1.

On one of seven pillars in the dungeon of the Château de Chillon on the shores of Lake Geneva, Lord Byron carved his name.

2.

For the tourist, this can be a little confusing. Although he’d been exiled from England, notoriously labeled by one woman as “mad, bad and dangerous to know,” Byron was never a prisoner here.

3.

The woman, Lady Lamb, eventually became his lover. When Byron left her, she attempted to stab herself, then sent him a pubic hair enclosed in a letter signed, “Your wild antelope.”

4.

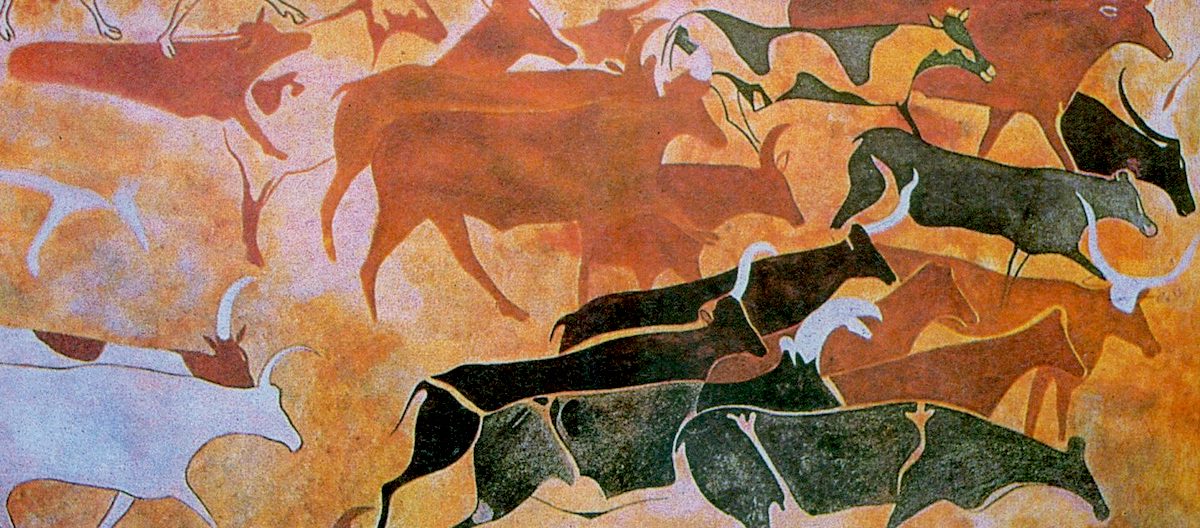

Some of the earliest traces of human art are found in cave paintings: the antelope, bison, and horses cantering across the walls of an underwater cave near Marseille, alongside what appears to be a man with a seal’s head; depictions of babirusa, or pig deer, in Indonesia; an abstract red splotch in northern Spain; the outline of an adolescent hand, stenciled into stone over 30,000 years ago.

5.

This type of primitive scrawl has always moved me, as much as any work of literature safely confined between covers. The tree stump initials, the bathroom stall revelations.

Like marginalia, but less cloying. No need for pretension on a park bench.

6.

The silent wishes of a West Berliner to someone on the other side of the wall: Happy birthday, Sabine.

7.

An apparent disregard for social rules endows the words with weight. The unexpected context supplies heft. And the enduring materials on which they are etched lend the letters their longevity.

8.

The graffiti of Pompeii, preserved over centuries by volcanic ash, lets us know that, among others, Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here on October 3, 78 BC.

9.

We get the word graffiti from the Italian. “To scratch.”

10.

Was Byron’s little impulse simply a primitive urge, then, or something more profound?

11.

Or perhaps the primitive is to us, at evolution’s other end, inherently profound?

12.

Of course, when it comes to graffiti, context is everything. Profanity on the Berlin Wall invites immediate pardon, while in the bathroom stall it’s just petty.

13.

Bar of Athictus, Pompeii: I screwed the barmaid.

14.

I can still see the trite sayings and revolutionary cries of that narrow one-stall bathroom in my favorite Seattle coffee shop, where you told me you’d gone to cry when you realized I was leaving.

