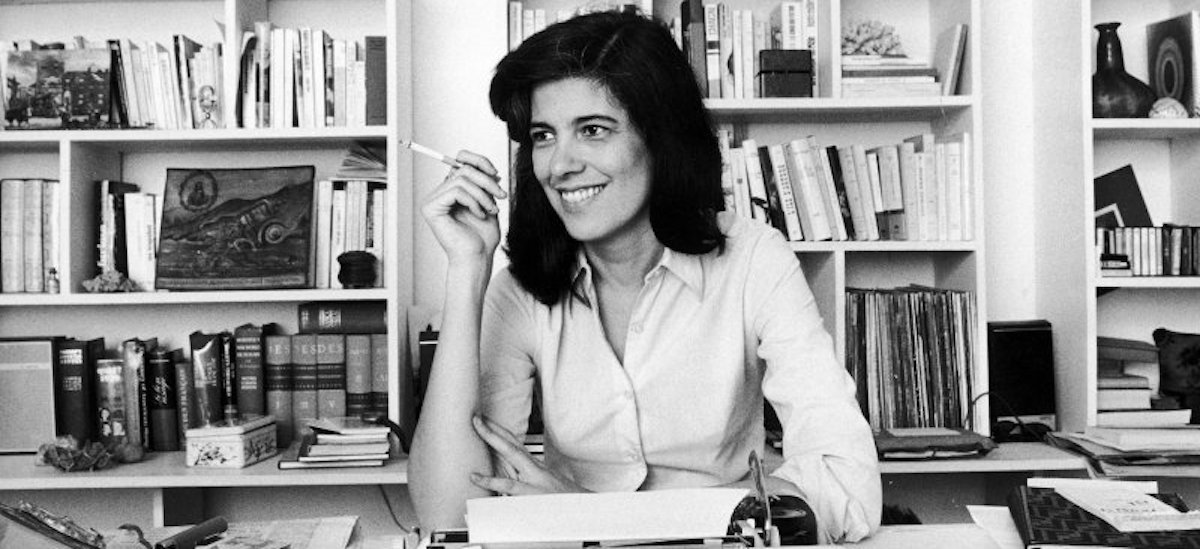

There are plenty of American intellectuals of the 20th century whose absence would have rendered our cultural life much the poorer. But I can think of only two such persons whose absence would have left it duller: Gore Vidal and Susan Sontag. Both were globe-trotting cosmopolites whom the camera loved and vice-versa, and who brought that rarest of qualities to the higher mental life: glamour. (Norman Mailer made things interesting, but glamour was not his métier.)

Vidal, who died in 2012, and his work are currently in eclipse for complicated reasons, a situation that may or may not reverse itself. But Sontag, who died in 2004, remains very much front of mind to the thinking class, one example being the recent exhibit “Camp” at the Metropolitan Museum, which was essentially a slide show meant to illustrate her most famous essay, “Notes on Camp” from 1964. With the publication of Benjamin Moser’s weighty, fully authorized and emphatically titled Sontag: Her Life and Work, she is once again set to take center stage, a place she was apparently aiming for while the other kids in class were seeing Spot run.

Since, as Oscar Wilde quipped, “it is only the shallow people who do not judge by appearances” (one of the two epigraphs to Sontag’s breakthrough first essay collection, Against Interpretation), let’s begin with the packaging of the biography. Its cover is devoid of type and consists simply of a striking black-and-white photo of Sontag circa 1978 by Richard Avedon, gazing out at the viewer with the cool clear eyes of a seeker of wisdom and truth. She is garbed in a gray turtleneck and a sleek and stylish black leather coat. (“The color is black, the material is leather, the seduction is beauty . . .” as the famous closing line of “Fascinating Fascism” has it.) The photo exudes an air of downtown glam, intellectual swagger, unshakeable confidence, and a certain disdain.

Clearly Ecco has calculated that the iconic Sontag image alone will be sufficient to attract the customer base—the exact size of which is an interesting question. Sontag will certainly be the hate-read of the season for Commentary subscribers (she worked there pre-celebrity as a sub-editor), but its publication will put to the test the proposition that in death as in life her fame or notoriety exceeded her actual readership.

A challenging person, Sontag—on the page, in her private and her public life, in retrospect, and for any biographer. For the most part Benjamin Moser has met those challenges to produce an account of “Her Life and Work” that satisfies on multiple levels. I may have a keener interest in Sontag than most—more on that later—but I found myself eager to get back to this 800-plus page doorstop, consistently absorbed by the story it has to tell and impressed by Moser’s acute critical judgments on the works it assesses. Sontag certainly merits the boilerplate adjective that publishers apply to this kind of biography: definitive.

