The harried, hardworking chefs and restaurateurs who find themselves on the wrong end of a harsh review are under no obligation to believe that the overfed critic in the corner is just doing his or her job, of course. There’s a scene in Jon Favreau’s movie Chef where Favreau’s character, a talented, beleaguered cook named Carl Casper, emerges from the kitchen in a rage to confront the glowering, all-powerful restaurant critic, who happens to be played, with a kind of delicious, charismatic menace, by my brother Oliver.

I’ve taken my brother out to restaurants many times in the real world, although, like me, he’s sometimes on a diet, and having him sitting at the table of a popular, just-opened restaurant in New York is a little like posting a large sign above us on the wall announcing in giant letters that Adam Platt Dines Here. Sometimes chefs who recognize his face from the movies and television will send out complimentary side dishes and slices of pie, and as a creative soul who sympathizes much more with the talent in the kitchen than with appraising, nitpicking critics like his older brother, he’ll often accept these illicit gifts happily and gobble them down whole.

Like all great theater, Jon Favreau’s movie is filled with moments of hyperbole and also moments of absolute truth. When the director was working on his script, trying to summon up the most horrible things a critic could possibly write about a restaurant chef’s cooking, Oliver asked me to send lines from my own most viciously negative reviews and from other inspired takedowns, like A. A. Gill’s famous carpet-bombing in Vanity Fair of Johnny Apple’s favorite Parisian bistro L’Ami Louis, with its “dung brown” walls and livery, vein-covered lobes of foie gras, which Gill described as tasting “faintly of gut-scented butter or pressed liposuction.” My pathetic efforts didn’t sound vicious at all compared to Gill’s, of course, but even his were tame compared to the thunderbolts that Oliver’s Ramsey Michel ended up letting loose on the unfortunate Carl Casper in the movie, which, as the title indicates, is written from the cook’s point of view.

In the excellent showdown scene between critic and chef, which takes place early in the film, the glowering, imperious Ramsey Michel is tracked by the camera from behind as he makes his slow, grand entrance into the comically named “Gauloise” restaurant like a villainous professional wrestler entering the ring. Never mind that this villain critic’s stylish, tailored brown silk jacket isn’t rumpled or stained with streaks of A.1. sauce the way mine often is, or that Mr. Michel is dining alone this evening, which most working critics don’t do very often. Never mind that the owner of the restaurant, a fevered, slightly overblown caricature culled from the collective kitchen slave imagination and played by Dustin Hoffman, has unaccountably commanded the chef to scrap that night’s trendy, cutting-edge tasting menu in favor, among other things, of a tired molten chocolate lava cake dating from many decades before, which the arch villain critic has already described as “overcooked, needy, and yet, by some miracle, also irrelevant.”

The critic’s grand entrance into the dining room, however, is an inspired and accurate bit of theater, and so is the chef ’s anger when, after years of pent-up frustration and rage, he bursts into the dining room, to the horror of Dustin Hoffman and all the other actors on that carefully orchestrated stage, and finally gives this haughty critic a piece of his mind.

If a transcript existed of Rich Torrisi and Mario Carbone’s muttered dialogue from deep in the Carbone basement just before the Showdown at ZZ’s Clam Bar, it might not sound very different from the one Favreau wrote for his aggravated hero, Carl Casper, in Chef. He calls his tormentor an asshole “who just sits there and eats and vomits these words back,” and he accuses him, not without reason, of having no idea how a molten chocolate lava cake is actually prepared (hint: it’s the timing). “It hurts, it fucking hurts when you write this shit!” he cries, before doing what countless chefs have probably fantasized about doing, which is to grab the offending chocolate cake, squeeze it in his fist, and throw the remains back down on Ramsey Michel’s plate.

Meanwhile, Oliver sits still and says nothing as the chef rages on, with an impassive look on his face. Maybe he was aided in this portrayal by memories of his poor brother sitting impassively on the job, pushing around servings of stale desserts, like molten chocolate lava cake, with his fork. Another inspiration could have been our own father, who as an ambassador in countries that had long, tortured histories with the United States, like Pakistan and the Philippines, used to cultivate what he called “the boiled-owl look” when irate officials criticized him in public. He didn’t take their anger personally; he was only the messenger, and just like the critic, who is a consumer, not a cook, and whose job it is to represent the nation of paying customers, not the tortured, hardworking souls in the kitchen, he was sometimes the bearer of unwelcome news.

