The past, as we have been told so many times, is a foreign country where things are done differently. This may be true—indeed it patently is true when it comes to morals or customs, the role of women, aristocratic government, and a million other elements of our daily lives. But there are similarities, too. Ambition, envy, rage, greed, kindness, selflessness, and, above all, love have always been as powerful in motivating choices as they are today. This is a story of people who lived two centuries ago, and yet much of what they desired, much of what they resented, and the passions raging in their hearts were only too like the dramas being played out in our own ways, in our own time…

* * * *

It did not look like a city on the brink of war; still less like the capital of a country that had been torn from one kingdom and annexed by another barely three months before. Brussels in June 1815 could have been en fête, with busy, colorful stalls in the markets and brightly painted, open carriages bowling down the wide thoroughfares, ferrying their cargoes of great ladies and their daughters to pressing social engagements. No one would have guessed that the emperor Napoléon was on the march and might encamp by the edge of the town at any moment.

None of which was of much interest to Sophia Trenchard as she pushed through the crowds in a determined manner that rather belied her eighteen years. Like any well-brought-up young woman, especially in an alien land, she was accompanied by her maid, Jane Croft, who, at twenty-two, was four years older than her mistress. Although if either of them could be said to be protecting the other from a bruising encounter with a fellow pedestrian, it would be Sophia, who looked ready for anything. She was pretty, very pretty even, in that classic blonde, blue-eyed English way, but the cut-glass set of her mouth made it clear that this particular girl would not need Mama’s permission to embark on an adventure. “Do hurry, or he’ll have left for luncheon and our journey will have been wasted.” She was at that period of her life that almost everyone must pass through, when childhood is done with and a faux maturity, untrammeled by experience, gives one a sense that anything is possible until the arrival of real adulthood proves conclusively that it is not.

“I’m going as fast as I can, miss,” murmured Jane, and, as if to prove her words, a hurrying Hussar pushed her backward without even pausing to learn if she was hurt. “It’s like a battleground here.” Jane was not a beauty, like her young mistress, but she had a spirited face, strong and ruddy, if more suited to country lanes than city streets.

She was quite determined in her way, and her young mistress liked her for it. “Don’t be so feeble.” Sophia had almost reached her destination, turning off the main street into a yard that might once have been a cattle market but which had now been commandeered by the army for what looked like a supply depot. Large carts unloaded cases and sacks and crates that were being carried to surrounding warehouses, and there seemed to be a constant stream of officers from every regiment, conferring and sometimes quarreling as they moved around in groups. The arrival of a striking young woman and her maid naturally attracted some attention, and the conversation, for a moment, was quelled and almost ceased. “Please don’t trouble yourselves,” said Sophia, looking around calmly. “I’m here to see my father, Mr. Trenchard.”

A young man stepped forward. “Do you know the way, Miss Trenchard?”

“I do. Thank you.” She walked toward a slightly more important-looking entrance to the main building, and, followed by the trembling Jane, she climbed the stairs to the first floor. Here she found more officers apparently waiting to be admitted, but this was a discipline to which Sophia was not prepared to submit. She pushed open the door. “You stay here,” she said. Jane dropped back, rather enjoying the curiosity of the men.

The room Sophia entered was a large one, light and commodious, with a handsome desk in smooth mahogany and other furniture in keeping with the style, but it was a setting for commerce rather than Society, a place of work, not play. In one corner, a portly man in his early forties was lecturing a brilliantly uniformed officer. “Who the devil is come to interrupt me!” He spun around, but at the sight of his daughter his mood changed and an endearing smile lit up his angry red face. “Well?” he said. But she looked at the officer. Her father nodded. “Captain Cooper, you must excuse me.”

“That’s all very well, Trenchard—“

“Trenchard?”

“Mr. Trenchard. But we must have the flour by tonight. My commanding officer made me promise not to return without it.”

“And I promise to do my level best, Captain.” The officer was clearly irritated but he was obliged to accept this, since he was not going to get anything better. With a nod he retired, and the father was alone with his girl. “Have you got it?” His excitement was palpable. There was something charming in his enthusiasm, this plump, balding master of business who was suddenly as excited as a child on Christmas Eve.