For starters, Moser has clearly put in a heroic amount of work. He claims, and I believe, that he read every word of the thousands of pages of her notebooks, access to which is carefully controlled by the librarians of UCLA. (“Sontag” and “control” are synonymous, as we shall see.) The vast extent of these private writings surprised this reader, who remembers Sontag once testifying to her agonies of composition (you could read her complete published works in three or four days at most). The acknowledgements run to 240 names of acolytes, assistants, admirers, acquaintances and adversaries (e.g., Edmund White and Norman Podhoretz), not counting, resonant phrase, “those who wish to remain anonymous.” (The animus of the Sontag faithful—and possibly ever hers from the grave—is apparently still to be feared.)

Moser has come back with the goods, leaving almost no serious or frivolous or prurient question unanswered. The admirable, the questionable, the deeply contradictory and even perverse, and the sometimes unattractive sides of his subject are on full display. As are many of the most contentious and consequential literary and cultural and political episodes of the past half century.

He is an excellent reader of Sontag’s work and is intellectually up to speed on the forbidding figures and subjects that were her specialty. And there’s enough gossip and catty commentary—from and about the great and the good—to get you through the next six months of cocktail parties. Really, you should read it.

*

It is an interesting thought experiment to consider whether someone going by a name with, in Moser’s excellent phrases, “the gawky syllables” of Susan Lee Rosenblatt would have enjoyed even half the success of a person “with the sleek trochees” of Susan Sontag. Probably not.

She was born in New York City on January 16th, 1933, the daughter of Jack Rosenblatt, who lived an exotic and peripatetic life in the China fur trade, and his wife Mildred Jacobson, a vain and attractive woman who traveled to China with him and helped to run the prosperous Kung Chen Fur Corporation. When Sontag was five, however, her father died of tuberculosis in Tientsien in 1938, leaving a large parental hole to be filled with imagination more than facts.

What followed for Susan and her younger sister Judith (who is one of Moser’s most informative and eloquent witnesses) was an itinerant life—New Jersey, Long Island, Miami, the cultural desert of Tucson, and eventually Los Angeles. Mildred was a neglectful mother at best who succumbed to a lifelong alcoholism and who took up with a series of “uncles.” One of them she met in Tucson and married in 1945, Nat Sontag, a blandly handsome and probably impotent World War II veteran. Sontag’s emotional connection to her stepfather was nonexistent, but she took his name, in part to avoid the anti-Semitic taunting she had experienced at school, but also as an act of reinvention—a decisive step in her transformation from the despised Sue Rosenblatt to that icon of intellectual stardom Susan Sontag. From her earliest years she determined that she was going to hit escape velocity from a drab American reality she referred to as Lower Slobbovia and, as she once described it, “that long prison sentence, my childhood.”

If there is a Rosebud key to Sontag’s life, it is surely her fraught relationship with her mother, a lifelong psychological drama of aching mutual need. An alcoholic whom her daughter Judith terms “the queen of denial,” Mildred alternately bewitched Susan, smothered her emotionally, and pushed her away. Moser sees in this pattern the template for “a sadomasochistic dynamic” apparent in Sontag’s romantic relationships. He makes good use of some Hazelden-ish insights into the behavior of adult children of alcoholics—the self-punishing perfectionism, the low self-esteem, the constant need to compensate for the failings of others, the appetite for control in the face of impending chaos, all qualities to be found on most pages of her notebooks—that still startle a bit when applied to an haute subject who would have reflexively despised them. Late into her life Sontag’s friends would testify to her thralldom to her mother’s neediness and her ability to push her emotional buttons. (Alice Miller’s cult classic for wounded intellectuals, The Drama of the Gifted Child, would have served equally well as an explanatory template.)

If she was difficult, the difficulty inhered in the things she was writing about, not in her writing per se. Hers was a summons to the strenuous life, intellectual division.Like many a lonely child, Sontag was a voracious reader from an early age and a truly champion student. In Tucson a perceptive teacher in her junior high school gave her a copy of The Sorrows of Young Werther to read, and she discovered copies of the highbrow Modern Library editions that she battened onto at the back of a stationery store. Later at North Hollywood High, she would drop the names of Schopenhauer, Freud and Nietzsche in her papers and got caught (and this is a first and surely a last in the history of American pedagogy) reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason hidden behind the copy of Reader’s Digest she was supposed to be reading. Intellectually speaking she was in every way a prodigy who was going places—the right places—fast.

