The killers came by streetcar. Their boots struck the packed clay earth like muffled drum beats as they bounded from the cars and began to patrol the wide dirt roads. The men scanned the sidewalks and alleyways for targets. They wore red calico shirts or short red jackets over white butterfly collars. They were working men, with calloused hands and sunburned faces beneath their wide-brimmed hats. Many of them tucked their trousers into their boot tops. A few wore neckties. Each one carried a gun.

Throughout that summer and autumn, white men had been buying shotguns, six-shot pistols, and repeating rifles at hardware stores in Wilmington, North Carolina, a port city set in the low Cape Fear country along the state’s jagged coast. It was 1898, a tumultuous mid-term election year. The city’s white leadership had vowed to remove the city’s multi-racial government by the ballot or the bullet, or both. Few white men in Wilmington intended to back their candidates that November without a firearm within easy reach. There was concern among whites in Wilmington, where they were outnumbered by blacks, that stores would run dry on guns, and that suppliers in the rest of the state and in South Carolina would be unable to meet demand.

Gun sales soared. J.W. Murchison, who operated a hardware store in downtown Wilmington, sold 125 rifles in October and early November alone. That was four or five times his normal sales. These were Colt and Winchester repeating rifles, capable of firing up to 16 rounds in rapid succession. Murchison also sold more than 200 pistols during that same period, and nearly 50 shotguns. Owen F. Love, a smaller hardware dealer, sold 59 guns of all types during October and early November. Murchison and Love were proper white men, which meant they sold firearms only to other white men, and primarily to those who were supporters of the white supremacist Democratic Party. They did not sell to blacks. When pressed on the subject later, Owen Love responded, “I had no objection to selling to any respectable man, white or colored, but I would refuse to sell cartridges, pistols or guns to any disreputable Negro.”

“It is doubtful if there ever was a community in the United States that had as many lethal weapons per capita as in Wilmington at that time,” one of the city’s leading white supremacists wrote years later. This was only a slight exaggeration. Among the city’s whites, there were almost as many guns as men, women and children. Wilmington was the largest city in North Carolina, but the demand for weapons had exhausted the supplies of every gun merchant in town. They telegraphed emergency orders to dealers in Richmond and Baltimore, who loaded guns and bullets on railroad cars headed south.

The armed men emerging from streetcars on that mild, sunny morning of November 10, 1898, had just marched, more than a thousand strong, to the office of a black-run newspaper, the Daily Record. The mob had hoped to lynch the Record’s editor, Alexander Manly, a crusading young newspaperman with as much white blood in his veins as black. Family lore held that Manly was the grandson of a white man, a former North Carolina governor named Charles Manly. People who passed Alex on the street often assumed that he, too, was white. He had fair skin and wavy dark hair brushed back from his forehead, in the style of many white men of the day.

Earlier that summer, Manly wrote an editorial that had pierced the buried insecurities of southern white men. He suggested that most black men lynched for raping white women were, in fact, the women’s consensual lovers. Manly also wrote what everyone in Wilmington, black and white, knew but never acknowledged: Many black men accused of raping white women where themselves products of illicit sex—between white men and slave women. These black men “were not only not ‘black’ and ‘burly’ but were sufficiently attractive for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with them as is very well known to all,” Manly wrote. In fact, he went on, it was black women who bore the brunt of rape–by white men who assaulted them with impunity. After the editorial was published, the young editor was inundated with death threats and advised by friends, both black and white, to flee the city at once.

The city’s thriving population of black professionals contradicted the white portrayal of Wilmington’s blacks as poor, ignorant and illiterate.After the gunmen had marched to the Record office but failed to find Manly there, they heard rumors that black men, in response to white mobs coursing through the streets, were massing at the corner of North 4th and Harnett streets nearby. The intersection lay at the heart of a predominantly black neighborhood known as Brooklyn, thirteen blocks and a short streetcar ride north of the Record office. The men in the mob were inflamed with excitement and eager to fire their weapons. Some had already shot rifles from a streetcar, sending rounds whistling past black homes and small businesses along nearby Castle Street. One of the men carried a U.S. .44 caliber Navy-issue rifle, though he was not a member of the city’s Naval Reserves. Others wielded Army or Navy or police revolvers, belt revolvers or small pocket revolvers. A few of the younger men still owned guns their fathers or uncles had fired during the Civil War. Some veterans called the weapons blueless guns because the dark blue finish had worn off to expose a dull gray color.