This caricatured role—the glowering pro wrestler–style villain—comes with the territory when you sign up to be a restaurant critic, of course, although the levels of imagined villainy and supposed influence often depend on the influence of the publication for which the critic is writing. Friends of mine who ascended to top critic jobs at papers in New York and London have told me that it takes some time to get accustomed to the tsunami of scrutiny, insults, ill will, and petty criticism that comes your way if you’ve spent relatively peaceful years writing for less influential publications.

No one experienced more vitriol apparently than Gill, who was famously dyslexic and a recovering alcoholic; he was known for dictating his stories and observations over the phone to his editor, who would commit them to paper, then send the piece back to Gill just before deadline to be retouched. Like the antihero in a comic book, Gill drew power from the rage of his imagined enemies, someone at the Sunday Times once told me, and he took delight in driving them into mad apoplectic fits of rage and despair.

Once, after a particularly savage review, a box arrived at the newspaper offices addressed to the “London Sunday Times Restaurant Critic.” When it was opened—no doubt by a team of highly trained specialists—they found a note inside, propped next to a single, mercifully dried-out human turd. “From one Arsehole to Another” read the note in what was, no doubt, a twisted, scraggly script. Gill never saw the offending package, I’m told, but when the note was read to him over the telephone, I like to imagine he let out a long, cackling, slightly villainous-sounding laugh of happy delight.

I never took pleasure in writing a critical review, and although, as far as I know, I’ve never received a signature A. A. Gill care package in the mail, I’ve received many letters and had other occasional uncomfortable face-to-face encounters like the one at ZZ’s. Such encounters happened more often downtown in SoHo, Tribeca, and Greenwich Village, where many members of the writing and restaurant community lived before the mass exodus of Manhattan’s creative freelance culture out to the wilds of Brooklyn and Queens. The sense of aggrievement and occasional outrage directed at me began to increase when the magazine asked me in 2008 to concoct its inaugural star system of rating restaurants.

Star systems—like the one invented by the ingenious mandarins at the Michelin Tire Company as a gimmick to entice bourgeois Frenchmen to travel the roads of the country after the war, preferably on sets of their tires, to find a good meal, using their Michelin Guides—have always been a controversial but useful part of the restaurant landscape. For chefs, star ratings are both an object of obsession and good for business; for consumers (and editors), they’re a source of endless argument and discussion, as well as an imperfect tool for bringing a sense of objective order to a sprawling, highly subjective world. But ask working critics whether they like star ratings and, depending on how many martinis they’ve imbibed that evening, you’re likely to get plenty of scowling boiled-owl looks, followed by a litany of complaints.

No matter what kind of system I managed to devise, the chefs would have one more reason to hate me.“Boy, are you screwed,” a former critic friend of mine had said when I called her to ask for advice on creating my system, which was supposed to be roughly equivalent to the famous New York Times system devised by Craig Claiborne, but not exactly the same. There were already too many types of star systems in the crowded firmament, she said, and one more would just add to the confusion. The most venerable systems, like the Michelin and Times systems, tended to skew in favor of expensive, Continental-style establishments, leaving restaurants that were also worthy of inclusion but that offered more international styles and cuisines, like Japanese, Italian, or even Chinese cooking, out in the cold. Readers would fixate on the stars instead of my carefully crafted reviews, she cautioned, which was one reason why stylish writers like Gill in London and the great bard of the Los Angeles restaurant scene, Jonathan Gold, never used them. I would become a prisoner of my stars, just as the old white tablecloth dining tradition was being replaced by a more raucous, democratic style. No matter what kind of system I managed to devise, she concluded, the chefs would have one more reason to hate me.

All of these dire prophesies would come to pass during my star-crossed, decade-long career as a haughty, star-giving critic, before the practice was mercifully discontinued by the magazine. My tortured passive-aggressive solution to copying the vaunted four-star Times franchise without doing so exactly was to introduce, in a cover story, with much elaborate fanfare, a five-star New York magazine system ranging from “good” (one star) to “ethereal” (five stars), although discerning readers (and increasingly irritated chefs) would soon notice that I rarely ever bestowed the fifth star at all. In ten years, I gave only two restaurants the vaunted five-star prize, and in both cases (Eleven Madison Park, run by the talented Swiss chef Daniel Humm, and a ridiculously priced sushi bar called Masa) I ended up taking that fifth star away in a dramatic huff the following year. I rarely ever gave out four stars (to an “exceptional” restaurant, according to the tortured Platt system), and three-star reviews became increasingly rare as the tectonic leveling of the dining world, which was already under way when our system was introduced, continued to accelerate.