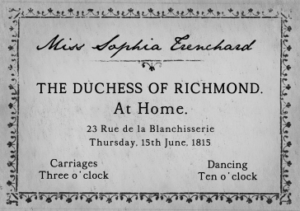

Very slowly, squeezing the last drop out of the moment, Sophia opened her reticule and carefully removed some squares of white pasteboard. “I have three,” she said, savoring her triumph, “one for you, one for Mama, and one for me.”

He almost tore them from her hand. If he had been without food and water for a month, he could not have been more anxious. The copperplate printing was simple and elegant.

He stared at the card. “I suppose Lord Bellasis will be dining there?”

“She is his aunt.”

“Of course.”

“There won’t be a dinner. Not a proper one. Just the family and a few people who are staying with them.”

“They always say there’s no dinner, but there usually is.”

“You didn’t expect to be asked?” He’d dreamed, but he hadn’t expected it.

“No, no. I am content.”

“Edmund says there’s to be a supper sometime after midnight.”

“Don’t call him Edmund to anyone but me.” Still, his mood was gleeful again, his momentary disappointment already swept aside by the thought of what lay in store for them. “You must go back to your mother. She’ll need every minute to prepare.”

Sophia was too young and too full of unearned confidence to be quite aware of the enormity of what she had achieved. Besides which, she was more practical in these things than her starstruck papa. “It’s too late to have anything made.”

“But not too late to have things brought up to standard.”

“She won’t want to go.”

“She will, because she must.”

Sophia started toward the door, but then another thought struck her. “When shall we tell her?” she asked, staring at her father. He was caught out by the question and started to fiddle with the gold fobs on his watch chain. It was an odd moment. Things were just as they had been a moment before, and yet somehow the tone and substance had changed. It would have been clear to any outside observer that the subject they were discussing was suddenly more serious than the choice of clothes for the Duchess’s ball.

Trenchard was very definite in his response. “Not yet. It must all be properly managed. We should take our lead from him. Now go. And send that blithering idiot back in.” His daughter did as she was told and slipped out of the room, but James Trenchard was still curiously preoccupied in her absence. There was shouting from the street below, and he wandered over to the window to look down on an officer and a trader arguing. Then the door opened and Captain Cooper entered. Trenchard nodded to him. It was time for business as usual.

Sophia was right. Her mother did not want to go to the ball. “We’ve only been asked because somebody’s let her down.”

“What difference does that make?”

“It’s so silly.” Mrs. Trenchard shook her head. “We won’t know a soul there.”

“Papa will know people.”

There were times when Anne Trenchard was irritated by her children. They knew little of life, for all their condescension. They had been spoiled from childhood, indulged by their father, until they both took their good fortune for granted and scarcely gave it a thought. They knew nothing of the journey their parents had made to reach their present position, while their mother remembered every tiny, stone-strewn step. “He will know some officers who come to his place of work to give him orders. They, in their turn, will be astonished to find they are sharing a ballroom with the man who supplies their men with bread and ale.”

“I hope you won’t talk like this to Lord Bellasis.” Mrs. Trenchard’s face softened slightly.

“My dear”—she took her daughter’s hand in hers—“beware of castles in the air.” Sophia snatched her fingers back.

“Of course, you won’t believe him capable of honorable intentions.”

“On the contrary, I am sure Lord Bellasis is an honorable man. He is certainly a very pleasant one.”

“Well, then.”

“But he is the eldest son of an earl, my child, with all the responsibilities such a position entails. He cannot choose his wife only to suit his heart. I am not angry. You’re both young and good-looking, and you have enjoyed a little flirtation that has harmed neither of you. So far.” Her emphasis on the last two words was a clear indication of where she was headed. “But it must end before there is any damaging talk, Sophia, or you will be the one to suffer, not he.”

“And it doesn’t tell you anything? That he has secured us invitations to his aunt’s ball?”

“It tells me that you are a lovely girl and he wishes to please you. He could not have managed such a thing in London, but in Brussels everything is colored by war, and so the normal rules do not apply.” This last irritated Sophia more than ever.

“You mean that by the normal rules we are not acceptable as company for the Duchess’s friends?” Mrs. Trenchard was, in her way, quite as strong as her daughter.

“That is exactly what I mean, and you know it to be true.”

“Papa would not agree.”

“Your father has successfully traveled a long way, longer than most people could even imagine, and so he does not see the natural barriers that will prevent him going much further. Be content with who we are. Your father has done very well in the world. It is something for you to be proud of.” The door opened and Mrs. Trenchard’s maid came in, carrying a dress for the evening.