The men moved in columns with their weapons raised, in something approaching a military formation. They swept past clapboard houses and muddy yards in a mixed neighborhood of blacks and whites at the edge of Brooklyn. Wilmington was not yet a uniformly segregated city. In fact, some considered it the most integrated city in the South, with blacks and working-class whites living side by side in each of the city’s five wards. But this was still the South. Some Wilmington neighborhoods were largely black, such as the First Ward and most of Brooklyn, or purely white, such as the tidy blocks of tree-lined streets near the Cape Fear.

Around 11 o’clock, a group of whites from the mob arrived to find a crowd of black men gathered across at North 4th and Harnett Streets, outside a popular drinking spot called Brunje’s Saloon. Some of the men were known to whites as “Sprunt n*****s.” They worked as stevedores, laborers, and machine operators at the Sprunt Cotton Compress on the Cape Fear riverfront. They loaded boulder-sized bales of cotton onto merchant ships bound for Europe. The compress was the largest cotton export firm in the country, providing jobs to nearly 800 black men.

Some of the Sprunt workers had abandoned their posts at the compress after hearing rumors that a white mob was burning black homes in Brooklyn and plotting to butcher black men at Sprunt’s. No homes had been burned, and no one had been killed. But the Sprunt workers were convinced that their lives, and the lives of their wives and children, were at risk.

They made their way to Brunje’s Saloon, where they could see packs of white gunmen descending on the packed-clay streets of their neighborhood. The white men were cursing blacks, and the black men bristled. The rising tensions pierced the tranquility of a pleasant fall day, bright and cool, with a gentle river breeze.

*

The white planters, lawyers, and merchants who had dominated Wilmington since its founding in 1739 had lost control of the city during the Civil War and Reconstruction. They did not intend to surrender Wilmington again.

During the war, Wilmington held out longer than any other Confederate seaport. After New Orleans and Norfolk were captured by Union forces in the spring of 1862, and with Charleston under a Union siege for much of the war, Wilmington became the main source of weapons, clothing, food and supplies for the Confederacy. Wilmington’s sleek, swift blockade runners often evaded Union warships that were strung like beads in an armada off the Carolina coast.

Wilmington was protected by Fort Fisher, a Confederate fortress of earth and sand battlements 20 miles south of the city, where the Cape Fear River plunged into the Atlantic. On January 15, 1865, after a punishing siege, Fort Fisher was overrun by Union troops, who continued northward along the river and seized Wilmington one month later. The war did not formally end until General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 9th. But the collapse of the last Confederate sea port at Wilmington was the signal that defeat was inevitable.

The end of the war brought federal occupation and Reconstruction, which tore at the foundation of white supremacy in Wilmington. Former slaves were promised the protection of three new Reconstruction era amendments. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in December 1865, abolished slavery. The Fourteenth, adopted in July 1868, granted citizenship to former slaves born in the United States and guaranteed equal protection under the law. The Fifteenth, ratified in February 1870, guaranteed black men the unrestricted right to vote. The newly promised rights prompted freedmen to make their way to Wilmington and other burgeoning cities across the South in search of work. By 1880, Wilmington would boast the highest percentage of black residents of any large Southern city–60 percent, compared to 44 percent in Atlanta, 27 percent in New Orleans and 17 percent in Louisville.