The stately Continental fine-dining culture would disappear under a blizzard of comfort food fads, noisy No Reservations bar-restaurants, and trendy ramshackle pizza destinations like Roberta’s, which opened in 2008 among the truck docks of Bushwick in Brooklyn, a place that snooty Manhattan gourmets would never have dreamed of visiting in the not-so-distant past when lofty, Alain Ducasse–style palaces in midtown were the gold standard of the French-centric, star-obsessed restaurant era.

Over the years, as I tapped out a steady stream of one- and two-star reviews, I would find myself endlessly repeating the restaurant critic’s mantra (“One star means good!”) while trying to dream up catchy new buzzwords to describe this shift from what used to be called “le haute cuisine” to a more democratic, less formal style of dining. “Haute Barnyard” was a phrase I attempted to popularize as more and more decorated, accomplished chefs like Dan Barber at Blue Hill and Tom Colicchio at his hit restaurant, Craft, began to highlight locally grown chickens and other boutique barnyard products on their stripped-down (though still expensive) big-city menus.

The “Kitchen Slave Revolution” was the term I used to describe the culture of tattooed backroom cooks who were moving from the shadows of the closed, Continental-style kitchens where they’d resided for decades out into a casual, open kitchen, which in this new world would become a glamorous kind of stage, and then from there, thanks to the wildfire popularity of the internet and the charisma of cooks like Tony Bourdain and David Chang, out into the buzzing popular culture at large.

Still, the most ambitious New York chefs tended to fixate on the stars, and now and then their outrage would bubble up, like the Carl Casper scene in Jon Favreau’s movie, into public view. One of the few three-star (“excellent”) reviews I did write back in those early days was for an extravagant Italian venture called Del Posto, which Mario Batali and his business partner Joe Bastianich, whose West Village establishment, Babbo, was the enormously influential hit restaurant of its era, opened in a tall, slightly drafty space in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, by the Hudson River. “Vegas on the Hudson” was the title of my generally favorable review, although Batali, who was more notorious in those days for his undoubted skills as a cook and for his cheerful “Molto Mario” personality than for the abusive and crude sexual behavior that later would sink his career, was not amused.

“Platt’s a miserable fuck,” he told a writer for Grub Street, shortly after sending out for a bottle of vodka and some tonic. “He can’t help himself,” he explained to Tony Bourdain, who had accompanied his friend Mario to a book signing for one of the early heroes and inspirations of the Kitchen Slave movement, the wild man London chef Marco Pierre White. “His understanding about the star system is misguided,” huffed Mario, presumably as he chugged one vodka tonic after another. “He’s not about awarding stars, he’s about taking them away, you know?”

As it zipped around what was still a relatively modest online restaurant community back in those days, the “miserable fuck” line was happily repeated to me by amused editors, friends, and slightly startled members of my family, including my mother, who wondered out loud what her son had done to make this chef person so horribly upset. I told her that I’d just been doing my job, and as usual, I maintained the signature Platt boiled-owl look in public and never responded to Batali. At the end of the year, however, when it came time to compose that other unhappy burden carried by most working restaurant writers, especially in the world of service magazines, the annual end-of-the-year wrap-up of all the new and trendy places to eat around town, I took my quiet revenge.

My long-suffering editor at the time, Jon Gluck, and I used to call this yearly restaurant cover package “the monster,” because it covered hundreds of restaurants and took thousands of words and several weeks of labor-intensive eating to research and write. That year when I handed in the 7000-word monster, I quietly deleted Batali’s name everywhere in the text and referred to all of his restaurants, including Del Posto, as “Bastianich establishments,” in reference to his partners, Joe Bastianich and the first lady of Italian cooking in New York, Lidia Bastianich. When the monster was published just after the new year, no one noticed, of course, except for the sensitive, bloviating, image-conscious chef himself. “Tell Platt that I can see what he’s doing,” Batali told one of the food editors with what I like to imagine was a tone of aggrieved, menacing outrage in his voice when they called about another story on one of his restaurants. “And tell him that I don’t like it.”

————————————————

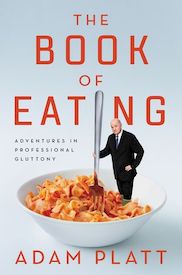

From The Book of Eating by Adam Platt. Copyright © 2019 by Adam Platt. Reprinted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.