William “Gatz” Hjortsberg had everything going for him except time. Days before the diagnosis in early March—pancreatic cancer, stage IV—Gatz had finished the long-awaited sequel to his groundbreaking novel, Falling Angel. He’d hoped to have enough time to edit it. But the end came faster than anyone expected. He was in hospice care at home in Livingston, MT, and feeling strong enough to entertain visitors, including his old friend, Tom McGuane, who told him how much he liked the new book. Gatz was so encouraged that he decided to try a round of chemo to see if it could give him an extra month or so to get the book to a publisher. That was Thursday, April 20th.

I live around the corner from Gatz and his wife, the artist Janie Camp, so on Saturday morning I knocked on their door with a plate of fresh banana bread, thinking he might be able to eat a bite or two. He smiled when he saw me, but he was done with food or drink.

Gatz—a childhood nickname that evolved from his unpronounceable last name—had a genius for storytelling that he translated into a large and diverse body of work, including essays, novels, screenplays, and a captivating, encyclopedic biography of Richard Brautigan, a former friend and neighbor. Hjortsberg and Brautigan were part of a cohort of writers and actors who adopted Montana as home in the late 1960s and 70s, including McGuane, Peter Fonda, Warren Oates, Jeff Bridges, Tim Cahill, Russell Chatham, and, at least part-time, Jim Harrison. A lot of the ones who survived the gunfire and divorce lawyers stuck around, including Gatz.

William Hjortsberg was born in New York City on February 23, 1941, the only child of a Swedish restaurateur and his Swiss wife. He lived the high life until his father died when he was ten, leaving no money. His mother worked as a hotel maid to put him through private school while they lived in a transient hotel on Amsterdam Avenue. Gatz worked his way through Dartmouth College, attended the Yale School of Drama—where he met McGuane—and spent two years at Stanford as a Stegner Fellow. During the 1960s Gatz and his first wife, Marian, bounced between the United States and various exotic locales, teaching, homesteading, and doing what hippies tend to do while bringing up their young daughter, Lorca. During the 70s they settled in the Paradise Valley, south of Livingston, where a son, Max, was born (and where the marriage eventually ended).

Gatz was an exceedingly original writer, with a passion for history, mystery, and the occult—and a flair for twisting it all into elegant plots with a sense of wicked fun. As John Leonard wrote in a New York Times review of Gatz’s first novel, Alp, in 1969, he was “a satanic S.J. Perelman… by way of Disney and de Sade.” It was sometimes hard to reconcile Gatz’s gruesome subject matter with his sunny, ebullient personality. He was a mischievous presence, a fascinating conversationalist, and the kindest, most generous of friends. The writer who detailed demonic orgies with the glee of an ax murderer was also a doting father and grandfather who patiently taught children to fish for trout. He kept an extensive collection of antique toys. He loved art. His totem, he said, was the penguin, the most cheerful bon vivant of the animal kingdom. And yet, there was the dark well from which he drew inspiration: “The door to my lower consciousness is always open,” he once said. “And the little lizard people who live down in there are always wriggling out and whispering nasty things.” In 1978 one of those nasty ideas grew into the best-selling Falling Angel, a supernatural detective novel. In 1987 it was adapted into the film, Angel Heart, starring Mickey Rourke, Lisa Bonet, and Robert DeNiro.

Gatz’s focus drifted to Hollywood, where he wrote Ridley Scott’s cult classic, Legend, and countless other scripts, some of which were even made into films. He made a good living from his screenplays, but he returned to letters, pursuing the definitive Brautigan biography with the demented zeal of an Ahab stalking his whale. Happily, Gatz’s obsession had a better ending. Jubilee Hitchhiker, which he labored over for two decades, was well received when it was published in 2012.

His accomplishments were often eclipsed by those of his famous buddies (even at his peak, reviewers described him as “underappreciated”), but Gatz had recently been experiencing late-career revival. He published a new novel, Mañana, in 2015, and was working on some other projects when he had a revelation. The sequel to Falling Angel had been percolating in his mind for years, but he didn’t know how it ended. Suddenly he did. Gatz started writing immediately.