But during the mid-1870s, North Carolina’s white supremacists, calling themselves Redeemers, reasserted control. They unleashed night-riding Ku Klux Klansmen who whipped and murdered blacks and burned their homes, schools and churches. They warned white voters that black men would steal their jobs and rape their women. They imposed restrictions that reduced freedmen to near-slave status. Well before in the close of Reconstruction in 1877, the vengeance of the Redeemers had essentially suspended the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments in North Carolina. White supremacy was triumphant

During the early 1890s, a new political reality emerged. White farmers in the Populist Party, driven to ruin by collapsing farm prices during a devastating recession, rebelled against the bankers and railroad men who dominated the state’s white supremacist Democratic Party. They teamed with Republicans, white and black, in an uneasy alliance known as Fusion. By 1898, Fusionists had won control of the state legislature and of city and county governments in Wilmington, which was now 56 percent black. In a city of some 20,000 people, there were 3,000 fewer whites than blacks.

Among the political spoils of the Fusionist victory were appointments of black men to low-level positions. Hundreds of these black functionaries were scattered across the region known as the Black Belt, the 16 eastern North Carolina counties with black majorities. Black men were also elected to the state legislature and to political office in Wilmington, reclaiming positions they had held during Reconstruction. A black politician represented New Hanover County, which included Wilmington, in the state House of Representatives. Another black man, George Henry White, was elected to the United States House of Representative—the only black man in Congress. White served North Carolina’s heavily black 2nd District in the eastern part of the state, known as the Black Second.

In Wilmington, three of the city’s 10 aldermen were black, as were 10 of 26 city policemen. There were black health inspectors, a black superintendent of streets and far too many—for white sensitivities—black postmasters and magistrates. White men could be arrested by black policemen and, in some cases, were even obliged to appear before a black magistrate in court.

In 1898, a field representative for the American Baptist Publication Society called Wilmington “the freest town for a negro in the country.” Blacks merchants sold goods from stalls at the city’s public market—a rarity for a southern town at the time. Black men delivered mail to homes at times of day when white women were unattended. They sorted mail beside white female clerks.

A black barber served as county coroner. The county jailer was black, and the fact that he carried keys to the lockup infuriated whites. The county treasurer was a black man who distributed pay to county employees, forcing whites to accept money from black hands. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison had appointed a black man, John C. Dancy, as federal customs collector for the port of Wilmington. Dancy had replaced a white supremacist Democrat, and he drew an astonishing federal salary—$4,000 a year, or $1,000 more than the governor earned. A white newspaper editor ridiculed Dancy as “Sambo of the Custom House.”

In Wilmington, black businessmen pooled their money to form two small banks that loaned cash to blacks starting small businesses. Several black professionals ran small law firms and doctor’s offices, serving clients and patients of their own race. A black alderman from Raleigh, the capital, noted with some surprise that certain black men in Wilmington had built finely appointed homes with lace curtains, plush carpets, pianos and even, he claimed, servants. The city’s thriving population of black professionals contradicted the white portrayal of Wilmington’s blacks as poor, ignorant and illiterate. In fact, Wilmington’s blacks had higher literacy rates than any other blacks in North Carolina, a state in which nearly a quarter of whites were illiterate.

For white politicians and newspaper editors, this was an intolerable. They warned of “Negro Rule,” though black men held only a fraction of elected and appointed positions in the city and the state. They predicted that if blacks continued to vote and hold office, black men would feel empowered to rape white women and seize white jobs. Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell, a former Confederate officer who led the white gunmen into Brooklyn on November 10th, complained, “N***** lawyers are sassing white men in courts; n***** root doctors are crowding white physicians out of business.”

There were foreboding newspaper headlines:

MORE NEGRO SCOUNDRELISM

MORE NEGRO INSOLENCE

NEGRO CONTROL IN WILMINGTON

IS A RACE CLASH UNAVOIDABLE?

With a November mid-term election looming, the state’s Democratic politicians launched a White Supremacy Campaign in the spring of 1898. It was designed to evict blacks from office and intimidate black voters from going to the polls. But first, it was necessary not only to terrify black families, but also to convince white men everywhere that merely voting in November was not enough. Whites had to be persuaded that free blacks posed an imminent threat to their privileged way of life. And they were told, every day, in newspapers and at campaign rallies next to cotton farms and tobacco fields, that the only way to eliminate that threat forever was for the good white men of Carolina to bring out their guns.

