Our country is in the grips of a gun violence crisis. It has crept into our neighborhoods, towns, cities, and states. It has created fear in spaces of joy and innocence, like movie theaters and schools. It costs our cities and towns millions of dollars and leaves holes in our communities that can never be filled. It makes our country stand out in the worst of ways.

Neither of us began our lives in public service thinking that gun violence prevention would be our life’s work. But gun violence shattered our lives as we knew them, and we won’t stop fighting to prevent mass shooting tragedies and the gun violence that occurs on our streets and in our homes every single day.

Survivors, advocates, and allies can change hearts and minds—and move more people to join our fight for solutions— by telling stories about the irreparable damage that gun violence does to families and communities across the country.

–Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and Captain Mark Kelly

![]()

When I Think of

Tamir Rice While Driving

Reginald Dwayne Betts

in the backseat of my car are my own sons,

still not yet Tamir’s age, already having heard

me warn them against playing with toy pistols,

though my rhetoric is always about what I don’t

like, not what I fear, because sometimes

I think of Tamir Rice & shed tears, the weeping

all another insignificance, all another way to avoid

saying what should be said: the Second Amendment

is a ruthless one, the pomp & constitutional circumstance

that says my arms should be heavy with the weight

of a pistol when forced to confront death like

this: a child, a hidden toy gun, an officer that fires

before his heart beats twice. My two young sons play

in the backseat while the video of Tamir dying

plays in my head, & for everything I do know, the thing

I don’t say is that this should not be the brick and mortar

of poetry, the moment when a black father drives

his black sons to school & the thing in the air is the death

of a black boy that the father cannot mention,

because to mention the death is to invite discussion

of taboo: if you touch my sons the crimson

that touches the concrete must belong, at some point,

to you, the police officer who justifies the echo

of the fired pistol; taboo: the thing that says that justice

is a killer’s body mangled and disrupted by bullets

because his mind would not accept the narrative

of your child’s dignity, of his right to life, of his humanity,

and the crystalline brilliance you saw when your boys first

breathed;

the narrative must invite more than the children bleeding

on crisp fall days; & this is why I hate it all, the people

around me,

the black people who march, the white people who cheer,

the other brown people, Latinos & Asians & all the colors

of humanity

that we erase in this American dance around death, as we

are not permitted to articulate the reasons we might yearn

to see a man die; there is so much that has to disappear

for my mind not to abandon sanity: Tamir for instance,

everything

about him, even as his face, really and truly reminds me

of my own, in the last photo I took before heading off

to a cell, disappears, and all I have stomach for is blood,

and there is a part of me that wishes that it would go away,

the memories, & that I could abandon all talk of making

it right

& justice. But my mind is no sieve & sanity is no elixir &

I am bound

to be haunted by the strength that lets Tamir’s father,

mother, kinfolk resist the temptation to turn everything

they see into a grave & make home the series of cells

that so many of my brothers already call their tomb.

*

Response to “When I Think of Tamir Rice While Driving”

from Samaria Rice, Mother of Tamir Rice

When I think of Tamir as his mother, the woman who gave birth to him, I wonder why my son had to lose his life in such a horrific way in this great place we call America. Police terrorism is real in this country. In many countries this may seem normal, but in America this is not supposed to be normal.

Tamir was an all-American kid with a promising and bright future. Tamir was the life of his family, and I always knew that my son would make some type of change. He was a talented, caring, and loving child. When I lost Tamir, I lost a piece of myself. I was thrown into the political lights and now I am a national leader fighting for human rights.

American police terrorism was created to control the black and brown people of slavery. This remains vivid today. We need change across this country and accountability for our loved ones whose lives have been stolen by American terrorism. Who will govern the government when they continueto murder American citizens? Injustice in this country is pitiful and pathetic. The injustice starts with economics, education, and politicians.

Tamir will always be the reason I continue to do this work and fight for equality of human rights in this country. I am not afraid of the leadership that I have come into upon the death of my son. I am not afraid to create change and to be a part of change.

![]()

22

Brian Clements

The guy my girlfriend ran off with

in 1983 drove a rusted-out Beetle

and carried a .22 pistol for runs to the bank

to drop off nightly deposits from the General

Cinema, where he was Assistant Manager

and where I worked and saw Rocky Horror

about 20 times more than I wanted to

in egg-and-tp-drenched midnight shows.

He lived in a rat-trap, roach-infested, leaning-over

shack on the edge of The Heights,

a few streets over from the house where,

in 2004, a local TV reporter was murdered

in her bed, her face beaten beyond recognition.

—

In 1988, on my first night as Assistant Manager

at a restaurant in Dallas, a fight broke out

between a pimp and a private investigator,

who also may have been a pimp. A group

of frat boys decided to jump in and knocked

the whole scrum over onto the floor

just on the other side of the bar from me.

The pimp came up pointing a .22 semiautomatic

directly at the closest object, which happened

to be my forehead. He didn’t shoot—

just waved his gun around until everyone

cowered under their tables—then

calmly walked out the front door and down the street.

—

My best friend in sixth or seventh grade

moved to Arkansas from New Mexico.