I had never seen you cry before and could hardly imagine it.

15.

In academic circles, bathroom graffiti goes by the widely accepted term latrinalia, a name coined by the folklorist Alan Dundes, who believed the impulse to write on walls originated with “‘a primitive smearing impulse,’ the desire that infants allegedly have to handle and manipulate their feces.”

16.

The Roman poet Martial slammed one of his contemporaries with this first-century AD put-down: “if you aim at getting your name into verse, seek, I advise you, some sot of a poet from some dark den, who writes, with coarse charcoal and crumbling chalk, verses which people read as they ease themselves.”

17.

“Graffiti is one of the few tools you have if you have almost nothing,” writes the street artist Banksy. “And even if you don’t come up with a picture to cure world poverty you can make someone smile while they’re having a piss.”

18.

In the art world, graffiti has evolved into a culturally accepted and even highly lucrative practice. Curators and critics first woke to the potential of street art during the late 1970s when Jean-Michel Basquiat, under the alter ego SAMO, began to leave pithy insights on the walls of the Lower East Side.

19.

At what point does the destructive become creative? What makes the primitive profound?

20.

Each time I returned to that café, I scanned the bathroom walls for some sign that you had been there and felt something for me. Even if it was just goodbye.

21.

Graffiti at Pompeii: Cruel Lalagus, why do you not love me?

22.

Byron’s name, on the other hand, is not hard to miss. The crudely carved letters stand out against other less legible markings in ALL CAPs that become shorter by degrees, slanting like a child’s hand, so that when you step back from the pillar, the name appears like a small pennant waving in the dim silence of the vaulted chamber.

23.

Byron, of course, was not the poet’s first name. But it is unlikely that GEORGE or GORDON, or, god forbid, GG, would have stood the test of time.

24.

At first glance, this looks like an act of the ego: the adolescent impulse to spill out over the world, leaving sticky traces of itself on every surface it touches.

25.

Byron’s vandalism at Chillon was not his first offense. The habit began while he was a student at Harrow, where his name can still be found, etched into the walls of the fourth form room.

26.

Of course, by the time Byron was enrolled at Harrow, graffiti was more tradition than statement. The practice had become so commonplace that by the 19th century, the boarding school’s masters began encouraging students to add their signatures to what was quickly becoming a wall of illustrious alum. Today, Byron’s name appears alongside the likes of Anthony Trollope and seven prime ministers, including Churchill.

27.

According to school legend, a student named Warde carved such large letters that he was reprimanded after the first three and told to write smaller. Instead, he drew an even larger D and was expelled. Warde returned to finish the job under the cover of night, and was never seen on school premises again.

28.

Perhaps in compensation, Byron carved his own name three times.

29.

Some of Basquiat’s work is deceptively childlike, such as his 1983 drawing of a diminutive, Minion-like figure with crossed eyes and a toothy grin, sketched onto a coffee-stained page.

Below this tiny troll, Basquiat scrawled its name.

EGO.

30.

Gladiator barracks of Pompeii: Floronius, privileged soldier of the 7th Legion, was here.The women did not know of his presence. Only six women came to know, too few for such a stallion.

31.

After finishing his education—which included a stint at Cambridge, where he was known to keep a pet bear and carouse with both men and women—Byron set off to see the world, along with his friend Hobhouse, who packed one hundred pens and two gallons of ink for the journey.

When they arrived in Delphi, the travelers promptly carved their names into a pillar.

32.

Back in England, publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage brought Byron swift and furious fame. Enamored with his poetry, society began to conflate the author with the romantic heroes of his poems. “With false Ambition what had I to do?” Byron would later write in a poem dedicated to his half-sister Augusta. “Little with Love, and least of all with Fame; / And yet they came unsought, and with me grew, / And made me all which they can make—a name.”

33.

By then, Byron was accustomed to playing the hero. For example, while traveling in Turkey, he rescued one of his many alleged mistresses from some Turks, who had sewn the unfortunate woman into a sack and were about to cast her into the sea for her infidelities.

34.

House of Caecilius iucundus, Pompeii: Whoever loves, let him flourish. Let him perish who knows not love. Let him perish twice over whoever forbids love.