The ultimate dream destination for her was to be in New York and the Partisan Review, which symbolized everything she aspired to. One of her first stops, though, was the Pacific Palisades residence of the literary god Thomas Mann, where, as described in her magical if unreliable memoir Pilgrimage, she was received graciously with two of her fellow students. Sontag had read The Magic Mountain and “all of Europe fell into my head,” a once common phenomenon among the literarily inclined, myself included during college. Pilgrimage is so charming and meaningful to me that I was irrationally disappointed to learn of its wayward fidelity to the actual facts of the visit.

At the startling age of 15 Sontag enrolled for a year at Berkeley, where she read Doctor Faustus and was initiated into adult passion and the lesbian underground by the older and far more sophisticated Harriet Sohmers. The affair would continue off and on for the next decade. “Sexually it was a dud,” the relentlessly candid and refreshing Sohmers testifies; she would seem to have been one of the few persons on the planet to have held a lifetime upper hand with Sontag.

The next year, 1950, Sontag transferred to the University of Chicago, which its young president Robert Maynard Hutchins had transformed into the most demanding and exciting institution of higher learning in the country, and which she had already determined to attend at age 13. Even among the cadre of underaged overachievers that Hutchins had recruited, Sontag stood out for her brilliance and her beauty. One person who was definitely attracted was a sociology professor 11 years her senior, Philip Rieff, 28 to her 17. She attended his lecture; a week later he proposed; six weeks later they were married by a justice of the peace in Los Angeles, celebrating at a Big Boy hamburger restaurant in Glendale. Today Rieff might be arrested for such behavior.

The marriage was an utter disaster. Sontag was in flight from her lesbianism, and furthermore Rieff proved so dull and pedantic that it led to one of the most brutal putdowns in the history of American marriage: Sontag’s realization that “I had married Mr. Casaubon.” Nevertheless she persisted, following Rieff on a wanderjahr through various academic institutions, picking up her degrees on the fly, and offering him invaluable and even heroic assistance in the composition of his brilliant first book, Freud: The Mind of a Moralist. Did she actually ghostwrite it? We’ll revisit this question later.

In 1952 their only son David Rosenblatt Rieff was born. Sontag was so oblivious of the bare facts of pregnancy that she never consulted a doctor and was shocked and puzzled by her labor pains. She would prove to be no better a mother than her own, which hardly surprises. When the marriage fell apart a custody battle ensued that was so bitter it spilled over into the tabloids. Sontag, having read Patricia Highsmith’s underground lesbian classic The Price of Salt, was terrified—with reason—that her romantic history would be used in court to take David away; in the end joint custody was awarded.

David Rieff had, to put it mildly, a difficult growing up, spending large amounts of time in the care of others (or no one) while his mother attended to the all-consuming project of becoming Susan Sontag. It is a small miracle that he turned out so well after much difficulty, today being a highly respected authority on international issues.

By the early 1960s Sontag was teaching at Columbia and making the contacts that would be the springboard for her rise. One was the publisher Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, along with Knopf one of the two most prestigious literary publishers in the country. He knew star power when he saw it and would publish in 1964 her not much-loved first novel The Benefactor (gloomy, echt-European, serious to a fault) and all her subsequent work. Another was William Phillips of Partisan Review, the house organ of New York intellectual life, the magazine she had dreamed of publishing in back in Los Angeles. In 1964, against the objections of his co-editor Philip Rahv, who despised it—and Sontag—Phillips got Partisan Review to publish “Notes on Camp.”

The effect that piece had on Sontag’s career and on American culture was nothing short of astonishing. A challenging essay on the styles and tastes of a marginal and widely hated subculture, in a magazine with a circulation in the mere thousands, went viral without the benefit of social media. Time and the New York Times Magazine, which had vast influence among the chattering classes at the time, took note, and suddenly its author (whose picture, let it be noted, was catnip to photo editors) was famous. And also notorious, somehow being perceived as a threat to all that highbrow culture held dear. The publication of her piece was one of the key inflection points of the 1960s and, in the long run, American culture. And Susan Sontag went on to become Susan Sontag, intellectual icon, whose subsequent books and essays are now an inextricable part of American intellectual history.