White newspapers printed false stories of black men lusting after white women, insulting white men and plotting “Negro domination.” They published drawings of Zip Coon, a predatory, thick-lipped character who embodied, for whites, the insolence and duplicity of all blacks. Wilmington was declared a white man’s city, and white citizens were ordered to defend it. A popular song, belted out at bonfire rallies by white men bearing Winchesters, contained the affirming verse, “Rise, ye sons of Carolina! Proud Caucasians, one and all.”

As the White Supremacy Campaign gained momentum, the state Democratic Party published a tidy little pamphlet titled the Democratic Handbook. It was distributed to thousands of white voters, with instructions to vote “the white man’s ticket.” A single sentence in the handbook distilled the party’s all-consuming objective: “This is white man’s country and white men must control and govern it.”

On Election Day, November 8th, 1898, gangs of white men threatened and intimidated black men attempting to vote. Only a fraction of registered blacks managed to cast ballots. Packs of white men overran polling places and stuffed ballot boxes with phony ballots. The result was a Democratic sweep of local races for statewide offices. But because municipal elections were not scheduled until the following March, city government remained under the control of Fusionists, both black and white.

White supremacist leaders chose not to wait until that March, four months away. They sent white gunmen into streets on November 10th, 1898, two days after the election, to restore Wilmington to its natural order. Their actions that day would rob blacks of the rights they had won during the Civil War and Reconstruction. They would destroy Wilmington’s thriving black middle-class and drive out so many black families that Wilmington once became a white-majority city. And they would instill a virulent form of white supremacy that suppressed black voting rights and civil rights well into the second half of the 20th century.

*

Across the street from Brujne’s saloon late in the morning on November 10th, white men gathered in a tight knot, cursing and shouting racial slurs at the black workers milling across the street. The whites hollered for the blacks to disperse, which only offended and aroused them. A city newspaper reported that the black men were “in a bad temper.” They stood their ground, anxiously eyeing the growing cluster of armed white men on the opposite corner. As the two sides exchanged more curses and taunts, one of the white men shouted out the mob’s purpose: They were “going gunning for n*****s,” he said.

A black man named Norman Lindsay tried to calm his neighbors. He told them that their families were in danger of being burned out and shot dead if they continued to antagonize the white men.

“For the sake of your lives, your families, your children, and your country, go home and stay there. I’m as brave as any of you, but we are powerless,” Lindsey told them in a defeated tone.

The men argued with him. They insisted that they had every right, as citizens and residents of their neighborhood, to gather where they pleased, particularly with their families under threat from a mob seemingly bent on murder.

Aaron Lockamy, a white police officer, decided to offer his services as a mediator. Lockamy did not look or act like a police officer. He was a middle-aged man, deliberative and tentative. And even at age 58, he was not an experienced cop. He had served only on occasional part-time duty before he was deputized earlier that month as a full-time officer in anticipation of election trouble.

Lockamy wore his police badge prominently on his chest that morning. He had been stationed in Brooklyn to monitor the opening at 8 o’clock of two saloons elsewhere on North 4th Street after they had been ordered shut for two days for the election. He had been instructed by the city’s white police chief not to arrest anyone, black or white. He was simply to keep an eye on the saloons. Negotiation was not part of his job, but Lockamy believed he could appeal to the more reasonable men among the two camps in the showdown near the saloon.

He had walked about a block when he heard a sharp volley of gunfire from the crowded corner at North 4th and Harnett. He turned to see two black men fall dead in the street.When Lockamy appeared at the corner of Harnett and North Fourth Street, looking hesitant, he was summoned by several white men gathered there. They asked him, not very politely, considering that he was a fellow white man, to move the black men off the corner. Lockamy sighed. He walked over to the men. They seemed wary and defensive. They did not appear to be carrying weapons, at least not openly.