35.

Though Byron would have countless lovers throughout his life, his strongest bond was with his half-sister. “I have never ceased nor can cease to feel for a moment that perfect and boundless attachment which bound and binds me to you—” he wrote in a letter to Augusta, “which renders me utterly incapable of real love for any other human being—what could they be to me after you?”

36.

When Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne toured England in 1837, they would stop at Byron’s former estate. In the gardens, Hawthorne describes finding “a tree of twin stems . . . growing up side by side,” on which Byron had “carved his own name and that of his sister Augusta.”

37.

The Hawthornes would not have been shocked by the act of defacing property with vows of love. On a windowpane of their Old Manse in Concord, for example, where Nathaniel brought his bride, the lovers left a message, etched with the diamond of Sophia’s wedding ring:

Man’s accidents are God’s purposes

Sophia A. Hawthorne, 1843

Nath’l Hawthorne

This is his study

1843

The smallest twig

leans clear against the sky.

Composed by my wife,

and written with her dia-

mond

Inscribed by my

husband at sunset,

April 3, 1843.

on the gold light—SAH

38.

Hawthorne’s travelogue hints at something illicit in the love between Byron and his half-sister. “One of the stems still lives and flourishes,” he writes, “but that on which he carved the two names is quite dead, as if there had been something fatal in the inscription that has made it forever famous.”

39.

Or maybe graffiti is defined not by its context, but by the wrong context. Something other than where it belongs.

40.

In 2005, Banksy smuggled a fake piece of cave art into the British Museum. Early Man Goes to Market depicts a stick figure pushing a shopping cart in pursuit of a wildebeest. His work hung on the wall for three days before it was spotted by curators.

41.

Perhaps the privacy of the stall, the anonymity of the wall, breeds a certain bravado. Today internet forums are our equivalent. One hopes future generations will not judge us.

42.

In the basilica, Pompeii: Virgula to her friend Tertius: you are disgusting!

43.

The fact that graffiti is practiced incognito makes it particularly attractive to the subversive, the revolutionary, the underground. French artist Thierry Noir painted the Berlin Wall illegally every day for five years. He said, “if you paint on the street you are immediately political, because you change the life of the people.”

44.

But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling, like dew, upon a thought produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions think.

–Lord Byron, “Don Juan”

45.

Byron’s revolutionary spirit manifested itself early. According to another Harrow legend, when a new headmaster was appointed against popular student opinion, Byron led a revolt that culminated in plans to assassinate the new arrival.

The scheme, which would go down in school history as the Gunpowder Plot, was only aborted on Byron’s insistence that the names carved into classroom walls be preserved for posterity.

46.

In one of Banksy’s most famous murals, Power Washer, a maintenance worker pressure-washes art off a wall. The art he is defacing appears to be ancient cave paintings.

47.

“Imagine a city where graffiti wasn’t illegal . . . Where every street was awash with a million colors and little phrases. Where standing at a bus stop was never boring. A city that felt like a party where everyone was invited . . . imagine a city like that and stop leaning against the wall—it’s wet” (Banksy, Wall and Piece).

48.

In the early hours of September 15th, 1983, New York City police arrested a black graffiti artist for writing on a subway wall with a felt-tip marker. Later that morning they would deliver him to the hospital in a coma. Michael Stewart died within two weeks, never having woken.

Basquiat depicted the incident in a mural. Two ghoulish policemen stand over their victim with nightsticks raised. Hovering between them, Stewart’s face is a blank silhouette, making it clear that when Basquiat wrote ¿DEFACIMENTO? next to the image, he was not talking about the wall.

49.

Now we can imagine our own victims into the picture.

50.

Noir painted the west side of the Berlin Wall until one night in 1989, when he darted through swiftly appearing gaps to paint the other side.

As the holes in the wall grew larger, Noir did not grieve the destruction of his five years’ work. “I was not crying because my world was pulled down,” he claimed, “it would be arrogant to say that. It was not an art project, it was a deadly border.”

51.

“A wall is a very big weapon” (Banksy).

52.

We still don’t know who Banksy is.

53.