*

No consideration of Susan Sontag’s life would be complete without acknowledging that she was one of the great beauties of the 20th century (and a hell of a lot more interesting to talk to than her competitor in that category, Greta Garbo, with whom she was obsessed). This led to an impressively hectic sex life crowded with enough celebrity bedmates to rival Marilyn Monroe’s. Here is just a partial roll call of her short-term and longer-term lovers: Warren Beatty (he’s so vain and he called a lot); Robert F. Kennedy (!); politico Richard Godwin (he brought her to her first heterosexual orgasm, but she ungratefully called him the ugliest man she ever slept with); Jasper Johns (they surely got off on each other’s fame and cultural authority; he dropped her for another woman on New Year’s Eve); dancer and downtown siren Lucinda Childs (on whom I had a distant crush in the 70s); avant-garde playwright Maria Irene Fornes (about whom the hilarious Harriet Sohmers said that “she could make a rock come,” and she would know); Kirk Douglas (Sontag confided that he was very good in bed); Nobelist, Russian émigré dissident and intellectual conscience Joseph Brodsky; her prestigious Daddy Warbucks publisher Roger Straus; and in the last years of her life, the star photographer of rock stars Annie Liebovitz (she apparently slept with every subject she shot for Rolling Stone, from Mick Jagger on down). Moser manages to be richly informative on these matters, suggesting that for all the star power between the sheets, Sontag experienced sex as an occasion for more anxiety than ecstasy; control being a paramount category in her psychic and intellectual life—this is not hard to credit.

Sontag’s talent to explicate and illuminate was equal to her talent to annoy. Few intellectuals have contradicted themselves so blithely, and her positions are generally couched less in statements than in pronunciamentos. (“The white race is the cancer of history” being perhaps the most inflammatory example.) It is striking how many of her marquee moments generated controversy, some of it deeply bitter. To cite just some examples:

“Notes on Camp“ and the collection in which it appeared, Against Interpretation, generated a fair amount of critical pushback from the start. Both were taken by such diverse critics as Hilton Kramer and Irving Howe to be attacks on the discriminations that undergird high culture in favor of a chic and coded style of art and life. Over time some gay critics would take her to task for using their subculture, towards which, in fact, she was not entirely complimentary, as a vehicle for her own advancement; such critiques became more forceful as Sontag’s refusal to identify as gay became an ever touchier issue.

“Fascinating Fascism,” her lethally effective 1975 takedown of filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl for the assiduous way she and her admirers had ignored or covered up her Nazi propensities and past, was an exhilarating and deeply necessary piece: her book Illness as Metaphor, which has done so many thousands of cancer sufferers so much psychic good, aside, the essay was Sontag’s finest hour. But the brutally direct forensics of the piece, applied to one of the few prominent women directors alive, got many writers’ backs up, most prominently Adrienne Rich, who bridled at Sontag’s suggestion that the revival of Riefenstahl’s reputation was a feminist project. It was just one example of the vexed relationship Sontag had with feminism, as a result of her reluctance to call herself a feminist or ally herself with feminism’s perceived aims.

On Photography, probably her most brilliant and influential book, was seen by photographers themselves as a hostile takeover of the art and craft of image-making and a baleful moral judgment on them and photography itself. Sentences like these: “Like guns and cars, cameras are fantasy machines whose use is addictive” and “To photograph people is to violate them . . . .” lend credence to that point of view. As a photographer friend of mine said, “I read On Photography and I realized that I was stealing the soul of my subjects and aiming my camera at them as a weapon.” Certainly the book betrays more than a little ingratitude towards those brilliant photographers (Arbus, Avedon, Hujar and Liebovitz among them) who took the portraits that showcased Sontag’s unique allure and that were such key elements in her rise to fame.

At a meeting of left-wing intellectuals at Town Hall in February 1982 in support of Polish Solidarity, under the influence of her lover and political mentor Joseph Brodsky, Sontag rose to declaim that it was the readers of Reader’s Digest rather than The Nation who “would have been better informed about the realities of Communism” and that communism itself was merely and actually “Fascism with a human face.” This provocative statement from someone who, a decade earlier, had visited Hanoi twice, was rich and got her attacked from all sides of the political spectrum for, variously, hypocrisy, treachery and naivete. I remember reading those words at the time and thinking, “Gee, now you tell us?” (Interestingly her words of left apostasy align Sontag with another politically inclined intellectual famed for his physical beauty and love life: Max Eastman, who went from editing The Masses and The Liberator to penning anti-Communist pieces for, yes, Reader’s Digest.)