“Am I too early, ma’am?”

“No, no, Ellis. Come in. We were finished, weren’t we?”

“If you say so, Mama.” Sophia left the room, but the set of her chin did not mark her as one of the vanquished. It was obvious from the way that Ellis went about her duties in pointed silence that she was burning with curiosity as to what the row had been about, but Anne let her dangle for a few minutes before she spoke, waiting while Ellis unfastened her afternoon dress, allowing her to slip it away from her shoulders.

“We have been invited to the Duchess of Richmond’s ball on the fifteenth.”

“Never!” Mary Ellis was usually more than adept at keeping her feelings concealed, but this amazing information had caught her off guard. She recovered quickly.

“That is to say, we should make a decision on your gown, ma’am. I’ll need time to prepare it, if it’s to be just so.”

“What about the dark blue silk? It hasn’t been out too much this season. Maybe you could find some black lace for the neck and sleeves to give it a bit of a lift.” Anne Trenchard was a practical woman but not entirely devoid of vanity. She had maintained her figure, and with her neat profile and auburn hair she could certainly be called handsome. She just did not let her awareness of it make her a fool.

Ellis knelt to hold open a straw-colored taffeta evening dress for her mistress to step into. “And jewels, ma’am?”

“I hadn’t really thought. I’ll wear what I’ve got, I suppose.” She turned to allow the maid to start fastening the frock with gilded pins down the back. She had been firm with Sophia, but she didn’t regret it. Sophia lived in a dream, like her father, and dreams could get people into trouble if they were not careful. Almost in spite of herself, Anne smiled. She’d said that James had come a long way, but sometimes she doubted that even Sophia knew quite how far.

“I expect Lord Bellasis arranged the tickets for the ball?” Ellis glanced up from her position at Anne Trenchard’s feet, changing her mistress’s slippers. She could see at once that her the question had annoyed Mrs. Trenchard. Why should a maid wonder aloud at how they had been included on such an Olympian guest list? Or why they were invited to anything, for that matter. She chose not to answer and ignored the question. But it made her ponder the strangeness of their lives in Brussels and how things had altered for them since James had caught the eye of the great Duke of Wellington. It was true that no matter the shortages, whatever the ferocity of the fighting, however the countryside had been laid bare, James could always conjure up supplies from somewhere. The Duke called him “the Magician,” and so he was, or seemed to be. But his success had only fanned his overweening ambition to scale the unscalable heights of Society, and his social climbing was getting worse. James Trenchard, son of a market trader, whom Anne’s own father had forbidden her to marry, thought it the most natural thing in the world that they should be entertained by a duchess. She would have called his ambitions ridiculous, except that they had the uncanny habit of coming true.

Anne was much better educated than her husband—as the daughter of a schoolteacher she was bound to be—and when they met, she was a catch dizzyingly high above him, but she knew well enough that he had far outpaced her now. Indeed, she had begun to wonder how much further she could hope to keep up with his fantastical ascent; or, when the children were grown, whether she should retire to a simple country cottage and leave him to battle his way up the mountain alone.

Ellis was naturally aware that her mistress’s silence meant she had spoken out of turn. She thought about saying something flattering to work her way back in, but then decided to remain quiet and let the storm blow itself out.

The door opened and James looked around it. “She’s told you, then? He’s done it.”

Anne glanced at her maid. “Thank you, Ellis. If you could come back in a little while?”

Ellis retreated. James could not resist a smile. “You tell me off for having ideas above my station, yet the way you dismiss your maid puts me in mind of the Duchess herself.”

Anne bristled. “I hope not.”

“Why? What have you got against her?”

“I have nothing against her, for the simple reason that I do not know her, and nor do you.” Anne was keen to inject a note of reality into this absurd and dangerous nonsense. “Which is why we should not allow ourselves to be foisted on the wretched woman, taking up places in her crowded ballroom that would more properly have been given to her own acquaintance.”

But James was too excited to be talked down. “You don’t mean that?”

“I do, but I know you won’t listen.”

She was right. She could not hope to dampen his joy. “What a chance it is, Annie! You know the Duke will be there? Two dukes, for that matter. My commander and our hostess’s husband.”

“I suppose.”

“And reigning princes, too.” He stopped, full to bursting with the excitement of it all. “James Trenchard, who started at a stall in Covent Garden, must get himself ready to dance with a princess.”