After carving his name in the dungeon of Chillon, Byron returned to his lodgings and wrote a poem. That summer of 1816 would be a productive one for Byron and his traveling companions, who collectively composed Frankenstein (Mary Shelley), “Hymn to intellectual Beauty” (Percy Shelley), “Vampyre” (an obscure poem by Byron’s doctor that would later inspire Bram Stoker), and “The Prisoner of Chillon” (Byron).

54.

Perhaps when he carved his name at Chillon, Byron was simply testing which would outlive the other: poem, or stone?

55.

Consider the context. If this was about ego, why a dark dungeon? Prison walls are where the incarcerated tally days.

56.

It might be months, or years, or days,

I kept no count—I took no note,

I had no hope my eyes to raise.

–Lord Byron, “The Prisoner of Chillon”

57.

In 2018, Banksy installed a 70-foot mural in downtown Manhattan protesting the imprisonment of Turkish-Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan. The work consists of tally marks representing Doğan’s days in jail. Doğan appears behind one of these “cells,” her hand gripping what is at once a bar, a pencil, and another lost day.

58.

In his poem, Byron’s prisoner of Chillon is a man held captive for defending his religious beliefs. Chained to a pillar alongside his brothers, who slowly waste away, the hero is left to listen to the waves of Lake Geneva lapping at the walls.

59.

Whether the real prisoner of Chillon, François Bonivard, was as romantic a figure as Byron suggests is called into question by many historians.

60.

Bonivard was known as an unruly prior who joined the Children of Geneva, a group of Protestant revolutionaries opposing the rule of the Catholic Duke of Savoy. One night, hearing of the duke’s approach, Bonivard fled Geneva dressed in the costume of a monk, only to be betrayed by the real monk who’d promised to hide him.

61.

Before his imprisonment, Bonivard was perpetually in debt due to extravagant living—he liked to throw a good party. His neighbors were so scandalized by this that, after the death of his first and second wives, they forced him to marry his third for propriety’s sake and, when she died, a fourth.

62.

Byron’s fêtes at the estate he’d inherited from his uncle were infamous for his wild antics—like inviting guests to drink from a skull he’d found in the crypt, while dressed in the costume of a monk.

63.

Fifteen years prior to Bonivard’s capture by the Duke of Savoy, Martin Luther marched on Wittenberg and nailed his 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church, sparking the Reformation that divided Catholics and Protestants, and eventually led to Bonivard’s imprisonment at Chillon.

64.

Of course, whether Luther actually nailed his proclamations to the church door is contested by many scholars.

65.

Leaving us to wonder: would his words have carried more weight had Luther etched them onto the door?

66.

God knew this. See: the Ten Commandments.

67.

When Bonivard was finally freed from Chillon by the Bernese in 1536, he was given a hero’s welcome back in Geneva. To many, he was a martyr of the Protestant faith.

During Bonivard’s captivity, however, Geneva had reformed beyond his moral compass. The city’s elders began to keep a close eye on him; again and again Bonivard’s frolicsome behavior was reprimanded by the order he’d helped to establish.

68.

While he was their romantic poet-hero, English society tacitly agreed to overlook Byron’s excesses. But as rumors of sodomy circulated, the notoriety Byron had earned through his verse quickly waned.

“I was advised not to go to the theaters, lest I should be hissed, nor to my duty in parliament, lest I should be insulted,” writes Byron of his last days in England before fleeing to the continent. “Even on the day of my departure my most intimate friend told me afterwards that he was under apprehension of violence from the people.”

69.

John Calvin arrived in Geneva the year Bonivard was released from prison. In the records of the censorship committee Calvin established, Bonivard’s name appears with alarming frequency. He is charged with everything from patronizing the wine shop to playing backgammon to “wearing a bouquet on the ear,” which, the record states somewhat unfairly, “ill befits him—an old man.”

70.

Even as he withdrew to the shelter of the Swiss Alps, Byron was under the constant surveillance of prying English tourists. One enterprising hotelier rented telescopes that could be trained across Lake Geneva to where Byron’s laundry might be examined for women’s garments.

71.

