saying, “Now you’re Lancelot. No more Lotto. Lotto’s a child’s name, and you’re no child. You’re a genius fucking playwright, Lancelot Satterwhite. We will make this happen.”

If it meant his wife smiling through her blond lashes at him again, his wife posting atop him like a prize equestrienne, he could change. He could become what she wanted. No longer failed actor. Potential playwright. There rose a feeling in him as if he’d discovered a window in a lightless closet locked behind him. And still a sort of pain, a loss. He closed his eyes against it and moved in the dark toward what, just now, only Mathilde could see so clearly.

From FATES AND FURIES. Used with permission of Riverhead. Copyright © 2015 by Lauren Groff.