Lockamy persuaded them to move a short distance to the opposite corner, by W.A. Walker’s grocery store, a frame structure with low tilted roof that shaded a wooden slat walkway. This provided a slightly better opportunity for them to gauge the intentions of the white mob. The whites responded by moving to a more protected position just down the street from Brunje’s Saloon, near the white steeple of St. Matthew’s Evangelical Lutheran Church.

The black men’s new position did not satisfy all the white men. Several of them summoned officer Lockamy again. They dispatched him once more to try to move the black men. Again, the blacks rebuffed him and continued to hold their ground. Lockamy trudged back to the white men. They demanded to know what the blacks had told him. “They told me that I might go to hell, or where I pleased,” Lockamy said evenly. “They were not going anywhere. They did not need me over there, no how.’’

The white men were through with Lockamy. They told him they would move those Negroes themselves. Lockamy gave up trying to negotiate. He decided to return to his original mission of watching the two saloons further west on North 4th Street. He had walked about a block when he heard a sharp volley of gunfire from the crowded corner at North 4th and Harnett. He turned to see two black men fall dead in the street.

*

Ten blocks away stood the Wilmington Light Infantry armory, a two-story Greek revival building of pale white marble and pressed brick that towered over Market Street. Billeted inside were a hundred and six well-drilled Light Infantry soldiers who had recently returned from federal duty in the Spanish-American War. The Light Infantry was part of the state’s militia system. It was supposed to report to the state adjutant general and thus, ultimately, to North Carolina’s Republican governor in Raleigh. But the Infantry effectively served as the private militia of Wilmington’s white supremacists, many of them related by blood or marriage. An appointment to the Light Infantry was a symbol of achievement and social standing. Prospective members had to be approved by current members, insuring that the Light Infantry remained a closed club for upper-class and middle-class whites wedded to white supremacy.

Earlier that summer, the city’s white merchants worried that the Light Infantry lacked the firepower to properly intimidate and control Wilmington’s black majority. They raised $1,200 to purchase a rapid-fire Colt gun for the unit. It was a relatively new weapon, developed just nine years earlier. Under optimum conditions, the air-cooled gun could fire up to 420 rounds in extended bursts without overheating the barrel.

Nearby, another militia, the Naval Reserves, was also ready and waiting on the morning of November 10th. The Naval Reserves, formally known as the North Carolina Naval Militia, was a more egalitarian unit than the Wilmington Light Infantry. While men from the gentry dominated the Naval Reserves’ upper ranks, middle class and working-class men were permitted to join. Most were from Democratic families active in the White Supremacy Campaign. Like the men of the Light Infantry, members of the Naval Reserves had served on federal duty during the Spanish-American War, aboard the USS Nantucket off South Carolina. They, too, returned to Wilmington late that summer. And they, too, ostensibly reported to the governor but served instead as a white supremacist militia.

Two days before the gunshots rang out on North Fourth Street, the Naval Reserves had been supplied with its own rapid-fire gun–a Hotchkiss gun that could fire 80 to 100 rounds a minute. The gun’s bore was three-quarters of an inch. Its effective range was five miles. At three miles, the steel rounds were said to be able to penetrate a thick steel plate. One of Wilmington’s white newspapers called it “a very destructive piece of ordnance.”

Just before mid-day on November 10th, reports of gunfire at North Fourth and Harnett Streets reached the militiamen of the Light Infantry and the Naval Reserves. The men began to muster. They readied their weapons. Their rapid-fire guns were mounted on horse-drawn wagons. The orders came to move out. The soldiers and sailors rushed to Brooklyn, the wagon wheels churning, the men holding on to their hats and clutching their rifles, the animals snorting and panting. The killing was just beginning.

__________________________________

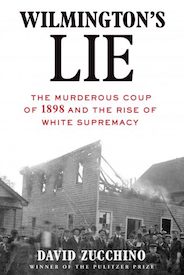

Excerpted from Wilmington’s Lie by David Zucchino. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2020 by David Zucchino.