Eventually, the vigilance of the Swiss ended in tragedy. Bonivard’s fourth wife, a defrocked nun, was accused of infidelity. Though Bonivard tried to save her, she was sewn into a sack and drowned in the Rhône.

72.

“The greatest crimes in the world are not committed by people breaking the rules but by people following the rules. It’s people who follow orders that drop bombs and massacre villages” (Banksy, Wall and Piece).

73.

In the case of Michael Stewart, the police were acquitted. The all-white jury reached their verdict after deliberating for six days less than it took their victim to die.

74.

“Must crimes be punish’d but by other crimes, and greater criminals?” (Lord Byron, “Manfred”).

75.

When Byron scratched his name into that pillar, perhaps he was already imagining his character, the accused, chafing within the narrow circumference of his bonds.

Remember: at the time of composition, Byron had just been exiled from England after a messy separation from his much-pitied wife, trailing a string of accusations that included sodomy—punishable by imprisonment—and incest with his half-sister Augusta.

76.

“It could have been me. it could have been me” (Basquiat, on the death of Michael Stewart).

77.

“The commandant thrust me into a dungeon, the bottom of which was deeper than the lake upon which Chillon is situated, where I lived for four years, and had so much leisure for walking to and fro that I imprinted a little path in the rock, which was the pavement there, as though one had done it with a hammer” (François Bonivard).

78.

“The names are still very legible, although the letters had been closed up by the growth of the bark before the tree died. They must have been deeply cut at first” (Nathaniel Hawthorne, on the tree in Byron’s garden).

79.

We don’t know how much context Byron would have known about Bonivard upon his visit to Chillon. “When this poem was composed,” Byron admits in a note, “I was not sufficiently aware of the history of Bonivard.”

Yet when he saw the tread of Bonivard’s footprints against the prison pavement, Byron carved his own name into the encircled pillar.

80.

“It was a way for me to show people that this mythical wall was not built for ever and could be changed” (Thierry Noir).

81.

“I am so changeable, being everything by turns and nothing long—I am such a strange mélange of good and evil, that it would be difficult to describe me” (Lord Byron).

82.

Empathy, of course, is the opposite of ego, and something more like love.

From the Greek empatheia: literally, “passion.”

83.

While Byron had been enamored by Greece during his early travels, he did not meet the oracle at Delphi. If he had, she might have warned him not to return.

84.

“Underlying Jean-Michel Basquiat’s sense of himself as an artist was his innate capacity to function as something like an oracle, distilling his perceptions of the outside world down to their essence and, in turn, projecting them outward through his creative acts” (Fred Hoffman, “The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works”).

85.

Writing on a wall often carries the mythological weight of prophecy. As in the commonplace idiom, “the writing is on the wall,” meaning: your fate is sealed.

86.

Fifteen years after carving his name on one of the country’s ancient pillars, Byron would die in Greece while fighting with insurgents to free the country from Ottoman rule. He was 36.

87.

When Alfred Tennyson, an adolescent at the time, heard the news of his hero’s death, he went out into the woods, threw himself on the ground, and carved the words Byron is dead into a rock.

88.

To mark the spot where earth to earth returns!

No lengthen’d scroll, no praise

encumber’d stone;

My epitaph shall be my name alone.

–Lord Byron, “A Fragment”

89.

Near the Vesuvius Gate, Pompeii: Marcus loves Spendusa.

90.

Some mistakes are corrected by history.

91.

Luther’s lack of foresight was rectified almost 400 years later. The Castle Church was fitted with bronze doors weighing 2,200 pounds, and engraved with his 95 theses.

92.

And sometimes, words must cover our wounds.

93.

Chillon! thy prison is a holy place,

And thy sad floor an altar—for ’twas trod,

Until his very steps have left a trace

Worn, as if thy cold pavement were a sod,

By Bonivard!

–Lord Byron, “The Prisoner of Chillon”

94.

At times, it takes defacement to see our own face. To recognize that we are all mere scratches. Something other than where we belong.

95.

Byron saw a prisoner at Chillon and wrote his name to set him free.

__________________________________

From AGNI 90, under the title “Byron Was Here.” Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2019 by Jodie Noel Vinson.