Those salvos were mild compared to the firestorm of criticism unleashed by her disastrously ill-considered comments in The New Yorker two weeks after the World Trade Center attacks. Sontag felt it her right and duty to lecture her heartsore fellow citizens about “[t]he disconnect between last Tuesday’s monstrous dose of reality and the self-righteous drivel being peddled by public figures and TV commentators,” and the actual courage of the hijackers rather than their cowardice, in contrast to American bomber pilots “who kill from beyond the range of retaliation,” high in the sky. (Her editors really should have saved her from putting all that into print.) Nothing she says in those three paragraphs about “the sanctimonious, reality-concealing rhetoric” being peddled and the need for “A few shreds of historical awareness” as a corrective was wrong and much of it in fact would prove far-seeing. But her timing and her tone were as badly off and as unkind and misjudged as anything she ever wrote.

However, as always, people were paying attention.

*

I do have a serious bone to pick with Benjamin Moser, and a biographical story to tell that may offer some perspective.

The bone is this: Throughout his book he maintains that Sontag not only provided extensive and invaluable editorial help to her then-husband Philip Rieff on his brilliant first book Freud: The Mind of a Moralist, he goes further than that to claim that the book was in fact written by Susan Sontag and is really her first published work. Now the cult of Rieffians is a small one and is shrinking down to a corporal’s guard, but I am a keen admirer of Rieff and I think that this claim is reckless and just plain wrong.

Witnesses to the considerable time Sontag put in on editing the book certainly exist, but the line between editing and rewriting is a fuzzy one, and this is a case where no one can really locate that line. Sontag always regretted, according to Moser, “signing it over to him” (whatever that means), and the fact that my edition of Freud from 1979 contains not a single mention of Sontag’s contribution in its introduction, its two new prefaces and its new epilogue is a serious injustice. Late in life, in fact, Rieff went so far as to call Sontag “the coauthor of this book,” and I can accept that. But I still think the book is really Rieff’s.

I argue this from two angles. The first is style. I defy anybody to sit down with copies of Freud and, say, Against Interpretation, read a few pages of one and then a few pages of the other, and come to the conclusion that they are the product of one writer: Sontag. I’ve done this. The tone and the vocabulary and style of those books differ so radically to my ear that I cannot credit Moser’s assertion. This is intuition, not proof, but I’ve read most of what both of these authors have published and I stand by my opinion.

My second argument is more empirically based: Philip Rieff wrote a book nearly as great as Freud, all by himself, without an iota of help from his ex-wife, published seven years later: The Triumph of the Therapeutic: The Uses of Faith After Freud. This book, a critique of the psychological type brought to the fore in the wake of Freudianism’s triumph, was praised by the likes of Robert Coles, Frederick Crews, and Alasdair MacIntyre, and it served as an inspiration for much of Christopher Lasch’s work, both The Culture of Narcissism and later books. Although Rieff’s tone in this book is more urgent and, let’s say, vatic, there really is no serious falling off in cogency between it and its predecessor. It is, transparently and obviously, the work of the same author who wrote Freud. It is, in fact, a great book and not the “meager fruit” that Moser dismissed Rieff’s later work as. After that, it is true, Rieff became more and more an eccentric but still brilliant crank, a kind of failed early study for Allan Bloom, but I know people who studied with him who would take angry issue with Moser’s claim that he “had something of the scam artist about him.”

Here is the story: Sometime in the mid-90s when I was working at W.W. Norton I got a proposal for a biography of Susan Sontag by the experienced biographers Carl Rollyson and his wife Lisa Paddock. I picked it up in order to glean such new nuggets of information about Sontag as it might contain, but as for publishing an unauthorized biography of such a formidable and still living figure, that was not on my to-do list. Who needed the inevitable headaches? But to my mild surprise I found the proposal to be informed and thorough and penetrating and sympathetic towards its subject, so we signed it up. And that was when the trouble began.

I of course knew that the biography-in-progress would be greeted by Sontag and her circle with distaste and opposition, but I was not prepared for the low viciousness of the campaign against it. The book was characterized as some kind of political hit job on Sontag from the right, which it absolutely was not. The notion that the biographers planned to write candidly about Sontag’s homosexuality, a fact known to just about everybody, was called an unforgivable intrusion on her privacy. Lies were spread about the biographers and their research methods, the most hilarious being from the grandee John Richardson, who claimed that Carl Rollyson threatened him with bad reviews if he, Richardson, did not consent to be interviewed. As if!