Ron’s skin was lizard-rough.

He raised hamsters and hermit crabs.

I struck him out for the last out of the Little League

Championship. We went out to his father’s farm

and shot cans and bottles with his .22 rifle.

Back in New Mexico, he’d had some health problems

and his mother had shot herself in the head.

A few years ago, a dead body was found

buried on his father’s property. Ron’s son

ended up shooting himself in the head as well.

He was 22.

—

On December 14, 2012, an armed gunman

entered the Sandy Hook School with two pistols,

a Bushmaster .223, hundreds of rounds of ammunition,

and a shotgun in the car. Rather than turn right,

toward my wife’s classroom where she pulled

two kids into her room from the hallway,

he turned to the left, murdered twenty children

and six adults, including the principal

and the school psychologist, both of whom

went into the hallway to stop the gunman,

and shot two other teachers, who survived.

After that, a lot of other things happened,

but it doesn’t really matter what.

*

Response to “22″

from Po Kim Murray,

Cofounder of Newtown Action Alliance

It did not matter to the National Rifle Association (NRA), the Republican members of Congress, Donald Trump, Republican governors, Republican state legislators, and some Democratic leaders that my neighbor killed his mother in her bed, then drove to Sandy Hook Elementary School to brutally gun down twenty children and six educators with an AR-15 with high-capacity magazines, or that a hundred thousand Americans are killed or injured by guns in our towns and cities across the nation every single year, or that there are nearly three hundred mass shooting incidents annually.

It mattered to us. We are a group of Newtown, Connecticut, neighbors and friends who formed the Newtown Action Alliance, a grassroots group advocating for cultural and legislative changes to end gun violence in our nation.

It mattered to 90 percent of Americans who support expanded background checks. It mattered to families of victims and survivors directly impacted by gun violence.

Because it still matters to us, we will work to hold all state and federal elected representatives accountable for standing with the NRA instead of taking action to keep all of us safe from gun violence.

Despite the NRA rhetoric, we know firsthand that guns kill and guns don’t make us safer.

![]()

The Leash

Ada Limón

After the birthing of bombs of forks and fear,

the frantic automatic weapons unleashed,

the spray of bullets into a crowd holding hands,

that brute sky opening in a slate metal maw

that swallows only the unsayable in each of us, what’s

left? Even the hidden nowhere river is poisoned

orange and acidic by a coal mine. How can

you not fear humanity, want to lick the creek

bottom dry to suck the deadly water up into

your own lungs, like venom? Reader, I want to

say, Don’t die. Even when silvery fish after fish

comes back belly up, and the country plummets

into a crepitating crater of hatred, isn’t there still

something singing? The truth is: I don’t know.

But sometimes, I swear I hear it, the wound closing

like a rusted-over garage door, and I can still move

my living limbs into the world without too much

pain, can still marvel at how the dog runs straight

toward the pickup trucks break-necking down

the road, because she thinks she loves them,

because she’s sure, without a doubt, that the loud

roaring things will love her back, her soft small self

alive with desire to share her goddamn enthusiasm,

until I yank the leash back to save her because

I want her to survive forever. Don’t die, I say,

and we decide to walk for a bit longer, starlings

high and fevered above us, winter coming to lay

her cold corpse down upon this little plot of earth.

Perhaps we are always hurtling our body towards

the thing that will obliterate us, begging for love

from the speeding passage of time, and so maybe

like the dog obedient at my heels, we can walk together

peacefully, at least until the next truck comes.

*

Response to “The Leash” from Caren Teves,

Mother of Alex Teves, Killed in the Aurora,

Colorado, Shooting

July 20, 2012, 12:38 a.m.: A 24-year-old white male enters an Aurora Cinemark movie theater through an unalarmed security door. Fueled by a self-admitted desire for infamy and armed with three guns and six thousand rounds of ammunition that he easily and legally obtained, despite his past and current mental health history, he begins shooting with the intent to kill everyone.

In the rear of the theater, another 24-year-old man performs a selfless act of love. Knowing the risk to himself, he immediately pulls his girlfriend to the floor using his body to successfully shield her when he is hit in the forehead with a single armor-piercing bullet, violently ending his life.

My husband, Tom, and I were not surprised by the heroic actions of our first-born son, Alex Teves. He was always kind and fiercely protected those he loved. We miss him every moment of every day. Alex is one of over 30,000 people killed annually with guns in the United States.

The quest for fame is a well-known motivating factor in rampage mass killings. Upon learning this, we founded NoNotoriety.com, calling for responsible media coverage of these killers in an effort to save lives.

![]()

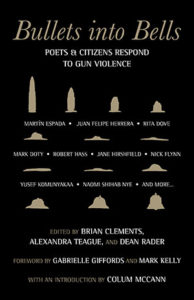

Excerpted from Bullets into Bells: Poets & Citizens Respond to Gun Violence, Edited by Brian Clements, Alexandra Teague, and Dean Rader, with an introduction by Colum McCann and a foreword by Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and Captain Mark Kelly (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with Permission from Beacon Press.