I met Gatz when my husband Bill Campbell and I moved to Livingston 20 years ago. It was easy to be his friend; he was irresistible. And when he fell in love with Janie Camp, who lived practically next door, Gatz became a neighbor, too. The last time we spoke he joked that we should have installed tracks or, better yet, a zip-line between our yards to make cocktail hour more efficient.

Maybe Gatz was so adept at fantasy and fairytales because he was childlike himself. A friend who grew up around him told me that children loved Gatz because he never patronized them. “He always listened, took you completely seriously. Once you were human you were part of the game,” she said. Gatz embraced his stepsons, Michel Leroy and Jake Camp, as his own. He was close to his daughter, Lorca, who works for a toy company based in Los Angeles, and Max, a poet and conservationist, who lives in Livingston with his wife, Anna (the younger daughter of Jim Harrison) and their son Silas.

After Gatz was diagnosed with cancer, he and his son Max made plans to prepare the Falling Angel sequel for submission to publishers. A few weeks ago, at a memorial for Jim Harrison, Max slipped his old pal Tom McGuane a thumb drive of the manuscript.

On Monday, April 17, Tom popped by to visit Gatz and stayed for a couple of hours. When he left, Gatz was elated. I sent McGuane an email to ask him what he thought of the sequel. He wrote: “It is extraordinarily imaginative and detailed and I think might remind any reader why The Los Angeles Times said that its predecessor, Falling Angel, was an absolute game changer.” He added what he told Gatz: “I intend to help the new book find its way however I can.“

When I walked through the door the next Saturday morning, it was obvious that Gatz wasn’t going to get the time he’d hoped for. The book was his only unfinished business. He had no other regrets, he told his doctor, who had visited him the night before and then placed a call to hospice. He was hoping to have a more festive death, he said, one with music and friends gathered around. But there was no time for it.

I know he would like you to hear this: His last hours on this planet were peaceful. The drugs worked and there was no pain. He was never afraid. Max arrived, and a few friends and relatives came by to help with what was needed. Gatz smiled at everyone. His grip was strong and he knew us all. The last thing I saw him do was put his arm around Janie to comfort her. Courtly to the end. Gatz died at 9:15pm Saturday.

Because this is a very small town we knew that the undertaker, Colin, was asleep, because he lives with his young family right next door to me and Bill and we saw their lights were out. But when Janie was ready to let the hospice nurse call, Colin answered the phone and came by a few minutes later. It was a neighborly affair.

The sad news spread through Livingston before it got out into the world. Glenn Godward opened up the Park Place Tavern on a Sunday afternoon for an impromptu wake. Glenn’s place is a favorite watering hole for local novelists, journalists, artists, ranchers and poets—Jim Harrison used to position himself at the patio entrance like Cerberus with a taste for cabernet. The whole damn town must have been there that day. All that was missing was Gatz’s roaring chainsaw of a laugh, a sound that could cut through any level of pandemonium. Gatz, who never missed a good party, would have enjoyed it. God, I’ll miss hearing that voice. We all will.

__________________________________

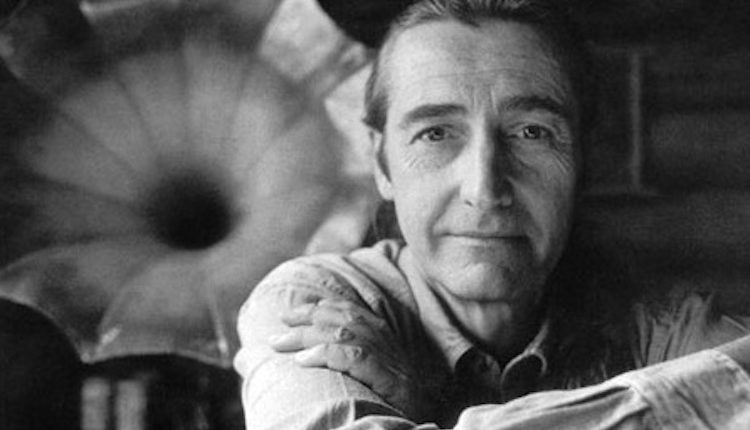

Feature photo by Michael Katakis