The organs of New York intellectual life behaved abominably. Rollyson, with complete legitimacy as a PEN member and a working biographer, sought to see the minutes of the board meetings of PEN American during the years that Sontag was the president of that organization. PEN, of course, preaches total transparency to other organizations and corporations and governments around the globe and its membership includes many biographers of note. In this case, however, the then-president of PEN, Michael Scammell (a biographer of Solzhenitsyn yet!) denied him that access at a stormy meeting at the PEN offices. The hypocrisy of such an action by such an organization was maddening.

Even worse was the behavior of Sontag’s publisher, Roger Straus, who asked the editor in chief of Norton, Starling Lawrence, to cancel the book on the basis of, I suppose, its putative scurrilousness (about which Straus knew nothing except that Sontag objected). When he, quite rightly, declined to do so, Straus retaliated by canceling Lawrence’s contract for a novel to be published by, yes, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

I left Norton for another house before I had a chance to edit the book, Susan Sontag: The Making of an Icon. The University of Texas Press published a revised and updated edition in 2016, and I’ve been reading around in it. I’m prejudiced, of course, but I think it is pretty good. It does not have the amplitude of Moser’s work, nor, of course, the all-important access to Sontag’s notebooks, but for a brisk and coherent account of the person and the institution who was Susan Sontag, I recommend it. It improves on Moser’s biography in one respect: its narrative pacing, as Sontag suffers at times from its stop/start episodic structure and a certain temporal waywardness. Benjamin Moser certainly found it useful, as the book is cited quite a few times in the source notes.

As for me, I had been a board member of PEN for a few years, but sickened by the organization’s behavior in this matter, I never renewed my membership. The whole experience was a very unpretty look into the behavior of some New York intellectuals when one of their own feels threatened. It’s a tight little game they run in this town.

*

A curious thing happened to me as I began re-reading Sontag’s work for the first time in years in order to write this essay.

Susan Sontag incarnates the sort of heroic intellection that has become historical—the product of a particular set of 20th-century circumstances. There was in the long duree of the postwar years an overriding sense of crisis that affected the high art of the west and the intellectuals and historians who sought to grapple with it (see Mark Greif’s superb and original The Age of the Crisis of Man for the full and absorbing story). The locus of this crisis was the European disaster, and Americans, who had of course mounted a rescue mission and emerged with immense power and prestige, felt challenged to rise to the occasion of taking it all in and offering, if not something meliorative, at least something worthy of its dark subject.

Susan Sontag took on this task as her own special mission, measuring herself against the heroes of European culture (Mann, Artaud, Weil, Benjamin, Canetti et al.) and translating their insights into an American idiom. She succeeded to an unprecedented degree almost by force of will, in the process transforming herself into one of the few native-born American intellectuals to gain the unqualified respect of their European counterparts and to be welcomed into their company. All this is what made her so exciting to read; if she was difficult, the difficulty inhered in the things she was writing about, not in her writing per se. Hers was a summons to the strenuous life, intellectual division. Like Nietzsche, she held out the prospect that you too might become a Hyperborean, with a similar effort of the will.

All of this I thrillingly felt as I read Against Interpretation again. Under her spell my perceptions seemed to be quickened, my judgments became sounder, my latent ambition to understand everything renewed. I felt . . . Hyperborean!

And then I departed my Sontagian Arctic to head to a local coffee shop for a mid-morning cortado. You must understand that I was nowhere near Lower Slobbovia. The Snowy Owl is a mildly bohemian and upscale place in a pleasant summer town on Cape Cod. Its vibe is what I’d call alterna-Unitarian. Everyone seems to have a college degree or to be working towards one. But under the Sign of Sontag as I was, everything and everybody suddenly just . . . wouldn’t do. All the once-charming owl imagery seemed now to me like kitsch. Everybody was wearing, you know, shorts. And tee shirts advertising the wrong schools and wrong bands and even, shudder, New England sports teams. The haircuts and tattoos were unfortunate. Walter Benjamin would have taken one look at the place and left.

The word for this frame of mind is snobbery, and I had caught a nasty case of it from Susan Sontag. This is the moral hazard inherent in much of her work. I shook it off and considered the pleasant quotidian reality of the world I was inhabiting. The coffee at the Snowy Owl really is quite good. I sipped my cortado and smiled at a baby.