“You will not ask any of them to dance. You would only embarrass us both.”

“We’ll see.”

“I mean it. It’s bad enough that you encourage Sophia.”

James frowned. “You don’t believe it, but the boy is sincere. I’m sure of it.”

Anne shook her head impatiently. “You are nothing of the sort. Lord Bellasis may even think he’s sincere, but he’s out of her reach. He is not his own master, and nothing proper can come of it.”

There was a rattle in the streets, and she went to investigate. The windows of her bedroom overlooked a wide and busy thoroughfare. Below, some soldiers in scarlet uniforms, the sun bouncing off their gold braid, were marching past. How strange, she thought, with evidence of imminent fighting all around, that we should be discussing a ball.

“I don’t know as much.” James would not give up his fancies easily. Anne turned back toward the room. Her husband had assumed an expression like a cornered four-year-old. “Well, I do. And if she comes to any harm through this nonsense, I will hold you personally responsible.”

“Very well.”

“As for blackmailing the poor young man into begging his aunt for invitations, it is all so unspeakably humiliating.”

James had had enough. “You won’t spoil it. I won’t allow you to.”

“I don’t need to spoil it. It will spoil itself.” That was the end. He stormed off to change for dinner, and she rang the bell for Ellis’s return.

Anne was unhappy with herself. She did not like to quarrel, and yet there was something about the whole episode she felt undermined by. She liked her life. They were rich now, successful, sought after in the trading community of London, and yet James insisted on wrecking things by always wanting more. She must be pushed into an endless series of rooms where they were not liked or appreciated. She would be forced to make conversation with men and women who secretly—or not so secretly—despised them. And all of this when, if James would only allow it, they could have lived in an atmosphere of comfort and respect. But even as she thought these things, she knew she couldn’t stop her husband. No one could. That was the nature of the man.

*x*x*x*

So much has been written about the Duchess of Richmond’s ball over the years that it has assumed the splendor and majesty of the coronation pageant of a medieval queen. It has figured in every type of fiction, and each visual representation of the evening has been grander than the one that went before. Henry O’Neil’s painting of 1868 has the ball taking place in a vast and crowded palace, lined with huge marble columns, packed with seemingly hundreds of guests weeping in sorrow and terror and looking more glamorous than a chorus line at Drury Lane. Like so many iconic moments of history, the reality was quite different.

The Richmonds had arrived in Brussels partly as a cost-cutting exercise, to keep living expenses down by spending a few years abroad, and partly as a show of solidarity with their great friend the Duke of Wellington, who had made his headquarters there. Richmond himself, a former soldier, was to be given the task of organizing the defense of Brussels, should the worst happen and the enemy invade. He accepted. He knew the work would be largely administrative, but it was a job that needed to be done, and it would give him the satisfaction of feeling that he was part of the war effort and not simply an idle onlooker. As he knew well enough, there were plenty of those in the city.

The palaces of Brussels were in limited supply, and most were already spoken for, and so finally they settled on a house formerly occupied by a fashionable coachbuilder. It was on the rue de la Blanchisserie, literally “the street of the laundry,” causing Wellington to christen the Richmonds’ new home the Wash House, a joke the Duchess enjoyed rather less than her husband. What we would call the coachbuilder’s showroom was a large, barnlike structure to the left of the front door, reached through a small office where customers had once discussed upholstery and other optional extras but that the memoirs of the Richmonds’ third daughter, Lady Georgiana Lennox, transmogrified into an “anteroom.” The space where the coaches had been placed on display was wallpapered with roses on trellis, and the room was deemed sufficient for a ball.

The Duchess of Richmond had taken her whole family with her to the Continent, and the girls especially were aching for some excitement, and so a party was planned. Then, at the beginning of June, Napoléon, who had escaped from his exile on Elba earlier that year, left Paris and came looking for the allied forces. The Duchess had asked Wellington whether it was quite in order for her to continue with her pleasure scheme, and she was assured that it was. Indeed, it was the Duke’s express wish that the ball should go ahead, as a demonstration of English sangfroid, to show plainly that even the ladies were not much disturbed by the thought of the French emperor on the march and declined to put off their entertainment. But of course, that was all very well…

From BELGRAVIA. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing, Copyright © The Orion Publishing Group Limited 2016.